In India, women’s struggle to gain working space continues. They form only 19.9 per cent of the total labour force, much below the halfway mark

Is gender stereotyping a thing of the past? No way! There are instances of sexism galore even in the “post-feministic” world. A widely circulated video on a popular social media platform showed how a “work from home” husband, hassled by his wife’s never-ending demands for participating in domestic chores, longs to get back to the office. The images, no doubt, reinforce the notion that domesticity is the women’s domain and the external world belongs to men.

In Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s recent Senate Judiciary confirmation meetings, her large brood found frequent mention and her commitment to motherhood was part of the public narrative. However, in the case of former Justice Antonin Scalia, his fatherhood and large family never found any mention.

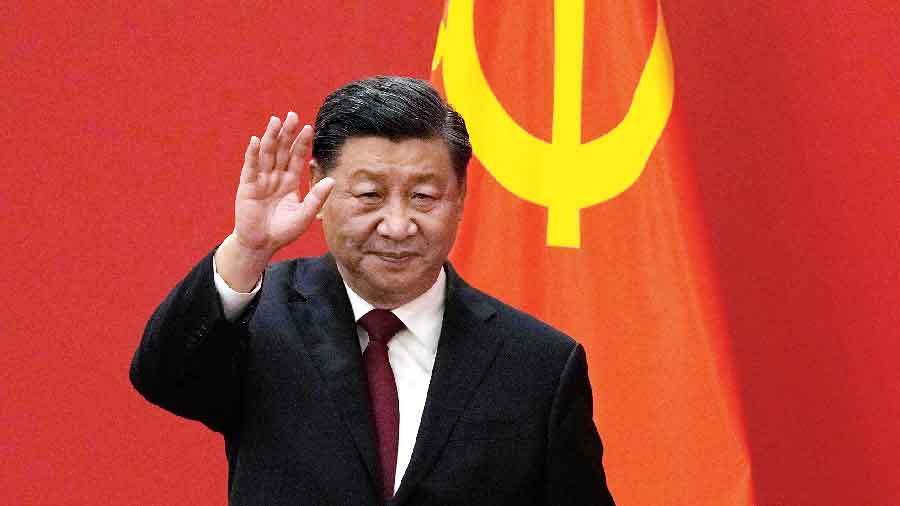

During the present pandemic, a handful of women political leaders earned applause for their effective containment strategies. In a crisis, their humility, inclusiveness, decisiveness and empathy touched the right chord with their beleaguered compatriots. It certainly unsettled the existing presumptions about leadership, which is often associated with “macho” qualities.

Roshee Lamichhane, Professor, Kathmandu University School of Management, rues that “gender stereotyping is deeply ingrained in the very process of child rearing, which, often metamorphoses a girl into a submissive creature, and endows a boy with overbearing character traits.” Saira Shah Halim, a social activist, author and film-maker, says that “the school curriculum and textbooks further sustain the rigid construction of gendered roles and condition the young minds with many cliches. For instance, D stands for a doctor, depicting a man, N for a nurse, with the image of a woman and that father goes to office and mother cooks at home and such gender expectations act as a deterrent in nurturing aspirations, choices or freedoms for many girls.” She further says that “even emotional responses are gender-specific, such as aggression, anger and violence are signs of manly behaviour, and consequently, women bear the burnt, despite a host of protective laws, as malefactors often find social support.”

The role of socio-religious forces cannot be undermined in fostering an inequitable power play in gender relations. The sacred Hindu literature, Manu Smriti, whose tenets still hold sway, spoke of imposing “tight control over women’s autonomy” and ordained women to be under the protective care of male guardians like a father, husband and son in different phases of their lives. Festivals like Karva Chauth, Raksha Bandhan, Shiv Ratri, et al are perhaps the outcome of such diktats. Some States in India are now mulling a law against inter-faith marriages or the so-called “love jihad”, possibly another attempt to impose a patriarchal writ on sisters and daughters in the name of saving family honour.

The popular entertainment industry is no less responsible in keeping alive gendered myths through its scripts, casting and dialogues. In 2014, a UN-sponsored study in the 10 most-profitable global film industries, including India, found that films often prop up beliefs that masculine traits and behaviour are more valued than feminine ones. In Hindi movies, women were only in 11.9 per cent of the films as central characters (2015-2017), which was only about seven per cent in the 70s, according to a study by the IBM and two Delhi-based institutions.

Katherine Coffman, a Harvard Business School Professor, asserts that “gender stereotypes determine people’s beliefs about themselves and others. If I take a woman who has the exact same ability in two different categories — verbal and math — just the fact that there’s an average male advantage in math shapes her belief that her own ability in math is lower.”

Researchers from Illinois, New York and Princeton Universities also found that girls as young as six years old tend to believe that brilliance is reserved for men, while a University of Warwick study says that “girls feel the need to play down their intelligence to not intimidate boys, pretending to be less intelligent than they actually are, not speaking out against harassment, and withdrawing from hobbies, sports and activities that might seem unfeminine.” Undoubtedly, trying to live up to such unreal ideas of masculinity and femininity leads to a tragic loss of potential in young people, especially in women.

In the US, women comprise half of the labour force, but only 26 per cent of them are employed in computer and math jobs, and occupy fewer seats in the C-suite than men, particularly in male-dominated professions like finance and technology. They earn almost 60 per cent of advanced degrees, but bring home less pay, due to “occupational sorting”, as men go for higher-paying jobs than women. While gender gap in pay is a universal reality, the recent case of the Princeton university paying lesser to its women professors proves that even renowned institutions are not immune to gender prejudices.

In India, women’s struggle to gain working space continues, being only 19.9 per cent of the total labour force, much below the halfway mark says the World Bank. Women remain poorly represented in core sectors of the economy like oil and gas (seven per cent), automotive (10 per cent), pharmaceutical and healthcare (11 per cent) and information technology (28 per cent). They earn, on average, 65.5 per cent less than their male colleagues for the same work, says a India Skills Report 2020.

In the STEM disciplines, women constitute nearly 43 per cent of the total enrolments but only three per cent enrol in PhD in science and six per cent in engineering and technology. A meagre 14 per cent of them work as scientists, engineers, technologists in research development institutions.

A 2018 IMF study indicated that women are prone to being displaced by technology as they perform more routine tasks, and about 11 per cent of them are likely to suffer from job losses for want of the required STEM skills by 2030. Kelly’s Workforce insights reveals that about 81 per cent women in the STEM sector confronted a subtle gender bias in performance evaluations. A large proportion of them felt that they wouldn’t be offered top positions and faced exclusion because of the presence of fewer women peers and leaders.

While commenting on prevalence of sexism in academia, Lamichhane says that issues like women’s looks and their linkage with career prospects remain contested, but, such a purported perception, often makes an impact on employees’ quest to look attractive. This proclivity has gravely impacted the sanctity of meritocracy and commodified the looks of women, while it is not a debatable issue at all for male employees.

Nevertheless, a recent lab research finding on the pre-historic skeletal remains excavated from the Andes Mountains has upset the applecart for gender stereotyping, which confirmed that women in large numbers used to be the big game hunters, and not gatherers alone, demolishing the millennia-old belief. Hasn’t this put into question the origin of gender binaries?

Sadly, the WHO and John Hopkins University’s joint study affirms the existence of all-pervasive “gender stereotypes around the world regardless of their country’s level of development.” Yet, many women, known and unknown, dared to defy the status quo and carved a new path for themselves. The milestone for bridging the gender gap may be a century away, a long journey, but not unachievable.

(The writer is a retired Indian Information Service Officer, and a media educator)

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)