An anti-intellectual attitude is often part and parcel of a politically influential middle-class that has a strong dislike for what it sees as ‘political elite’

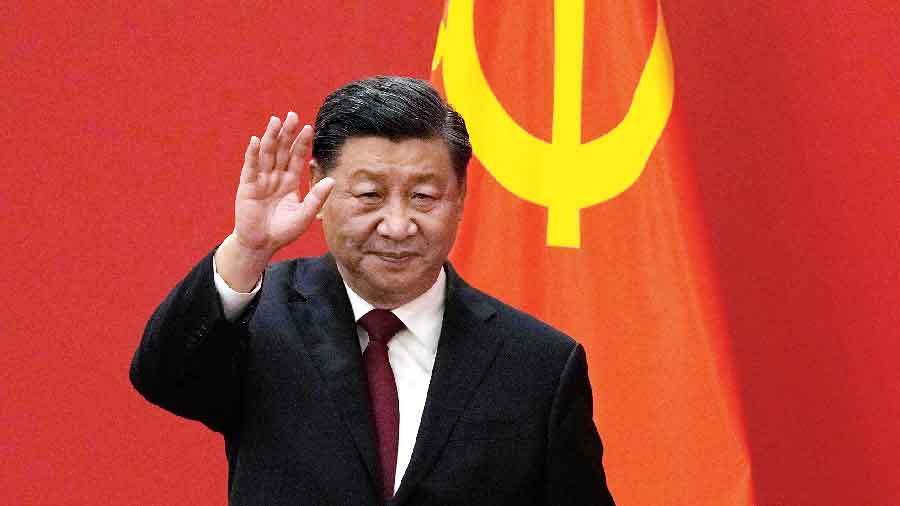

One point that supporters of Prime Minister Imran Khan really like to assert is that, “he is a self-made man.” They insist that the country should be led by people like him and not by those who were “born into wealth and power.” According to the American historian Richard Hofstadter, such views are largely aired by the middle-classes. To Hofstadter, this view also has an element of “anti-intellectualism.” He says that, as the middle-class manages to attain political influence, it develops a strong dislike for what it sees as “political elite.” But since this elite has more access to better avenues of education, the middle-class also develops an anti-intellectual attitude, insisting that, as a ruler, a self-made man is better than a better educated man. Khan’s core support comes from Pakistan’s middle-classes. And even though he graduated from the prestigious Oxford University, he is more articulate when speaking about cricket — a sport that turned him into a star — than about anything related to what he is supposed to be addressing as the country’s Prime Minister.

But many of his supporters do not have a problem with this, especially in contrast to his equally well-educated opponents, Bilawal Bhutto and Maryam Nawaz, who sound a lot more articulate in matters of politics. To Khan’s supporters, these two are “dynastic elite” who cannot relate to the sentiments of the common man. It’s another matter that Khan is not the kind of self-made man that his supporters would like people to believe. He came from a well-to-do family that had roots in the country’s military-bureaucracy establishment. He went to prestigious educational institutions and spent most of his youth as a socialite in London. Indeed, whereas the Bhutto and Sharif offsprings were born into power which is aiding their climb in politics, Khan’s political ambitions were carefully nurtured by the military establishment.

Nevertheless, perhaps conscious of the fact that his personality is not suited to support an intellectual bent, Khan has positioned himself as a self-made man who appeals to the ways of the common man. He doesn’t. For example, wearing the national dress and using common everyday Urdu does not cut it anymore. It did when ZA Bhutto did the same. But years after his demise in 1979, such populist antics have become a cliche. The difference between the two is that Bhutto was a bonafide intellectual. Even his idea to present himself as a “people’s man” was born from a rigorous intellectual scheme. However, Khan does appeal to that particular middle-class disposition that Hofstadter was writing about. When he attempts to sound profound, his views usually appear to be a mishmash of theories of certain Islamic and so-called “post-Colonial” scholars. The result is rhetoric that actually ends up smacking of anti-intellectualism.

So what is anti-intellectualism? It is understood to be a view that is hostile to intellectuals. According to Walter Houghton, the term’s first known usage dates back to 1881 in England, when science and ideas such as the “separation of religion and the State”, and the “supremacy of reason” had gained momentum. This triggered resentment in certain sections of British society who began to suspect that intellectuals were formulating these ideas to undermine the importance of theology and long-held traditions. According to the American historian Robert Cross, as populism started to become a major theme in American politics in the early 20th Century, some mainstream politicians politicised anti-intellectualism as a way to portray themselves as men of the people. For example, US Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodward Wilson insisted that “character was more important than intellect.”

Across the 20th Century, the politicised strand of anti-intellectualism was active in various regions. Communist regimes in China, the Soviet Union and Cambodia systematically eliminated intellectuals after describing them as remnants of overthrown bourgeoisie cultures. In Germany, the far-Right intelligentsia differentiated between “passive intellectuals” and “active intellectuals.” Apparently, passive intellectuals were abstract and thus useless whereas the active ones were “men of action.” Hundreds of passive intellectuals were harassed or killed in Nazi Germany.

According to the US historian of science Michael Shermer, a more curious idea of anti-intellectualism began to develop within Western academia as “postmodernism” had begun to hijack various academic disciplines in the 1990s. Postmodernism emerged in the 20th Century as a critique of modernism and derided it as a destructive force that had used its ideas of secularism, democracy, economic progress, science and reason as tools of subjugation. “Post-colonialism” or the critique of the remnants of Western colonialism was very much a product of postmodernism as well.

Imran Khan is a classic example of how “postmodernism” and “post-colonialism” have become cynical anti-intellectual pursuits. Khan often reminds us that social and economic progress should not be undertaken to please the West because that smacks of a colonial mindset. So, as his regime presides over a nosediving economy and severe political polarisation, Khan was recently reported as discussing with his Ministers whether he should mandate the wearing of the dupatta (a stole) by all women TV anchors. Go figure.

The views expressed are personal.

Courtesy: Dawn

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)