Proscribing on the basis of immorality, just because something might have offended an individual or community, has little to do with preserving the moral fibre of a nation

In 1973, an Urdu film, Insaan Aur Gadha, was suddenly ordered by the Government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to be taken off the screens, just weeks after it was released in cinemas in Pakistan. Directed by the late actor and director, Syed Kamal, the film was a satire on the condition of people in Pakistan. Popular actor and comedian Rangeela played the role of a donkey who had turned into a person after praying to God to transform him into a human being.

In a biting reflection on the state of affairs in Pakistan, after the donkey’s prayers are answered and he turns into a man, he soon realises that his existential purpose and sense of morality had more meaning, balance and clarity as an animal than as a person. Disappointed by humanity (or its lack thereof) he ends up asking God to turn him back into a donkey.

The reason the movie got taken down by the Government was a scene in which the donkey-turned-man addresses a large gathering of donkeys. He promises them that he would fight for their rights and against their cruel and unjust human masters. The late filmmaker, Mushtaq Gazdar, in his book Pakistani Cinema: 1947-1997, writes that the scene did not hide the fact that it was parodying Prime Minister Bhutto’s signature style of populist oratory. This was what had angered him. But his Government’s censor board shared this reservation only with the producers of the film. Publicly, the reason given for the ban was that the scene had ridiculed the masses by depicting them as a bunch of donkeys.

Even though the movie was eventually allowed to return to the cinemas, it is interesting to note the nature of the justification given by an offended Government for its removal from the country’s cinemas.

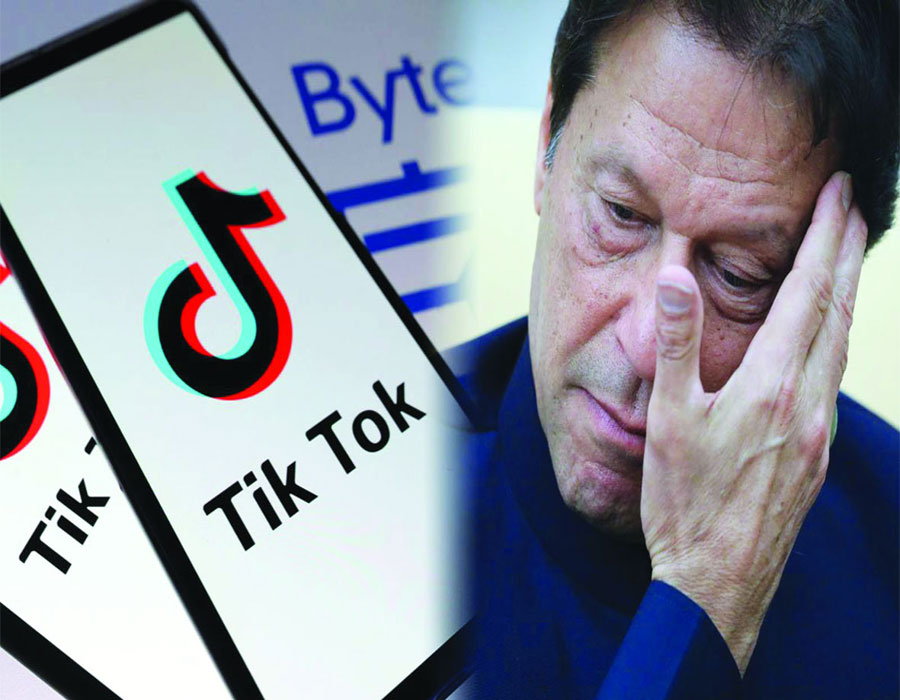

Recently, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) banned the popular Chinese app Tik Tok just days after Prime Minister Imran Khan lamented that it was promoting “immorality” in the country. However, in a tweet, the senior political commentator Najam Sethi insisted that the app was banned because many of its local content-makers were parodying and satirising Khan’s populist rhetoric, which is in stark contrast to his Government’s political and economic incompetencies.

The ploy of using moral or religious rationale and angles to ban a popular cultural product that has offended a sitting ruler’s inflated ego was not present in the country before the late 1970s. Had it been in use before that, the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto regime would not have hesitated to use it to ban Insaan Aur Gadha. Or for that matter, the Ayub Khan regime would have used it to outlaw 1959’s Jago Hua Savera.

Jago Hua Savera, scripted by the famous communist poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, is a story based on the struggles of a poor fishing village in former East Pakistan. Ayub saw it as commentary against his ambitious economic plans. But the reason given by the regime for banning it was that its content was “inflammatory” and that it could arouse hatred among East Pakistan’s Bengali majority against their West Pakistani brethren. In today’s Pakistan, Ayub could have simply banned it on the grounds of it being a communist film, and thus promoting atheistic ideas. In his 1967 book, Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan, the scholar Aziz Ahmad writes that the founders of Pakistan went out of their way to underline the fact that their idea of Islam was different to the one held by most ulema (Muslim scholars) and clerics. To the founders, their idea of Islam was inherently modern, rational, sophisticated and progressive, as opposed to the “reactionary” and myopic ideas of the faith propagated by the Islamists.

The State and various governments carried forth and further expanded this narrative till 1974. Therefore, till then, the notion of banning a cultural product on the basis of morality would have seemed contrary to this narrative or something that was the domain of unsophisticated mullahs.

However, things began to change rapidly after the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto regime handed the once-despised “forces of myopia” their greatest victory through the constitutional Second Amendment in 1974, which ousted the Ahmadiyya community from the fold of Islam.

Bhutto believed that he was ahead of the curve by noticing the rising interest in the Muslim world towards (albeit utopian) ideas of “Islamic rule.” The French political scientist, Oliver Roy, in his 1992 book, The Failure of Political Islam, agrees that indeed from the mid-1970s, polities in the Muslim world had begun to shift rightwards towards political Islam.

But Bhutto was giving himself too much credit for anticipating this shift, and, more so, for believing that he was monopolising it before the Islamic parties could. Because no matter how hard he tried, the Islamic parties understood the dynamics of this better than he did and were, therefore, more adept at exploiting its emotional and psychological appeal, as they did during their 1977 protest movement against the Bhutto regime.

The tactic of using the Islamic or morality card to proscribe a cultural product which, in reality, has only offended the ego of a ruler, earnestly began from 1977 onwards, with the coming to power of the reactionary Zia-ul-Haq dictatorship.

Before my father passed away in October 2009, he would often tell his friends the story of how, soon after the 1977 coup, when he was a reporter at a large Urdu daily, he was told that his name had been put by the dictatorship on a “blacklist” of “pro-Bhutto journalists.” This meant he could not write anything on politics. So, a few days before 1978’s Eid-ul-Aza — the day when Muslims sacrifice bulls, goats or camels — my father was allowed by the editor to do a completely apolitical piece on a makeshift market of sacrificial animals in Karachi’s Gizri area. He went there, completed his report and submitted it.

The next day he was told that the report had been removed by the Zia regime’s Information Ministry, which used to scan newspapers before they went into print. A member of the ministry told the editor that there was a whole paragraph in the report about how people were checking the front teeth of the sacrificial goats. The Ministry man then added that the writer was being “cheeky” by indirectly mocking Zia’s prominent front teeth. But the reason provided to my father was that the article was “ridiculing the holy tradition of animal sacrifice.”

The act of proscribing a cultural product on the basis of immorality just because it offends the bloated ego of an individual or that of a community has little or nothing to do with preserving the moral fibre of a nation.

The ban culture is all about feeling a sense of power, which feeds inflated egos, and the monomania of those who have an entirely illusionary understanding of the society they live in. Unlike those who go on a banning spree to avenge what they believe has offended them individually, the other lot actually believes they are fighting a holy war to save society.

The result is a suffocating environment, which stunts the growth of creativity, tolerance and of democratic values in a society. This is what is happening increasingly in Pakistan and around the world, especially where populist or Right-wing regimes are in power. This must be stopped at all cost before we all lose our freedom of speech, creativity, innovation and thought. That will be a downright tragedy of epic proportions.

(Courtesy: Dawn)

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)