Beijing’s decision to remove the two-term limit for the Chinese president shows their contempt for the Western liberal democracy “facade”

The amendments to the Chinese Constitution raised to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, removing the formal two-term limit to presidential appointments, marked a welcome step in striving towards a vision of a society and internationalism governed by the principles rooted in communal harmony. This is happening at a time when the Western democracy, since a long time has been degenerated into a carefully managed puppet of the big capital, punctuated by periodic elections every few years which give the people the illusion of the exercise of political power.

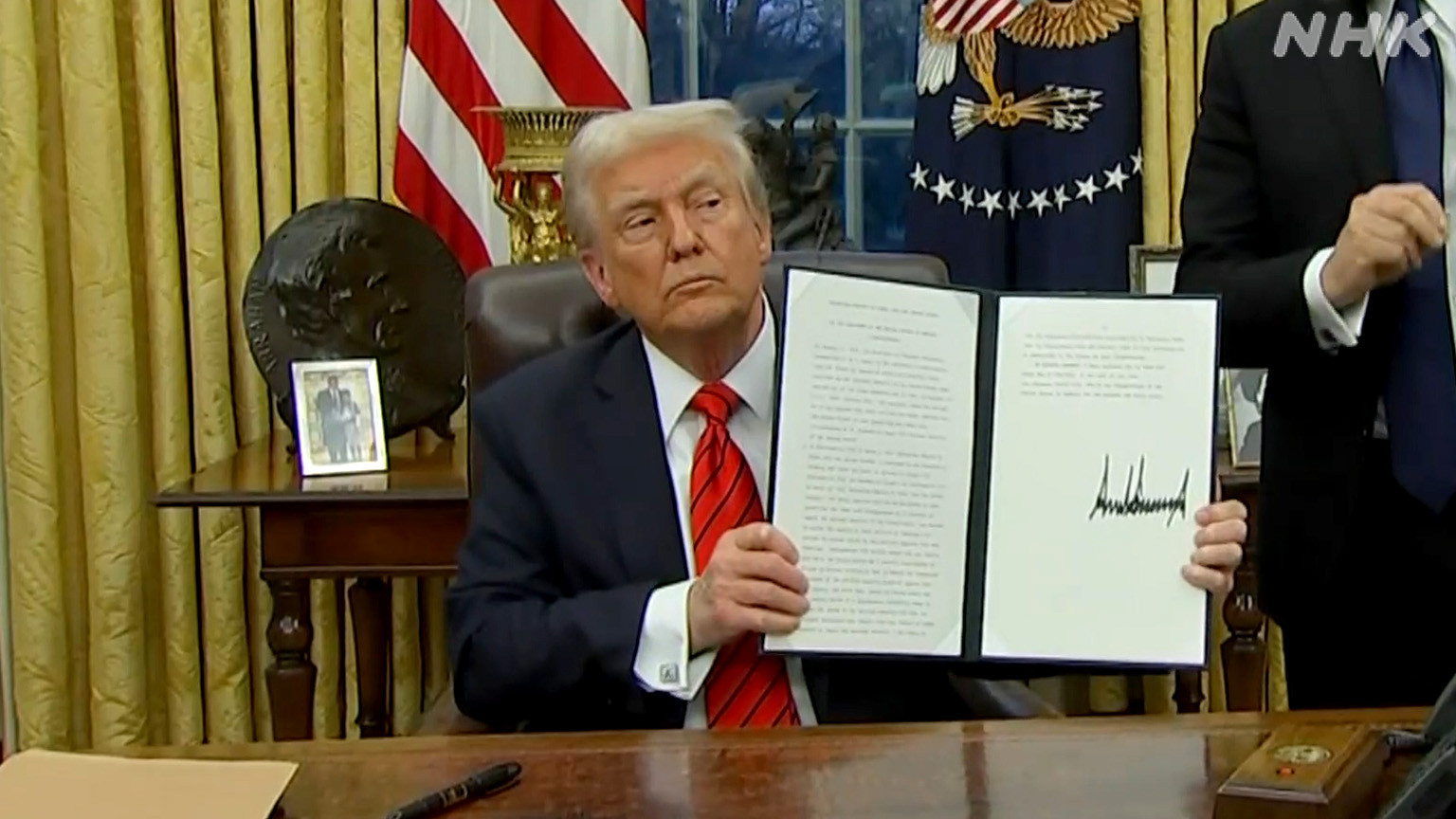

The election of Donald Trump in the US, the popularity of Putin in Russia, the resurgence of the BJP across India, the resurgence of French people led by a President who has taken the entrenched lethargic socialist interests head-on, and, now the overwhelming support for instituting back the ‘President for life’ system in China, show that the people world-over are revolting against the carefully managed façade of Western liberal democracy.

The Chinese have been accustomed to the idea of ‘President for life’, first, in the form of monarchical rule and then during the years of Mao Zedong. It was only after 1976 that Mao’s liberal successor, Deng Xiaoping, along with several other changes to usher in the capitalist economy in China, did away with the ‘President for life’ policy and, instead, introduced formal two-term limit to the re-election of the President. But because the Communist Party of China (CPC), along with the Central Military Commission (CMC), continued to reign supremely over the Chinese polity and foreign and defence affairs, the institution of the two-term limit could not mean much. The removal of the two-term Presidential election limit is just a formal change, as Xi Jinping was already the leader of the CPC and the CMC — two most powerful institutions in Chinese polity — and they, in any case, have no term limits. So, Xi would have continued to hold sway well into the future, with or without this small formal change. But with the removal of the term-limit, the emergence of an unnecessary parallel power centre is precluded and a smooth functioning of the domestic and foreign affairs can take place.

For apologists of the two-term limit, at best, such a limit could inspire competitive politics within the CPC for higher positions — but this intra-party politics is hardly ‘democratic’ politics. It is quite the contrary, in fact. Intra-party competition within CPC — without there being any political parties in the public arena and no typical elections, gave rise to a corrupt system based on politics of patronage, where individual members and those belonging to powerful and wealthy families could try to take advantage by lobbying those at the top or themselves harbor ambitions to rule the country.

All the while, this unhealthy competition remained confined within the CPC, thereby giving rise to a privileged corrupt class of Chinese ‘princelings’ against whom even public revolts had started a few years back. How such a system could be called ‘democratic’ in even the remotest sense of the word is baffling. To put it mildly, one wonders why, then, critics are decrying the passage of such a system, which was ushered in when Xi Jinping assumed power. With Xi’s ascendance to power, one of the most palpable first actions was, precisely, to root out this entrenched corruption from the system. Obviously, the international media — with Indian media parroting their international counterparts — liked to term this as suppression of ‘political dissent’ and suppression of anyone who could pose a threat to Xi. But these remain mere speculations in an age where ‘dissent’ itself has become a manufactured and sponsored process — like how the West commonly funds ‘democratic dissent’ in various parts of the world to overthrow recalcitrant regimes.

In the Chinese case of the rise of Xi, the suppression of dissent theory does not hold because his measures, his re-election and the imprinting of his thought on socialism have had widespread support in the party and the Government as well as in the public. The only few dissenting voices are limited to Western-educated or Western-backed Chinese living in the USA — their numbers as well as their location rendering their voices largely irrelevant.

The democracy they seem to be trying to usher in in China — at a time when the West is failing — has never even existed in the one-party system of China, as economic capitalism never gave way to political capitalism. The tightly-knit political system, especially under Xi, became an instrument for the revival of traditional Chinese values and a threat to the onslaught of Semitic religions, which had gained a substantial foothold in China.

Much like the crusade against the corrupt elite of China, it was, again, under Xi’s leadership that the voices of the Confucian scholars began to be heard seriously by the Government. For more than a decade, they had been lamenting the ‘Western cultural invasion’ of China, but it was only under Xi that the Government displayed the gumption to officially adopt the policy of recognizing this cultural invasion and fight it by a policy of national cultural revival, aligned with the principles of Xi’s ideas of socialism.

This staunch nationalism, under which Xi is uniting the CPC, the CMC and the entire nation, is one of the reasons for the rise of China and the public popularity of Xi. As for the questions of democracy and socialism, it must be emphasised that the present spirit of Chinese socialism (and not Communism) is not at all the regimented and selfish economic socialism of the West. The effort in Asia has always been towards a spirit of socialism grounded in spiritual harmony — China, under Xi, is consciously trying to move towards that.

The assertion that this Asiatic idea of polity would degenerate into dictatorship is problematic. Only regimented systems, arising out of the material-vital spirit to cater to the selfish interests of a utilitarian and commercialized society (be it communism or capitalism or socialism), can so degenerate into dictatorships. Dictatorships are a very common modern phenomenon — a result of democratic revolt itself. Almost all anti-colonial nationalist movements, spanning Asia, Africa and the Middle east, were born out of a discourse of rights, democracy and equality — India’s Nehru was a leader and product of that age. Yet, except for India, almost all these democratic struggles — including the later ones like the creation of Bangladesh — ended in abject and irrevocable dictatorships, with some theocracies like Pakistan. Witness that no country on the Indian subcontinent is a democracy except India herself, in any legitimate sense of the word. So, on what historical or psychological basis can it possibly be said that Xi’s transition to power would lead to a personality-cult type of dictatorship? In an age where democracy is celebrated as mere dissent without any further positive movement to truly ground it, the more the competition and strife and demands — no matter what their nature or how degenerate they are — the better the prospects for democracy.

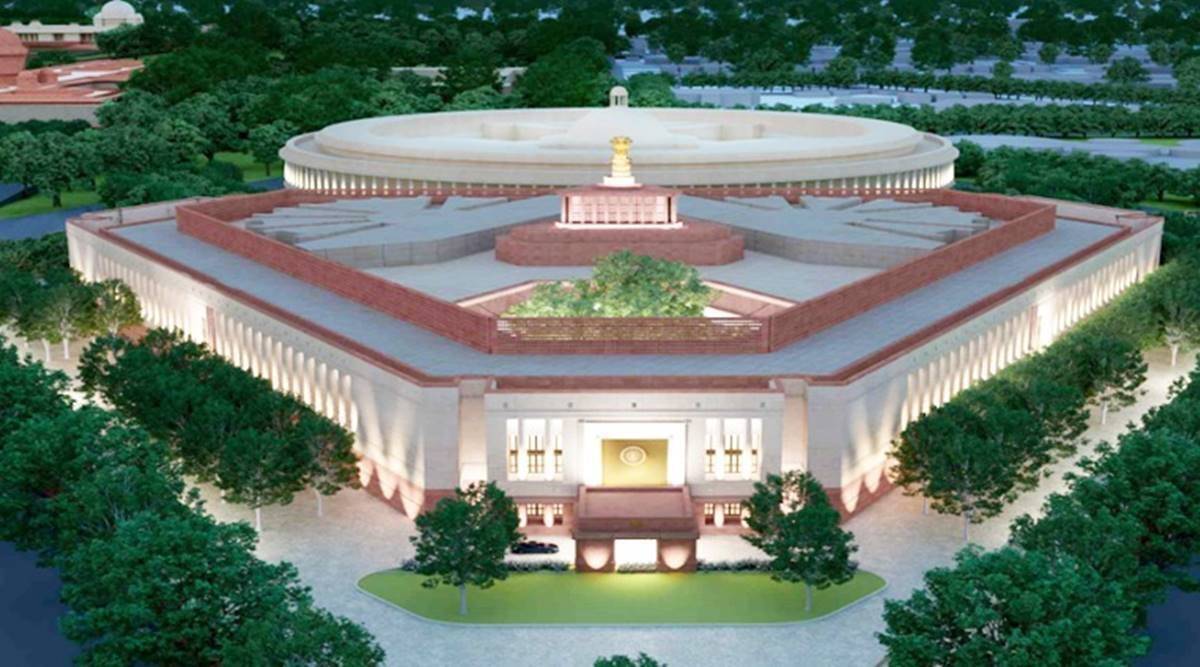

In contrast, Xi’s new transition to power is based on charting out a separate vision. The Modi Government, here, seems to be supporting the new development, with both India and China making favourable statements for each other and two key Union Ministers from India flying to China to discuss bilateral relations. But these overtures will be of little use unless India fully grasps the historicity and potential of India-China relationship.

(The writer is with the Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies and writes for The Resurgent India Trust)

Writer: Garima Maheshwari

Courtesy: The Pioneer

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)