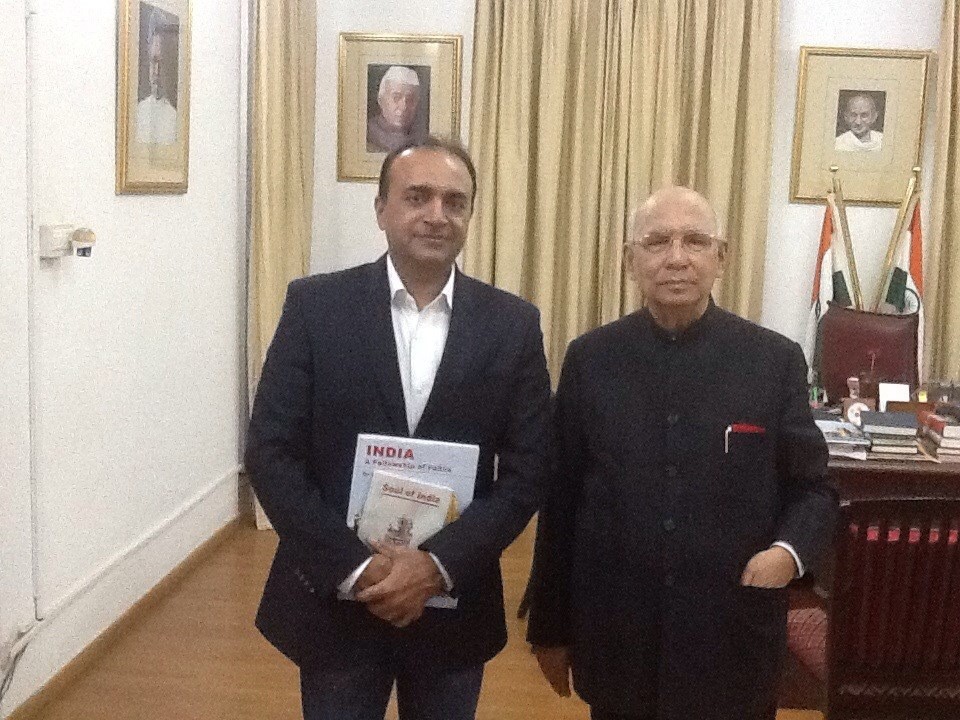

In picture: Prashant Tewari Editor-in-Chief of Opinion Express with then former Law Minister of India DR Hansraj Bharadwaj

HR Bhardwaj's tenure as the Law Minister holds a significant place in the annals of India's legal and political history while serving as the Law Minister from the early 1990s to 2009, Bhardwaj's vision and determination to reform and update the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) were noteworthy. However, his pursuit of these reforms was hampered by the lack of political support within the Congress party during that period.

The Indian Penal Code, enacted in 1860 during the British colonial era, and the Code of Criminal Procedure, formulated in 1973, are two of the cornerstones of India's criminal justice system. Over time, societal dynamics, technological advancements, and legal philosophy had undergone substantial changes. Bhardwaj recognized the imperative need to modernize these codes to reflect the contemporary challenges and values of Indian society.

Bhardwaj's commitment to reform stemmed from his understanding that the IPC and CrPC needed to evolve to address the complexities of modern crime, societal norms, and the principles of justice. His vision was to ensure that these laws remained relevant, effective, and equitable for all citizens. He aimed to strike a balance between protecting individual rights and ensuring the swift and efficient dispensation of justice.

During his tenure, Bhardwaj initiated a series of discussions, consultations, and debates to bring together legal experts, scholars, practitioners, and stakeholders to identify areas of reform within the IPC and CrPC. His approach was inclusive, seeking input from diverse perspectives to ensure that any amendments would withstand legal scrutiny and public expectations.

His visionary efforts to set up the timelines for the courts to decide on cases, and women-centric laws, promote Mediation and Arbitration to reduce burden on the active courts, limit the scope of appeals in the constitutional courts, set up mechanisms to evaluate judge's performance, declaration of assets by the judges mandatory to bring transparency in the courts, enhancement of salary and wages to the judges, selection of judges in the high and supreme courts through a consultation process between state government, state high court, supreme court collegium and finally the law ministry at GOI consent to be forwarded to President of India had established the best process to segregate judiciary from the government influence for maintaining the independence of the institution. Bhardwaj faced challenges within his own party, the Indian National Congress. The lack of political support can be attributed to various factors, including the non-majority government, the complex nature of legal reforms, differing ideological priorities within the party, and the broader political landscape of the time.

In the early 2000s, the Congress party was navigating a delicate balance between various factions and interest groups. The focus on economic reforms, social welfare policies, and other pressing matters often overshadowed the urgency of legal reforms. The party's leadership might have perceived IPC and CrPC reforms as less politically rewarding compared to other issues on their agenda.

Moreover, the Indian legal system is deeply entrenched in tradition, and any attempt to overhaul or amend such foundational laws can be met with resistance, skepticism, and concerns about unintended consequences. Bhardwaj's proposals for IPC and CrPC reforms might have faced opposition from those who were comfortable with the existing legal framework, fearing disruptions or dilution of their perceived rights and privileges.

Furthermore, Bhardwaj's tenure coincided with a period of coalition politics in India. The UPA government, led by the Congress party, relied on the support of various regional and ideological allies to maintain its majority in the Parliament. This intricate political web might have made it challenging to build consensus on comprehensive legal reforms, especially given coalition partners' varying viewpoints and priorities.

Despite these challenges, Bhardwaj remained steadfast in his pursuit of reform. He continued to advocate for the modernization of the IPC and CrPC through various forums, speeches, and engagements with legal experts. His passion for reform was evident, and he was often praised for his dedication to the cause of justice. He formulated several expert committees and the recommendations of the experts have been archived in the Law & Justice system wherein the recently proposed amendments by the Modi government have taken references from the past recommendations of HR Bharajwaj’s era. Everything in the new proposal remains the same as recommended in the past except the chapter and sections numbering have been changed.

In hindsight, the lack of support for IPC and CrPC reforms during Bhardwaj's tenure raises important questions about the dynamics of legal and political change in India. It underscores the complexities of aligning political priorities with the broader needs of the justice system and society at large. The episode also sheds light on the delicate balance that policymakers must strike between tradition and progress, between political exigencies and long-term vision.

While HR Bhardwaj's efforts to reform the IPC and CrPC may not have borne fruit during his tenure, his legacy as a visionary advocate for justice and legal modernization endures. Subsequent administrations and legal experts have continued to grapple with the need for comprehensive legal reforms, recognizing the evolving nature of Indian society and the imperatives of an equitable and efficient justice system. He famously quoted – “Give me a majority government, I will turn around the legal system of India” but unfortunately, he never had the occasion to be a law minister in a full majority Congress party government.

In conclusion, HR Bhardwaj's tenure as India's Law Minister stands as a testament to the challenges of enacting legal reforms within a complex political landscape. His vision to update and modernize the Indian Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure was laudable, but the lack of political support within the Congress party during his time hindered the realization of these reforms. Bhardwaj's legacy serves as a reminder of the intricate interplay between legal, political, and societal forces in shaping the course of justice in India.

Of course, Narendra Modi running the two majority governments having strong willpower to change the old bulky criminal justice system must be given the credit to initiate much-needed legal reforms to serve the 1.4 billion people, it is a welcome change but it needs fast adoption by the legal justice system that is operative at the ground. Similarly, the inclusion of technology and AI in the delivery of the justice system is a desperate requirement to tackle the loads that our courts have to carry while dispensing justice.

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (2)

Tremendous respect and admiration for Dr Hansraj Bharadwaj as India continues blossoming more beautifully stronger in many new ways in this world.

HRB was a legend.