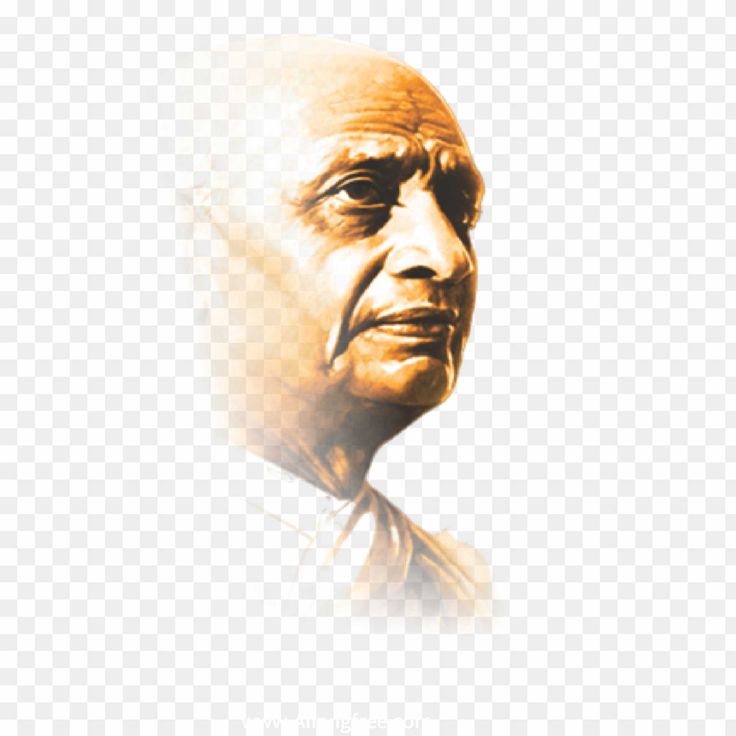

India’s Constitution bears the imprint of many hands, but few contributed as quietly and profoundly as Sir B. N. Rau — remembered today, 72 years on.

30 November marks the 72nd death anniversary of Sir Benegal Narsing Rau (1887–1953), the constitutional thinker whose scholarship shaped the foundations of India’s Republic. His contributions remain among the most significant yet least recognised in our constitutional history. Remembering him today restores a vital part of our national memory.

Born in Mangalore in 1887, Rau was the second son of Dr. R. R. Rau, a respected physician and educationist. His family produced several distinguished public servants, including a dean of Banaras Hindu University, an RBI Governor, and B. Shiva Rao, the parliamentarian-journalist who authored The Framing of India’s Constitution, the definitive chronicle of India’s founding. Rau’s own brilliance was evident early. Graduating from Presidency College, Madras with a rare triple first class, he proceeded to Trinity College, Cambridge, where even a young Jawaharlal Nehru described him in a letter home as “frightfully clever.”

Rau entered the Indian Civil Service in 1910 and developed a deep understanding of legislation and governance. Between 1935 and 1937, he undertook one of the largest legal reform exercises in modern Indian history: revising the entire statutory code after the Government of India Act, 1935. This enormous task — completed in less than two years — earned him a knighthood in 1938.

From 1939 to 1944, Rau served as a judge of the Bengal High Court at Calcutta. His ruling in GP Stewart v. B. K. Roy Chaudhury (1939) became a foundational precedent on legislative repugnancy, later affirmed by the Supreme Court in Tika Ramji (1956). He then briefly served as Prime Minister of Jammu & Kashmir (1944–45), gaining frontline experience in federal complexities.

His defining contribution began in 1947. On 29 August, the Constituent Assembly appointed Rau as its Constitutional Adviser. In just eight weeks, he produced the first complete Draft Constitution, a 240-article, 13-schedule document that offered India not merely a structure but a coherent constitutional philosophy. This draft became the base text that the Drafting Committee later refined.

The strength of Rau’s draft lay in his method. He did not imitate foreign models; he studied them with rigour. Travelling to the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Canada, he met judges, scholars and policymakers. He discussed judicial review with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, examined Irish parliamentary democracy, studied Canadian federalism, and absorbed lessons from European constitutional traditions. His aim was always adaptation, not imitation — to harmonise global constitutional wisdom with India’s unique social and political realities.

Among Rau’s most enduring contributions was the architecture of fundamental rights. He insisted that rights must be enforceable. Accordingly, he proposed a two-tier design: any law inconsistent with fundamental rights would be void, and the right to move the Supreme Court for enforcement would itself be a fundamental right. This concept later crystallised into Article 32 — the guarantee that constitutional promises would be matched by constitutional remedies.

Equally significant was Rau’s insistence on precision. Having examined the consequences of vague guarantees in other jurisdictions — particularly the American due process doctrine — he warned against broad language that could enable judicial overreach or legislative evasion. His Notes on Fundamental Rights reveal a careful balance between liberty and constitutional discipline, an equilibrium that continues to influence Indian constitutional interpretation.

After the Constitution’s adoption in 1949, Rau became India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations. His diplomatic clarity earned him wide respect. In 1952, he was elected a judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice at The Hague. Before his election, he was even regarded as a potential candidate for Secretary-General of the United Nations — an extraordinary recognition of his stature in international law.

Yet Rau remains little known outside specialist circles. Partly this is due to his temperament: he disliked public attention, preferred scholarship to rhetoric, and believed constitutional work should speak for itself. History often remembers those who occupy the podium, not those who labour quietly behind the scenes. But overlooking Rau diminishes our understanding of how the Constitution came to embody clarity, balance and intellectual depth.

On this 72nd anniversary of his passing, it is fitting to honour the scholar who helped give the Republic its constitutional soul. Sir Benegal Narsing Rau reminds us that democracies are built not only by leaders and legislators but by those who think deeply, draft meticulously and serve quietly. He remains one of modern India’s most remarkable, if least celebrated, architects — and remembering him today is an act of both justice and gratitude.

Dr. Charu Mathur, Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court of India. Views expressed are personal.

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)