If impersonating was Jessica Krug’s way of legitimising herself as an academic, mobilising the disenfranchised and then representing them as perpetual victims is another

The recent confession of Professor Jessica Krug about her true identity may have outraged many. However, it offers an opportunity to re-evaluate what academics given to consciousness-raising often do. Krug, a historian teaching African history at George Washington University, admitted in a blog that she is a Jew born of White parents and has nothing to do with African-American Blackness, something which she had been claiming for a long time. She regretted that her action was “the very epitome of violence, of thievery and appropriation, of the myriad ways in which non-Black people continue to use and abuse Black identities and cultures.” In the same breath, Krug declared that she is no culture vulture but a culture leech. Her actions though have proved otherwise. Prior to her outing of herself in the blog, Krug had used a more African-sounding name (Jessica La Bombalera) in her activist avatar, and during a demonstration had questioned the gentrification of New York by calling out the “White New Yorkers” for having failed to spare a thought for Black and Brown New Yorkers. We don’t know what prompted her to come out as White though it is said that there were increasing murmurs about her identity that forced her to do so.

The knowledge market: On the face of it, a situation such as this is not representative of the academic environment in the US or India. This is where the present intervention marks its departure. Krug’s admission, no doubt, betrays her inability to fake it any longer, but more importantly, it reveals the malaise of contemporary academic knowledge production. The difference between usurping the voice of the weak (what academics do) and pretending to be the weak (what Krug did) is perhaps one of degree and not of kind. When Krug claimed to be a culture leech rather than a vulture, she was highlighting that subtle difference. We can be reasonably sure that Krug is not the first one and won’t be the last, at least until the academic market stops converting experience of marginality to elitist knowledge and suspends placing a premium on the dish of victimhood.

Those who see Krug’s problem as an individual transgression are either oblivious of what goes in the name of knowledge or are beneficiaries of such methods. Academic scholarship has often been obsessed with not just representing cultural difference but also in producing, controlling and owning it. Few questions are raised about the moral foundation of such knowledge. It is taken for granted that if cultural difference does not exist, it is to be invented and if academic knowledge has to sustain itself, “savage slots” are to be continuously filled. Krug took it one step further. Instead of being content with immersion or academic self-othering, or sponging on cultural difference of the Blacks like a leech, she chose to become indistinguishable from what she was writing about.

A few years ago, Harvard University had gone to the market advertising its culture of diversity by projecting Elizabeth Warren, a law professor who claimed to be a Cherokee Indian (and went on to have a thriving political career). The difference between birth identity and assumed identity may appear as academically adventurous and a cool way of moving beyond fixed identities, but in reality, and for the people whose identity is thus stolen, it is an act of violence. In a post-modern academic world, race is increasingly seen as a political invention rather than a frozen identity, thus creating a pathway for becoming someone else, or belonging without believing. That way, what Krug did was chic because she was making herself a trans-individual. But we all understand that Blackness as knowledge and Blackness as experience (not just individual but collective and communal) are different things. One is of romanticisation, appropriation, exoticisation, even silencing, and the other of everyday-ness and its struggle.

Though living the marginal life involves costs in real life — humiliation, powerlessness, sub-human life and so on — the academic world knows the benefits of being Black or minority, at least in the latter’s potential for being objects of knowledge. In the market of scholarship, victimhood sells and is safely monetised: Black or Coloured in America and Muslim or Dalit in India. Cultural difference and victimhood are a minefield of fame and money.

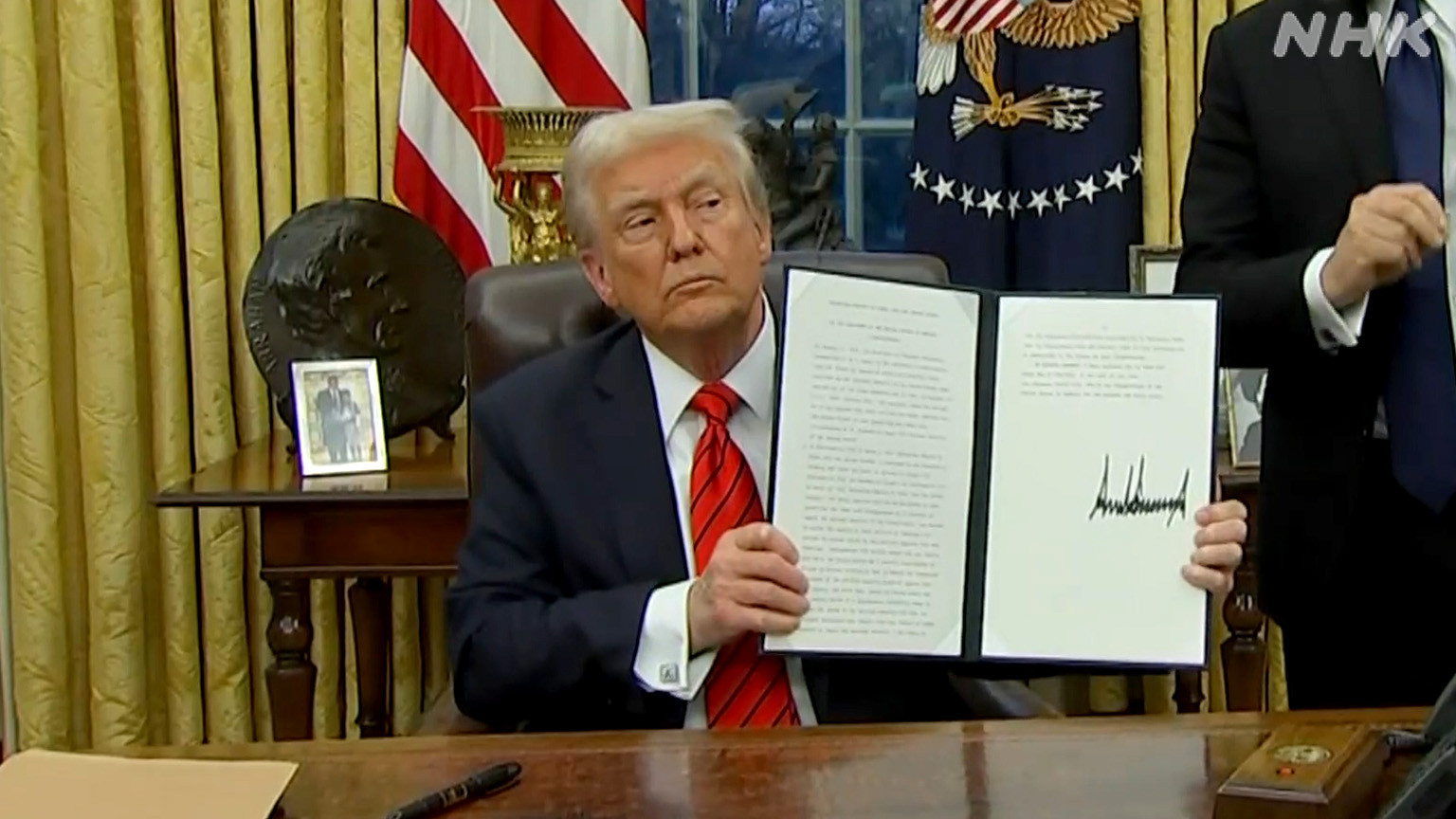

That said, the demonstrations over the death of George Floyd or over atrocities against Dalits reveal a mindset of remembering the victim only when they can be used as a medium of accumulating symbolic capital. It is not just about dehumanising and instrumentalising them for advancing one’s career but also the belief that being a victim pays. The willingness to barter away one’s identity, as Krug did, springs from the conviction that academic benefit from such impersonation outweighs the losses.

Imaginary victims: What Krug did not acknowledge in her confession is that her violence was not only directed as genuine Black experience but also at White experience. While faking to be Black, she was creating a template in which Whiteness is antagonistic to Blackness and so was perpetuating a race binary. She was reducing her own race by making it appear inflexible, intolerant, exclusivist and the negation of Black experience. Her impersonation implied that sincere appreciation of Black history is not possible while being White. She also pandered to those radical elements who believe that genuine understanding of the other is possible only by denying one’s own authenticity. Her pretension perpetuated the academic world of make-believe that being majority is a matter of shame and its disavowal or degradation is necessary to speak for the weak.

Krug converted the Black experience to some bare codes defining Black authenticity: Angry, violent, abusive. That is what she was doing while appearing as Jessica La Bombalera. The resonance of this mentality in India is not difficult to find. Dalits and Muslims are often projected in the media as angry and violent because that is the only way to be weak and a minority. Being helpless and being violent are the expressions of the same authentic core. Academics like Krug not only stereotype or steal identity, they also create norms which guide victimhood. As long as the Black man is anti-police or a Muslim is anti-State or a Dalit is anti-Brahmin, they are authentic; a republican African-American is beyond this template as is a nationalist Indian Muslim.

An academic from Hunter College named Yarimar Bonilla said something very revealing about Krug, that the latter not only fooled others about being a woman of colour, but also into thinking that they are actually inferior, intellectually and politically. Krug was denying them their being, their worth outside her own writings and activism. What it reveals is that being a victim of violence has more moral, academic and perhaps political worth than being normal and majority.

So behind minority identity, its production and circulation, there is a political economy of cultural difference and of diversity that can be a passport to capital — economic or symbolic. Becoming the other involves a life-time of dedication to live another life. Krug must have internalised the new identity. In the acknowledgment section of her book Fugitive Modernities, she thanked her “ancestors, unknown, unnamed, who bled life into a future they had no reason to believe could or should exist. … Those whose names I cannot say for their own safety, whether in my barrio, in Angola, or in Brazil.” It may be mentioned here that Krug had received financial assistance for writing this book from Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

It is not important to know whether being White or feigning Blackness is better for being a scholar of African history. What is important is the knowledge itself — of victims and minority. As long as we are getting ethnic food in Delhi haat (market), it does not matter if the cook is White or Brown. There may be many service providers but the good/service is the same.

Impersonation as passport: If impersonating was Krug’s way of legitimising herself as an academic, making common cause with a supposedly discriminating law or mobilising the disenfranchised and then representing them as perpetual victims is another. The latter is much more rampant and a fairly common practice governing funding agencies that guide research on minority cultures. Though such politically engaged research may appear as a fight for an inclusive polity, it also betrays the desire to be the source of all cultural politics.

That partly explains Brahmin academics monopolising Dalit experiences. At a poetry reading session, a very fair-skinned Brahmin poet advocated “our own” Dravidian cause and how her Dravidian skin will always be a marker of her identity. She spoke with a flair even as her complexion struggled to adjust itself to the victim narrative. Playing around this politics of “we” and trying too hard to be someone else in order to be legitimised is an effort complementary to Krug’s.

(The writer is Professor, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Madras and a cultural critic.)

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)