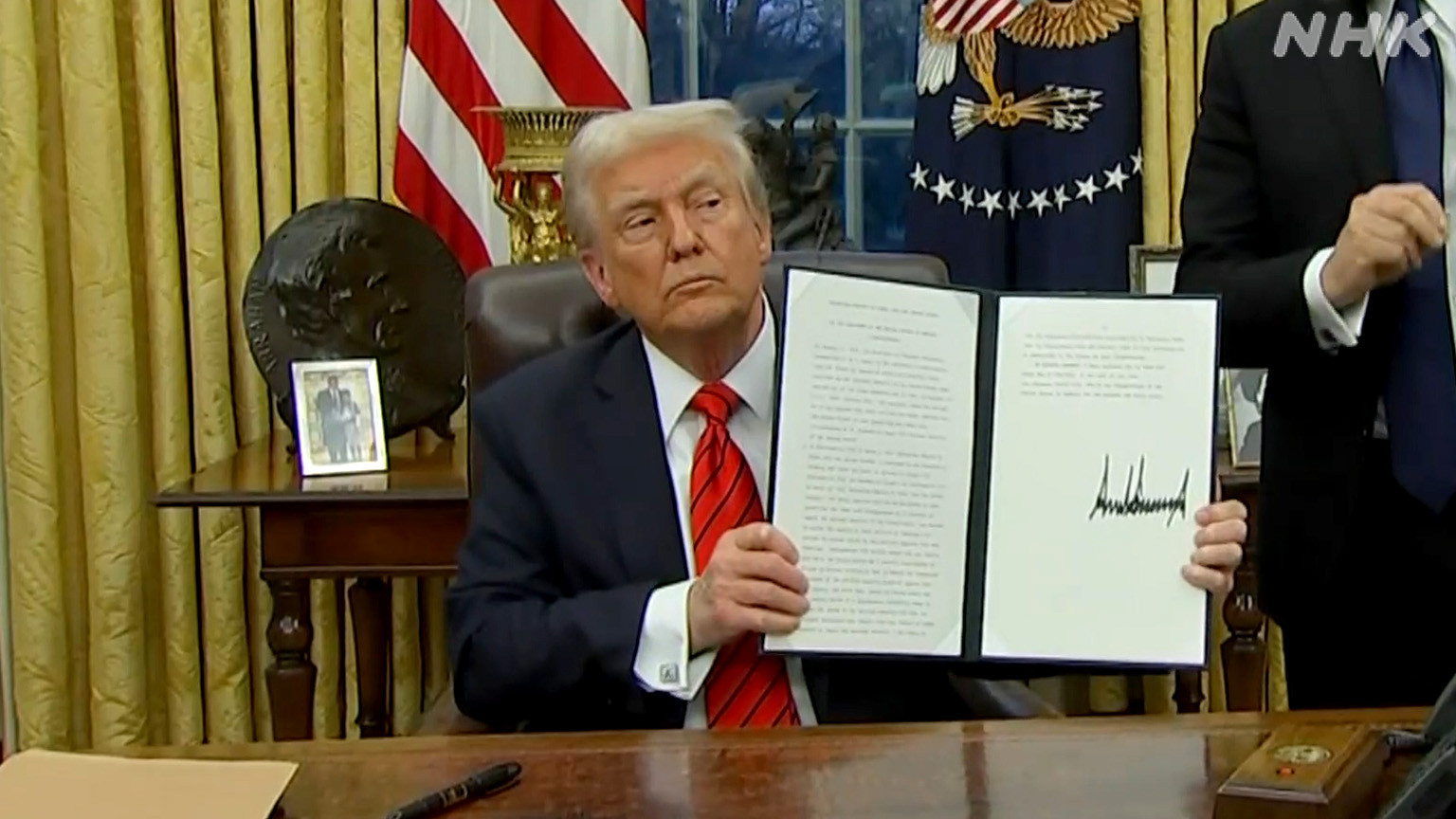

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s statement on revising India’s No First Use nuclear policy in the future is open to interpretation

The Indian Defence Minister’s recent statement, anticipating a possible change in India’s nuclear policy in the future, is open to interpretation, and what it means for its nuclear doctrine in coming times is contingent on how the contours of India’s conventional escalation with its neighbour Pakistan shapes up.

The statement by Rajnath Singh signals a facile if not deep thought within the Narendra Modi Government for some time now on the need to revise India’s No First Use (NFU) policy, especially when seen as a corollary to the former Defence Minister, the late Manohar Parrikar’s statement in 2016 about being open to revision of India’s NFU policy.

Rajnath Singh’s recent statement on NFU seems only a step forward, as unlike previously, it does not come with “personal opinion” caveat.

India first adopted a NFU policy after its second nuclear tests at Pokhran in 1998. Soon after, in August 1999, the Indian government released a draft of the doctrine which asserts that nuclear weapons were solely for deterrence and that India would as a nation pursue a policy of “retaliation only.”

The document also maintains that India “will not be the first to initiate a nuclear first strike, but will respond with punitive retaliation should deterrence fail” and that decisions to authorise the use of nuclear weapons would be made by the Prime Minister or his ‘designated successor(s)’.

That the Defence Minister’s NFU comment came in Pokhran, the site of the 1998 nuclear tests, gives wings to speculation. It also comes days within the Modi Government’s decision to change the status of Jammu and Kashmir, but most noticeably, amidst an ongoing diplomatic and cross-border escalation with Pakistan.

If this is any indication, it shows that the rungs of conventional escalation between India and Pakistan may be reaching the fag end, and the Indian government wants to come out of the retaliation-counter-retaliation cycle with a conventionally inferior power, which is on a quest to gain conventional parity with India. Pakistan’s constant threat of battlefield nuclear weapons further complicates India’s conventional superiority gap assessment vis-à-vis Pakistan, setting foundations of a strategically revisionist thought process within India.

Chances of nuclear policy revision seem more plausible in the light of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) historical assessments about making India a credible nuclear power through a directly proportional relationship between the country’s political will to revise its nuclear policy and deterrence-based posturing.

The Vajpayee Government’s decision to conduct the 1998 nuclear tests and project India as a credible nuclear power is a case in point. The Pokhran link to Rajnath Singh’s comments further underpins this government’s conviction about the aforementioned proportionality.

The Defence Minister’s assertion has reignited the debate on the need for India’s nuclear policy revision but whether it means that India is ready for a change in its NFU policy and will move to a First Use (FU) strategy is debatable.

Currently, there are various technological and financial constraints for New Delhi in erecting an effective first strike capability against Pakistan or China. A credible FU nuclear strike capability, before anything, would require significant investments in Command, Control, Communications, Computer, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) and Target Acquisition (TA) capabilities. The essence of FU strike capability is pre-emption and accuracy, and would require an unfailing intelligence and shorter time-gap in the readiness sequence: passing of intelligence, civil-military decision-making, mating weapons with warheads, leading to final pre-empting strike on the enemy.

India’s first strike aspirations also face structural constraints, particularly apropos the decision-making paradigm that exists as of now. The civil-military gap in India’s strategic forces decision-making is deliberately made to create a non-provocative yet punitively reassuring second strike stance towards the enemy and, most importantly, to avert any rash decision leading to catastrophe. Such a doctrinal posture makes a lot of sense when viewed in the light of India’s non-alignment past, but is increasingly losing currency in the eyes of a revisionist government and a rallying nation.

India’s current civil-military gap is ideal for a country with a NFU policy. It’s a purposeful decoupling to mandate civilian supremacy in strategic decision-making and create checks and balances. In direct contrast to this, the FU force structure would possibly require an ever-vigilant and ready strategic posture with quick and decisive calls for action when needed, which in turn would need a smaller gap between the civilian go-ahead and the military’s final call, leading to the targeting and firing of the weapons with nuclear warheads.

New Delhi’s lessening of the civil-military gap can be seen in the context of the government’s recent decision to appoint a Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), a five-star General with possibly a Cabinet rank whose role would supersede the three armed forces chiefs.

The centralization of power through the office of the CDS will not only consolidate general decision-making in one office, but is likely to reduce intra-forces rivalry on issues of budget and government favourability between the three wings of the armed forces.

In the strategic context and in relation to the country’s nuclear force posture, the office of the CDS is likely to be more in tune with its FU strategy than it will be with its current NFU strategy. As such, the Defence Minister’s statement hinting at a possible revision of India’s nuclear strategy could also be seen in the context of India’s decision to appoint a CDS.

While it is unlikely that India will go for a doctrinal alteration anytime soon, it could serve as an extremely potent plank to fight the next general elections in 2024. Given the kind of investments needed for readying a FU force structure, a revision anytime soon will be difficult.

However, to the extent that deterrence behavior in nuclear states is as much psychologically induced as it is from concrete, stated and factored capabilities, the Defence Minister’s statement has caused visible concerns in Pakistan.

Locating India’s overall NFU strategy, its force posture towards hostile neighbours, the number of warheads and the escalatory potential in a comparative context, paints a picture of a benign nuclear giant.

Doing away with NFU will repaint this picture, besides possibly affecting stability in the region.

That is a price this government is considering to pay in the light of New Delhi’s increasing fatigue with a rapidly lessening conventional gap with Pakistan, especially with Pakistan’s increasing tendency to factor Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNW) within conventional escalation spectrum, and with the solidifying China-Pakistan axis.

If Balakot lowered the threshold for India’s conventional response to Pakistan and altered the nature of response, a doctrinal shift from NFU to FU might go a long way in ushering an altered deterrence-induced behaviour in Pakistan, hopefully leading to a better future for bilateral ties between India and Pakistan.

(The writer is Visiting Fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington D.C & Deputy Director Kalinga Institute for Indo-Pacific Studies)

Writer: Vivek Mishra

Courtesy: The Pioneer

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)