Understand the burning issue

by Spoorthy Raman / 15 November 2019With a robust combination of the right policies, economic incentives and awareness campaigns, the problem of managing crop residue in an environment-friendly manner can be addressed

Delhi, one of the world’s most polluted cities, is in the news again for its worsening air quality as the Government has been forced to close schools and declare a health emergency. The much-loved winter months in other parts of the country are a nightmare for the residents of Delhi-NCR as the area gets enveloped in a blanket of toxic haze.

With the Air Quality Index (AQI) reaching new levels each year and going as high as 1,200+ (classified ‘Hazardous’) this month, the city is suffocating, literally. Apart from coal and construction dust, vehicular emissions and smoke from Diwali firecrackers, stubble burning by farmers in the States of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh (UP) are cited as the primary reason for this crisis.

While the Delhi Government has been trying to bring down pollution levels through its vehicle rationing odd-even scheme and by closing polluting factories and coal-based power plants among other things, biomass burning is something it has failed to stop. For this, it needs the cooperation of its neighbouring States and has no control over the farmers there.

Crop residue burning is a practice where farmers set their entire fields on fire after harvesting the rice crop, to make way for the next i.e. wheat. The sowing of rice is timed such that its intense water needs are met by the monsoon rains in the Indo-Gangetic plains and the crop is harvested just before winter starts. However, the result is a whopping 23 million tonnes of paddy residue in the fields that need to be cleared in a short span of 10 to 20 days, before the farms are readied for sowing wheat. If the farmers had more time between crops, they could have just left this biomass lie in the fields and let it turn to mulch, which is an excellent fertiliser. However, with such a short gap between the two crops, setting fields afire seems to be the easiest way to get rid of the stubble. This however severely degrades the ambient air quality of Delhi-NCR.

Taking cognisance of the consequences of stubble burning, the Government banned it in June, imposing fines on those who defied the diktat and recently the Supreme Court (SC) even pulled up the chief secretaries of the three neighbouring States and ordered them to ensure that farmers don’t burn crop residue anymore.

Nevertheless, the practice seems to have continued as growers contend that feasible, affordable and scalable alternatives are lacking. In an effort to encourage farmers to find alternatives to burning the residue, the SC had also directed the three States to pay Rs 100 per quintal of paddy straw to growers, but it doesn’t seem to have worked.

The atmospheric factors at play: People often wonder how a practice followed a few 100 km from Delhi-NCR has big implications. Here is the science behind this phenomenon. During winter, the region sees low wind speeds and temperature inversion — an atmospheric phenomenon where the temperature of the air near the surface is lower than that of the air higher in the atmosphere. Hence, when the pollutants from vehicular emissions and crop burning are released into the air, they are not dispersed but trapped in the lower layers of the atmosphere. As a result, the air quality takes a deep dive.

“Air pollution in cities like Delhi may be attributed to the growth of the metro and the pollutants from sources far away that get carried to the national Capital by the moving air or environmental conditions, which are unfavourable for the dispersion of pollutants,” said Prof Vinoj V from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bhubaneswar, talking about his study published in 2018. The study, among other things, had found that crop burning has been increasing at an alarming rate of 25 per cent since 2000.

It isn’t Delhi alone that takes the hit; other tier-2 cities in the region also seem to be affected by biomass burning for similar reasons. A 2019 research, which investigated the source of pollutants in 20 Indian cities other than Delhi, found that in places like Amritsar, Chandigarh and Ludhiana, crop residue burning, along with emissions from power plants and seasonal dust storms contributed to about 50-52 per cent of particulate matter.

In essence, the timing of winter-related atmospheric phenomena, coupled with the surge in emissions when the fields are set on fire, is a perfect pollution cocktail.

The health and economic costs of stubble burning: It is well-known that inhaling polluted air can lead to severe health conditions like lung cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, bronchitis and dementia. Not just this, air pollution also adversely affects crop yields in India. But, what really is the economic cost of stubble burning in these maladies?

A study, published by researchers at USA’s International Food Policy Research Institute and Oklahoma State University, pegs that number at $30 billion, including the economic loss and associated health costs. It found that about 14 per cent of acute respiratory infections, recorded in Haryana, Punjab and Delhi in 2013, could be attributed to stubble burning. Researchers estimate that living in areas where there is intensive crop burning increases the chance of acute respiratory infections three-fold, with children under the age of five being the most affected.

Crippled policies adding to woes: As most studies have pointed out, a robust combination of the right policies, economic incentives and awareness campaigns are the need of the hour to curb the “burning” problem of air pollution. Badly-designed policies could have unintended effects on air quality, as shown by a research from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in India and Mexico and the Cornell University, USA. It showed that groundwater conservation policies, introduced in 2009 in Punjab and Haryana, could have contributed to the rise in stubble burning.

Although rice is a lucrative crop for farmers, it is water-intensive. Hence, the ‘Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Water Act’ and the ‘Haryana Preservation of Subsoil Water Act’ banned the transplantation of rice before monsoon to conserve groundwater. As the monsoon arrives in these States in July, the crop is harvested in early November, forcing farmers to clear their fields as soon as possible for wheat sowing. Using satellite data, the study found that prior to 2009, about 40 per cent of rice was harvested by late October and this number declined to 14 per cent after the law was enforced. The number of fires went up from 490 per day during late October prior to 2009, to 681 per day, peaking around early November. The average daily PM2.5 concentrations in November were also found to be 29 per cent higher after the groundwater Acts were passed.

With the clamour for alternatives to stubble burning increasingly being heard, science may have solutions, as shown by a 2019 study. It analysed 10 alternatives to stubble burning and found that contrary to what farmers believed, these methods were not only environment-friendly, but also profitable. Among them is using Happy Seeder, a machine that can sow wheat despite the presence of rice straw in the fields. This yielded nearly 10-20 per cent increase in profits or about Rs 11,498 per hectare on an average. The profits come from lower land preparation cost and the reuse of the crop residue, which increases soil moisture and benefits the long-term health of the soil.

However, these benefits come at a cost of Rs 2.4 billion — necessary to produce about 16,000 Happy Seeders to cater to 50 per cent of the rice — wheat cultivation areas. With a meagre subsidy of Rs 2,000 provided by the Government for purchasing machines to manage crop residue, machines like Happy Seeders are unaffordable to many farmers, leaving them with no options but to set fields on fire.

As most of these studies have pointed out, with a robust combination of the right policies, economic incentives and awareness campaigns, the pressing problem of managing crop residue can be addressed. It is about time that policymakers took note of such insights and acted to provide us all with clean air to breathe — a basic necessity of life.

Writer: Spoorthy Raman

Courtesy: The Pioneer

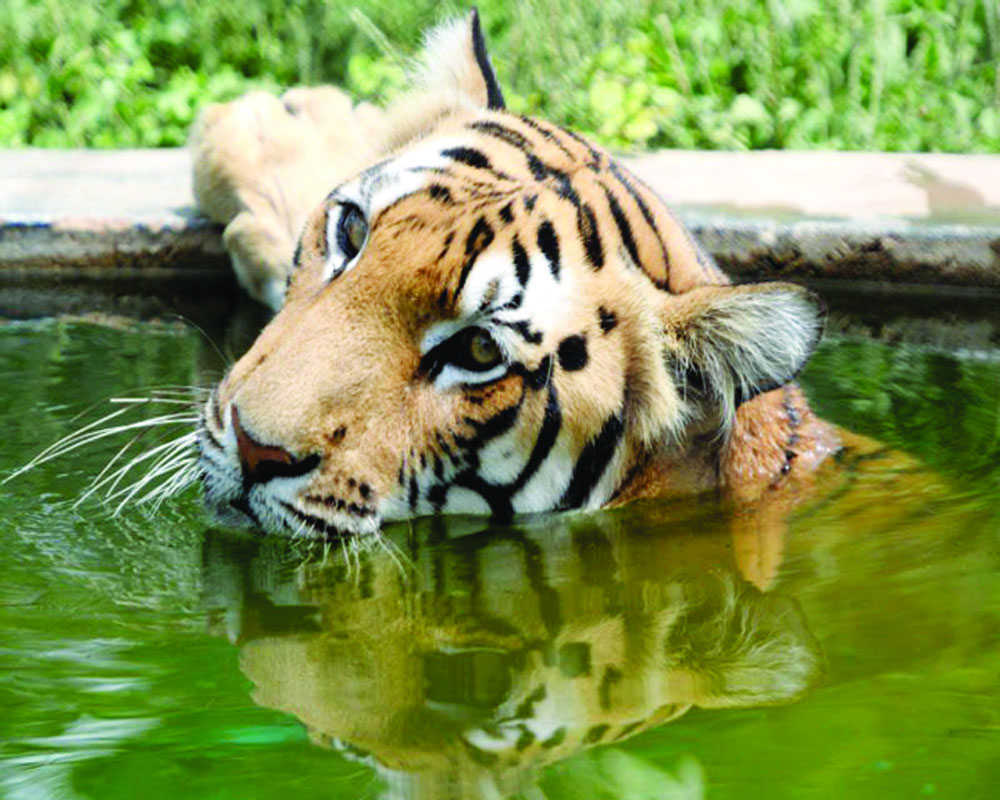

Challenges Against Increasing Tiger Population

by VK Bahuguna / 10 September 2019Issues like conditions of forests, prey base, livelihood of fringe forest dwellers, tribals and so on need to be taken up on a priority basis so that the big cats don’t come in conflict with people

On the occasion of the International Tiger Day, Prime Minister Narendra Modi released the 2018 Tiger Estimation report with great fanfare and broke the news of a significant increase in the tiger population of India. He termed the success of tiger conservation efforts in India as “baaghon mein bahar hai,” a take on the popular Hindi film song from yesteryears. According to the estimation report, the tiger population has increased from 1,400 in 2014 to 2,967 in 2019, a solid growth of 34 per cent. It is a remarkable achievement for the country that in spite of several hiccups in conservation, it has three-fourth of the world’s tiger population and has emerged as the safest habitat for the big cat. Highlighting India’s conservation efforts, Modi said that the target to double the tiger population by 2022, which was set in 2010 in St Petersburg by the international community, was achieved by India four years in advance.

The tiger census, one of the world’s largest, was carried out over an area of 3,91,400 sq km in 3,17,958 sample habitat plots. As many as 26,838 camera traps located at 141 sites covered over 1,21,337 sq km of forests and snapped more than 76,000 pictures of the big cats.

This estimation seems quite reliable given the meticulous planning, use of cutting-edge technology and analytical tools. This time human errors were minimised and figures were based on recording of actual field data digitally through the mobile phone application M-STrIPES (Monitoring System for Tiger-Intensive Protection and Ecological Status). The sighting of tigers and other animals was recorded and geo-tagged. One of the keys to success was the adoption of a landscape approach across five tiger habitats, i.e. the Shivaliks and Indo-Gangetic Plains, Central India and Eastern Ghats, Western Ghats, the North-East and the Sunderbans. National Geographic prepared a documentary on this census, highlighting the hard work done by the field staff and other officers.

The increase in tiger numbers in the country has basically been due to the hard work put in by the foresters and positive attitude of villagers apart from policy thrust and priority attached to conservation by the Centre and State Governments.

The impact of improvement in overall forest management and technological back-up was also felt. However, we must also remember that the tiger is a prolific breeder and once its numbers started growing, a good prey base and habitat ensured that the population would register good growth. But the nation must give equal credit to villagers situated near tiger habitats as without their cooperation, protecting the feline species would have been a pipe dream, as is the case in many other countries. However, the increased tiger population has brought with it more responsibility and challenges for forest departments as tigers can only prosper in healthy environs that would support their prey base.

Incidentally, the highest number of tigers, 526, was located in Madhya Pradesh (MP), followed by 524 in Karnataka and 442 in Uttarakhand.

Sadly, Chhattisgarh witnessed a big decline from 46 tigers in 2014 to 19 in 2019 and is a cause for concern. Similarly the results in Bihar, Goa, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Mizoram and Arunanchal Pradesh are not very encouraging and the situation may become critical in other areas also. Shockingly, no tigers were reported in Buxa, Palamu and Dampa tiger reserves.

However, a word of caution for MP, Uttarakhand and Karnataka which have shown a boost in big cat numbers. They must control the increasing man-animal conflicts as a larger tiger population means increasing competition for food, water and space. Issues like conditions of forests, prey base, livelihood of fringe forest dwellers, tribals and so on, need to be taken up on a priority basis so that the big cats don’t come in conflict with people. Further, water sources will have to be improved on a war footing to combat climatic vagaries.

The Ministry of Environment’s Compensatory Afforestation Planning and Management Authority (CAMPA) recently released Rs 47,000 crore to States. Even if the annual interest earned on this amount is used in a well-planned manner, it can solve the monetary and resource crunch faced by the forest department.

There is also dire need to synchronise the working of forests, rural, tribal affairs and Jal Shakti Ministries. The time is ripe to make some innovative and forward-looking changes in the governance of these subjects.

(The writer is a retired civil servant)

Writer: VK Bahuguna

Courtesy: The Pioneer

On The Verge of Losing Fauna

by Kota Sriraj / 16 August 2019The effects of habitat destruction, overexploitation of natural resources and degree of climate change is continually threatening the survival of wildlife species. To protect and reverse this effect, the government needs to take quick action.

By any standard, forests around the world are the last barriers between mankind and the ill-effects of climate change. How the human race has so far managed to stay outside the grasp of worsening environmental conditions is a miracle and can be attributed to the neutralising capabilities of the forests and their inherent wildlife.

But the health of our forests largely depends on the health and the number of wildlife species they host. It is also a fact that this insurance cover against the vagaries of environment is now depleting at a rapid rate. There has been a 53 per cent decline in the number of forest wildlife populations since 1970, according to the first-ever global assessment of forest biodiversity by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Wildlife is an essential component of natural and healthy forests. They play a major role in forest regeneration and carbon storage by engaging in pollination and seed dispersal. Thus, the loss of fauna can have severe implications for forests’ health, the climate and humans, who depend on forests for their livelihoods, said the WWF report titled, Below the Canopy. Until now, forest biodiversity had never been assessed but forest area was often used as a proxy indicator.

The new findings were based on the Forest Specialist Index, developed following the Living Planet Index methodology — an index that tracks wildlife that lives only in forests. In total, data was available for 268 species and 455 populations of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. Of the 455 monitored populations of forest specialists, more than half declined at an annual rate of 1.7 per cent, on average between 1970 and 2014.

While the decline was consistent in these years among mammals, reptiles and amphibians (particularly from the tropical forests), it was less among birds (especially from temperate forests), said the report.

Further, the report found that just the changes in tree cover — deforestation or reforestation — were not responsible for the decline in wildlife populations. Other major threats were habitat loss, forest exploitation and climate change. In fact, the loss of habitat due to logging, agricultural expansion, mining, hunting, conflicts and spread of diseases accounted for almost 60 per cent of threats.

Nearly 20 per cent of the threats were due to overexploitation. Of the 112 forest-dwelling primate populations, 40 were threatened by overexploitation (hunting), the report showed. Climate change, on the other hand, threatened to 43 per cent of amphibian populations, 37 per cent of reptile populations, 21 per cent of bird populations but only 3 per cent of mammal populations. More than 60 per cent of threatened forest specialist populations faced more than one threat, the report noted.

Not only are forests a treasure trove of life on earth, they are also our greatest natural ally in the fight against climate breakdown. Protecting wildlife and reversing the decline of nature require urgent global action. The need is to preserve harmonious land use in our region, including forest management and protect the most valuable surviving ecosystems. Given these circumstances, there is an urgent need for global leaders to kick start an action plan immediately to protect and restore nature and keep our forests standing. Only a quarter of the land on earth is now free of the impacts of human activities.

In a bid to conserve nature, world leaders have agreed to launch a ‘New Deal’ for Nature and People in 2020 in China. The new set of commitments will likely draw together a global biodiversity framework with reinvigorated action under the Paris Agreement and the United Nations-mandated Sustainable Development Goals.

The state of affairs of our forests is not at its best phase. Nations across the world are aware about the growing problem of disappearing forests and wildlife, which is becoming extinct. India, too, is no stranger to this situation but unlike the global forum, our country is yet to take concrete steps that can ensure that our forest remain replete with ample flora and fauna. The annual forest reports and allied data show that since independence, India has lost quite a lot of forest cover, mainly due to man-made reasons than climate change. The usurping of forest land by land mafia is emerging as the biggest reason. This situation is made worse due to poaching activities, which put an end to wildlife.

How can the Government or the judiciary stem the loss of green cover in India and prevent wildlife from poaching remains to be seen. The Government must ensure that Indian forests are treated with priority and protect the wildlife within. Unless immediate measures are taken, the loss for our country would be permanent and the green barrier that stands between us and impacts of climate change would be gone forever.

(The writer is an environmental journalist)

Writer: Kota Sriraj

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Big cat’s leap of faith

by Hiranmay Karlekar / 03 August 2019An increase in its population is gratifying but the tiger still faces problems, including the frequent man-animal conflicts. A national-level strategy is needed to manage this interface

Jim Corbett wrote in the Man-Eaters of Kumaon, the “tiger is a large-hearted gentleman with boundless courage and that when he is exterminated —as exterminated he will be unless public opinion rallies to his support — India will be the poorer, having lost the finest of her fauna.” Had the legendary hunter-turned conservationist and writer been alive, he would have noted with relief the contents of the latest estimation report on the number of tigers, titled the Status of Tigers, Co-Predators, Prey and their Habitat, 2018, released by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on July 29, annually observed as Global Tiger Day. The report puts the number at 2,967, which marks an increase of 33 per cent over the figure of 2.226 in the estimated tiger count in 2014 and a phenomenal 210 per cent over the 2006 figure of 1,411.

The increase is gratifying because it comes as a part of a continuing upward trend since 2006. Besides it represents one of the few instances in which the Union or a State Government’s efforts have succeeded. It all started in 1970 when the Union Government banned the hunting of tigers throughout the country. Two other important developments followed in 1972. The country’s first tiger census put the number of the striped lords of the jungles at 1,827. More important, Parliament passed the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, for protecting animals, birds, reptiles and plants. It prohibited the capturing, killing, poisoning or trapping of wild animals, the injuring, destroying and removing any part of a wild animal’s body, also forbade disturbing or damaging of the eggs of wild birds and reptiles. It further prohibited the picking, uprooting, destruction, acquisition and collection of specified plants and trade in these. The Act also provided for the creation of sanctuaries and national parks where wildlife would be safe and for restriction of entry into these. More, it provided punishment for each category of crime.

The Act was an important step as the Wild Birds and Animals Protection Act of 1912 (eight of 12) and the various State laws prevailing until then offered little protection. It was, however, aimed at wildlife in general and not specifically tigers. For the latter, Project Tiger was launched on April 1, 1973, with two objectives — identification of the causes of shrinking tiger habitats, adoption of remedial measures and repair, to the extent possible, of the damage already done; and, second, the maintenance of a viable tiger population.

The project’s distinguishing feature has been the creation of sanctuaries, called Tiger Reserves, to protect tigers from poaching and other threats. Against nine spread over 9,115 square kilometres at the beginning, there are now 50 of these encompassing an area of 74,749 square kilometres. No human activity is allowed in their core areas, while limited access is granted to the buffer zones around these. Strong action is being taken against poaching with rangers and forest guards being provided wireless communication systems, improved weaponry and facilities for rapid movement.

Funded by the Union Government, administered by the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MOEFCC), and functioning under the direct supervision of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), set up under the provisions of the Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2006, Project Tiger has made the most important contribution to increasing the number of tigers. One, however, has also to take into account the efforts made to protect wildlife from crimes against it, which has helped significantly, particularly since poaching to meet the demand abroad for tiger body parts for their allegedly medical and aphrodisiacal value, has been a contributory factor in the decline in numbers. In this context, one needs to recognise the critical role played by the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) set up in 2006 under the same amendment act that established the NTCA.

A statutory multi-disciplinary body under the MOEFC, to combat organised wildlife crime in the country, it collects and collates intelligence pertaining to organised wildlife crime and disseminates the same among State and other enforcement agencies for immediate action. Its functions also include the establishment of a centralised wildlife crime data bank, co-ordination of actions by various agencies in enforcing the Act’s provisions and assistance to foreign authorities and international organisations to facilitate global action against wildlife crime. Among other things, it also helps to improve the capacity of agencies combating wildlife crime to conduct scientific and professional investigations and assists State Governments to successfully conduct prosecution for the same.

A proud feather in its cap has been the United Nation Environment Progamme’s conferring on it in November last year of an Asia Environment Enforcement Award in the Innovation category for successfully innovating enforcement techniques that have dramatically improved action against trans-boundary environmental crimes in India. Earlier, in 2010, it had received the prestigious Clark R Bavin Wildlife Law Enforcement Award for outstanding work on wildlife law enforcement. Not surprisingly, its actions, along with those of other enforcement agencies, have resulted in the arrest of 350 wildlife criminals and huge seizures of tiger/leopard skins, rhino horns, elephant ivory, turtles/tortoises, raw mongoose hair, mongoose hair brushes, protected birds, marine products, live pangolins, deer antlers and so on across the States.

There is, however, hardly any scope for complacence. Human-tiger conflicts are becoming more frequent as the increase in the number of tigers continues along with growing human encroachments into their habitats in the form of new settlements, more extensive farming, infrastructure, and environmentally-disastrous industrial projects benefitting blue-eyed entrepreneurs. In this context, there is an urgent need to implement the NTCA’s suggestion for developing a national level strategy for management of human-tiger interface and dispersing tigers in compliance to its standard operating procedure, ensuring active collaboration between district administrations, police and forest department personnel, and, when required, for mob management to ensure safe capture or movement of animals.

All this, however, will not help if State Governments clear projects threatening the tiger’s survival. Two examples come immediately to the mind. Maharashtra sanctioned last year the diversion of 467.5 hectares of forest land in Yavatmal district for a cement plant. Also, its recommendation has led to the clearance, in principle, of 87.98 hectares of land in Kondhali and Kalmeshwar ranges — barely 160 km from Yavatmal — to an explosives company in Chakdoh for manufacturing defence products.

Unfortunately, tigers do not vote. Nor do they contribute to the funds of political parties.

(The writer is Consultant Editor, The Pioneer, and an author)

Writer: Hiranmay Karlekar

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Tiger tales on International Tiger Day

by Opinion Express / 30 July 2019Yes, the numbers of the big cat have doubled but so has the intensity of man-animal conflict. Let’s address that too

In 2008, alarm bells had rung when the tiger census in the country threw up a dismally low number of 1411, despite years of initiatives under Project Tiger. Home to 70 per cent of the world’s wild tiger population, India had no option but to turn the needle through aggressive pursuit of various conservation efforts. So it is indeed heartening that in little over a decade, we now have almost doubled that number, clocking 2,967 tigers and registering an increase of almost 33 per cent in the fourth cycle of the latest census. Little wonder then that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who released the new figures, seized another moment of national pride that India has achieved by claiming that the target of doubling the tiger population has been met four years before the deadline. What makes the numbers remarkably reassuring is that they have come at a time when biodiversity is severely challenged. Yet the government and the community have persistently been in sync with their conservation efforts. Also the four-year counting exercise, the world’s largest wildlife survey effort in terms of coverage and intensity, is a celebration of technology. Over 15,000 camera traps were installed for capturing tiger images and recording their unique stripe pattern with the help of a dedicated software, there were satellite mapping and GIS-based apps for in-depth tracking of the big cats and the data collection process. Madhya Pradesh saw the highest number of tigers at 526, followed by Karnataka at 524 and Uttarakhand with 442 tigers. So it is the healthy patches which have pushed up the total numbers rather than the dotty ones.

This brings us to the most important aspect of tiger management in their habitats than just recording figures. While tiger numbers have increased, tiger habitats have been dwindling due to human encroachments, infrastructure projects and truncated wildlife transit corridors. The man-animal conflict has never been worse, therefore. Be it the killing of Avni or villagers beating up straying tigers, or the confused tiger hitting back with a counter-charge, the headlines point to a dangerous trend of overpopulation not being commensurate with increase in prey base-rich forest zones. The Wildlife Trust of India’s conflict database for Uttar Pradesh records 63 cases of attacks on humans by tigers from 2014 to February 2019, an average of 10.8 cases per year. This marks a dramatic increase from an average of 5.6 attacks on humans per year between 2000 and 2013. The tiger will stray into human settlements when its food chain is frayed and villagers cannot be expected to prioritise conservation when the lives of their own and the livestock are at stake. It is now imperative to understand what’s causing the conflict on the ground on a case by case basis and address it immediately before avenging kills start showing up in the numbers. Awareness of tigers should now also include equal awareness about its ecology and behaviour and the need to provide alternative ranges. Recent examples have shown how some railway underpasses to facilitate wildlife transit are working as animals, like the elephant and tiger, are adapting to changed migration routes. There are still viable tracts of pristine forests that can be turned into reserves by relocating animals from overpopulated stretches. But forests are a state subject and an inter-state agreement on shared corridors needs to be ironed out and coordinated if translocation is to succeed. Meanwhile relocation needs are mounting. The entire process cannot be fast-tracked but needs to be graded and spaced out to ensure tigers’ acceptance of a new territory as their own household. Apart from peripheral villagers, a new tiger also has to deal with resident cats or in the total absence of its kind, reconcile to being a lone ranger and sync up with other relocated companions. And if forest dwellers have co-habited with tigers before, there is no reason why we cannot make them stakeholders in conservation efforts, keeping them invested as park patrollers and monitors, generating a subsidiary tiger economy that ensures them revenue, incentivising forest produce and enhancing the tiger gene pool that can promote “sighting tourism.” Till this is done, our pride will continue to be their enemy. The tiger sits on top of the food chain in the forest and by saving it and giving it a home, we are protecting all sub-species and curating a biosphere that even includes grasslands and rivers.

Writer & Courtesy: The Pioneer

Not so Impactful Tiger Protection Act

by Opinion Express / 18 June 2019The odd killing of elephants by tigers at Corbett is not just aberrant behaviour, it is about survival

Tigers tend to get maligned every time they display aberrant behaviour and become the subject of alarmist headlines that make them a feared monstrosity rather than the endangered species that they could become. Yet the fact of the matter is we need to study the conditions and reasons for their uncharacteristic behaviour and mutations and factor them in future wildlife conservation policies. The latest Government study, done with the Corbett National Park authorities, which has found that park tigers have killed and eaten elephants, at first sounds incredible and unbelievable. Considering the different physical dimensions of both creatures and the fact that elephants move in herds, a tiger’s kill potential indeed seems microscopic. But it is not impossible, considering the tiger is remarkably agile, adaptive, has penetrative canines and claws and is extremely intelligent, isolating stray members of any pack animal before the hunt. Elephant calves can become its prime target, even borne out by the study which says that carcasses of the young were the maximum among the 60 percent deaths because of tiger attacks. Besides, the big cat attacks the trunk, the major food conduit of the elephant which usually dies on its own subsequently, unable to eat and nourish itself back to health. Also, as the Sundarbans tiger has shown, the big cat can alter hunting behaviour according to its location. For example, African leopards have taken down the largest antelopes as elands, greater kudus and wildebeests, though they are more than five times heavier than their own size. Lions, too, there have taken down elephant calves. Which is why the study is worrying wildlife experts as tigers usually don’t eat elephants and this could be the beginning of a new intra-wild species conflict.

Not that the alerts haven’t been there. Instances of tigers charging at elephants have been fairly videographed in Corbett. We also seem to have not learnt our lessons despite isolated cases settling down into a patterned behaviour. In 2017, six elephants died in Kerala’s Wayanad wildlife sanctuary in tiger attacks, triggered as they were by bitter turf wars over scarce water in a drought year. Tigers are already bearing the brunt of over-population, reduced roaming territories and prey base, broken habitats and migration corridors as well as human encroachment. All this is challenging their primal instincts and forcing them into evolving survival tactics given the context they find themselves in. So cattle-lifting and man-eating are not just about an old territorial tiger anymore but regulars who are getting accustomed to easy prey options. Even Corbett in-charge Sanjiv Chaturvedi admitted that tigers “need comparatively less amount of efforts and energy in killing an elephant as against that needed in hunt of sambhar and cheetal. It is large quantum of food for them too.” He said the national park has a unique ecosystem with more elephants than tigers, 1,100 against 225, unlike other national parks like Ranthambore, Kanha and Bandhavgarh. Does this mean that Corbett tigers are working out their own kill choices depending on easy availability of a stray calf or a sick pachyderm? That they are feeding on elephants, which were killed in herd infighting, also proves that they are changing the rules of hunt and game. Does it mean they are prioritising easy availability as evidenced in tiger attacks on elephants in Kaziranga too? If this is an emergent crisis, then we need to develop strategies to save both species. Buried in the report is also the fact that most tiger deaths are because of infighting over mating and territorial rights. Has the tiger then been literally pushed into a corner?

Writer & Courtesy: The Pioneer

Need to Save the Big Cats of India

by HS singh / 11 June 2019Besides Project Tiger, our achievements were also possible because wildlife conservation is deep rooted in the Indian culture and tradition

India, a mega-biodiversity country with diverse climate and natural habitats in the world, is the last hope for the survival of several mega-mammals, including big cats on planet Earth. Of the seven big cats — lion, tiger, jaguar, puma (mountain lion), common leopard, snow leopard and cheetah (hunting leopard), five were found in India. But one of them — hunting leopard — exterminated from the Indian sub-continent in the early 1950s. Clouded leopard, a cat occurring in the north-east of India, is also considered a big cat by some naturalists but it falls slightly short of the minimum size of the big cat as its average weight is just below 20 kg.

India’s wildlife richness is incomparable in the world. It were the invaders, who brought a culture of reckless hunting, impacting the abundance of mega-mammals. According to official records, over 80,000 tigers, more than 150,000 leopards and 200,000 wolves were slaughtered between 1875 and 1925. About 300 lions were hunted around Delhi during 1957-58 a few years after independence. All four big cats have disappeared from their previous habitats in Asia or are surviving in restricted habitats in small numbers. But their story in India is different. Their survival depends on their conservation here in India where they still have viable populations despite high human population.

The Asiatic lion, which had extensive distribution in West Asia to India, has a restricted population in the Gir forests in Gujarat. They disappeared from the northern and western parts of the country. At present, over two-thirds of the global population of the tiger is found in 17 States in India. The number of other sub-species of the tiger in other countries in Asia is very small and none of them has over 500 individuals. Similarly, out of about 20,000 Asiatic leopards in about two and half dozen countries in Asia at present, 15,000- 16,000 individual leopards are estimated in India alone. Status of snow leopard is not known but there is no sign of any significant decline of its number in high altitudes of the Himalayas.

Occasionally, scientists and conservationists played the numbergame by providing population figures which suited to their academic greatness. Some of the figures quoted by naturalists and referred in the scientific documents and papers are far from the truth. Hence, the history of these big cats needs to be renewed. For example, the Nawab of Junagadh and some naturalists quoted about dozen remnant numbers of the Asiatic lion in the beginning of the 20th century. It has also been quoted in all scientific literature. If Asiatic lion’s number was one dozen in the first or second decade of the 20th century, then how could it reach to 287 individuals in the first Asiatic lion census in 1936? Annual hunting records also denied the low figure. In fact, logically, the Asiatic lion population never dropped below 50 during its entire history. Scientists and naturalists presented distorted and wrong history of this species. The present number of over 600 lions, perhaps over 700 as locals believe, is a healthy population spreading in four districts, although the threat from epidemic disease is high due to increased predation on domestic livestock, dogs and domestic animal carcasses. Loss of habitats outside the Protected Areas is also a matter of concern. The lion conservation landscape in Junagadh, Amreli, Gir-Somanath and Bhavnagar support about 1,300 big cats (over 600 lions and over 650 leopards). The numbers suggest human-wildlife conflict is a matter of concern.

Future of the tiger also lies in India. Although its habitat and distribution shrunk in the country, it is still found in about 90,000 sq km area in 17 States. In the past, some naturalists quoted a figure of 40,000 individual tigers in India at the beginning of the 20th century. This figure, too, has no scientific basis. After the declaration of Project Tiger, the population of this big cat was estimated over 1,800 individuals, which increased consistently and doubled in three decades. A reverse trend started due to massive poaching, after the success of its conservation. The camera image trap method for tiger counting in 2006 quoted a population of 1,411 individual tigers in India. Naturalists played the numbergame again. They publicised a decline by half. There was over-reporting of the number of tigers by some States using the pugmark method of counting, but the decline was not as drastic as highlighted by non-field conservationists.

Undoubtedly, the disappearance of tiger from four reserves, including Panna and Sariska, was a conservation blunder. The hullaballoo that followed resulted in the birth of National Tiger Conservation Authority. In 2006, tigers were never counted in Jharkhand, Sundarbans and North-East of India, Naxalite affected areas and also other forests area where few nomadic tigers occurred. Also, only sub-adult and adult-tigers were counted and cubs below one and half years, which constitute about 30 to 35 per cent of the population, were not accounted.

The numbers were again wrongly put. If all these are accounted logically, tiger population, including cubs, was not below 2,000 individuals in 2006. In 2014, the number of sub-adult and adult tiger was about 2,230 individuals, which was about 65 per cent of the global tiger population. With cubs, the number was perhaps about 2,800-2,900 individuals. Initial survey in 2018 revealed that the number has gone up due to strict protection measures India’s tiger habitats can support about 3,000 individuals of sub-adult and adult tigers. With growing human and industrial pressure in the previous habitats and around the tiger reserves, protection of dispersing tiger is difficult.

Leopard, a versatile cat, has very high adaptive capacity. Its population was never estimated accurately due to the concealing behaviour of the smart cat. The surveys of this cat in different States reveal that about 15 per cent to 20 per cent leopards are found outside the national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and forests. The tea gardens, sugarcane fields, ravines and agricultural fields have become habitats for the leopards. Expanding irrigation network turned beneficial to this cat. In 1964, EP Gee, a known wildlifer, quoted a figure of 6,000 to 7,000 leopards in India. He also mentioned that the number was 10 times in the beginning of the 20th century. This figure is quoted in all scientific documents. However, even with advanced technology, wildlife managers failed to estimate its accurate population. So, how could a naturalist guess a population of 6,000-7,000 leopards in 1960s? Recently, a conservation organisation in collaboration with Karnataka Forest Department projected an unbelievable population of 2,500 leopards in Karnataka. As per the recent reports, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka each has an estimated leopard population of over 2,000 individuals. Gujarat and Chhattisgarh each has over 1,000 leopards. Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal and Odisha have over 500 or nearly 1,000 leopards. Leopard occurs in 29 States and one Union Territory and its present population is estimated about 15,000-16,000 in the country. Although leopard presence is in over two and half dozen countries in Asia, none has above 1,000 of the species. Only Iran has nearly 1,000. It is, thus, a matter of great pride that about three-fourth of the total Asiatic leopard survives in India.

Conservation achievements of these big cats were possible because wildlife conservation is deep rooted in the Indian culture and tradition. Indian mythology, ancient art, literature, folk lore, religion, rock edicts and scriptures, all provide ample proof that wildlife enjoyed a privileged position in India’s ancient past. Kautilya’s Arthashastra, a book written in the third century BCE, reveals the attention focussed on wildlife in the Mauryan period: Certain forests were declared protected and called Abhayaranya like the present day ‘sanctuary’. Heavy penalties, including capital punishment, were prescribed for offenders who entrapped or killed elephants, deer, bison, birds, or fish, among other animals. Lord Mahavir Jain, Gautam Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi always advocated Ahimsa towards living creatures.

The ashrams of rishis, which were sites of learning in the forests, were frequently visited by the animals. The Vedas, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the Upanishads, the Puranas, the Arthashastra and the Panchtantra are among the many texts of ancient India that deal with the influence of forests and wildlife on human society. Ashoka, the most powerful monarchs, who put lions at the top of rock pillar, was a staunch wildlife conservationist.

Another key factor for survival of carnivores in India is never considered in analysis. About 524 million livestock in India provide major food to carnivores such as big cats, canines, hyena, small carnivores and raptors. Nearly half of the food for lions comes from hunting of domestic animals or their carcasses. Leopard is largely dependent on dogs, sheep, goats, poultry, other domestic animals and their carcasses. The tigers also extract substantial food from livestock abundantly available around the Tiger Reserves.

(The writer is Member, National Board for Wildlife)

Writer: HS singh

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Wildlife in Danger

by Hari Shanker Singh / 09 January 2019If you thought that rabies concerned only dogs, then one must look back to the records at the King Edward Memorial Pasteur Institute and Medical Research Institute, Shillong. It had published a scientific article in 1950 recording two instances of a positive microscopic finding in the brain — evidence of rabies — of the Bengal tiger in Assam, the first in 1943 and the second in 1950. In the first case, the tiger severely mauled 18 people in just over 24 hours before it was killed but made no attempt to eat any of the victims. In the second case, the tiger terrorised the inhabitants of five or six villages and attacked 14 people, at least five heads of cattle and a dog, of whom one person and the dog were killed on the spot and two others died in hospital the following day. Subsequently, the animal was killed.

The rabies virus was found in both cases. And though these two cases were examined following complaints of unseemly behaviour, several others were ignored. A few cases of leopards dying ostensibly due to rabies were also reported in south India during the British period. The rabies-inflicted stray dogs, living on the boundaries of Kruger National Park in South Africa and other reserves, are threats to predators such as lions, leopards, hyena and wild dogs. Perhaps deaths of predators by rabies do not get the exposure they deserve. The veterinary advisor for the Siberian Tiger recommended the vaccination protocol for use in all wild tigers to save them from viral disease.

Four years ago, a similar behaviour was observed in two lions — first was a male lion in Girnar on May 31, 2011, and the second was a young lioness in the Khamba range of the Gir forest on December 15, 2015. In both cases, the frenzied felines chased people and attacked a few of them, including the forest staff. The injured people were vaccinated and saved but both lions died within a few days. Symptoms like biting of tyres and frequent roaring in the daytime indicated the presence of rabies but cases were never examined to know the truth. The extent of damage by the fatal Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) attack, ostensibly a mutation or aggravation caused by the rabies virus, was taken seriously only when 23 lions died in September 2018 in the Gir forests.

In the past, deaths of the lion by virus attacks were detected but ignored because the number was not high. Unlike the lion, tigers or leopards do not live in groups. Thus, death of one or two of them at a site by the fatal disease was ignored. It was recorded as a natural disease but facts prove otherwise. Almost every other day, news reports cite the recovery of dead leopards, tigers, lions and several other carnivores from their habitats but the cases have never been examined by virologists to confirm the cause of deaths.

In a study, four concomitant incidents of rabies related deaths were recorded in Gujarat during 2012-2014. Brain samples were collected from two buffaloes, nilgai and mongoose and rabies virus was found in all of them. Further, the genetic relationship of these isolated specimens was determined and the rabies virus transmission among the wild and domestic mammals was established. In Deva village in Allahabad district, two cows and a young buffalo cub were bitten by a rabies-infected dog. All died within two weeks. Finally, the dog was killed and the carcass was disposed off in a remote area of the village. What had happened to carnivores such as jackals and foxes, which consumed the carcass, is not known but the villagers confirmed that the carnivores had not been spotted. Why is it that the jackals are fast disappearing from the villages? Why are the hyenas becoming rare in the countryside? Why is it that the population of the wild dog (dhole) declined drastically in its habitats such as the Satpura Tiger Reserve and then recovered in a few years and again declined drastically? Is it due to the spread of rabies or any other virus? Has rabies’ presence in the domestic dog caused the loss of wildlife in an unbelievable scale? Perhaps yes. Casualties of the major wild carnivores in India due to transmission of rabies, CDV, FIV or other viruses are high but it is impossible to provide facts about the scale of the crisis. After the lion deaths due to a CDV attack in the Gir forests, investigations indicated that like the African lions, the CDV and other viruses are present in some wild lions in the Gir forest. All of these become fatal when other diseases such as Babesia protozoa are transmitted from an unhealthy prey.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported that rabies is a vaccine-preventable viral disease which occurs in more than 150 countries. Dogs are the source of a vast majority of human rabies deaths, contributing up to 99 per cent of all rabies transmissions to humans. Human deaths due to rabies are known and have been well-documented but it is also primarily a disease of terrestrial mammals, including dogs, wolves, foxes, jackals, big cats (lions, leopards and tigers), mongooses, badgers, bats and monkeys. Rabies is endemic to India and accounts for 36 per cent of the world’s human deaths due to this disease. The true burden of rabies in our country is not fully known; although as per a WHO report, it causes 18,000-20,000 deaths every year. Nobody knows how many wild carnivores die due to this disease. India had over 19.1 million domestic dogs in 2007 and a majority of them belonged to the category of feral or stray dogs. A substantial number of this forms the prey base for carnivores, especially for leopards, tigers, lions, hyenas, wolves and jackals.

In India, dogs play an important role in rabies transmission to wildlife. However, little is known about the role of wild animals in rabies transmission. As per a study in the US, the rabies disease unexpectedly re-emerged in wildlife. Rabies is a viral zoonosis associated with many species of carnivores, including cats, jackal, hyena and bats, which are the primary hosts of the Rabies virus. Although sporadic cases of rabies in wildlife have been documented across the African continent, convincing evidence for the circulation of rabies in populations of wild carnivores has been found only in south Africa, where wild canids, such as jackals and bat-eared foxes, are assumed to be primary hosts of the virus. Although wolves, wild dogs, jackals and foxes are susceptible and readily succumb to the disease, they can disseminate the disease in other wildlife.

The carnivores — lion, tiger, leopard, hyena, wolf, and jackal — are susceptible to diseases as they largely prey upon domestic animals, including dogs and pigs which are a carrier of pathogens. Domestic livestock, including dogs, constitute major food for these wild animals. Cases of tiger and leopard deaths are reported from time-to-time, but the institute engaged in the field of wildlife research does not give priority to such an important problem. In the absence of adequate studies, it is difficult to assess deaths of wild carnivores due to rabies but it seems a major hurdle, although not accepted till date of wildlife conservation in India.

To eliminate rabies in wildlife, ‘progressive control pathways’ and procedures for international certification of rabies-free status should be established. To achieve this, wildlife managers should know the extent of the problem. The sample of every dead animal should be examined scientifically in institutes that deal with wildlife or virology. Institutes, too, need to focus on the scale of natural deaths rather than just concern themselves with environment impact assessment (EIA). It has taken us long to maintain a healthy population of the big cat. Let us not lose them to another threat.

(The writer is Member, National Board for Wild life)

Writer: Hari Shanker Singh

Source: The Pioneer

The Animal Kingdom

by Opinion Express / 07 January 2019A feel-good image of a lioness nursing and feeding a two-month-old leopard cub, who got separated from its mother, along with her two new-borns in Gir made for a touching act of compassion, showcasing the maternal and protective instincts of the animal world and restoring our faith in the laws of the natural world to take care of itself.

The lioness has been protecting the cub for six days now, feeding it with milk and taking care of it as that of her own cubs who are three-month-olds. While friendly interactions between species are relatively common, the uniqueness of this alliance lies in the fact that the adoption happened between two felines who are believed to be enemies. Lions and

leopards are not exactly friends and stay away from each other. In fact, the pride of the lion, as it is known, lies in it being a predator — killing any animal, including the leopards — to eliminate any future competition for food or to ensure that their own progeny survives to adulthood. Social as they are by nature, the pride of their grouping, that can range from a collation of two or more than 20 male or female related species, lies in protecting their territory and offspring. Their relationship is such that they can recognise any of their kind by sight or roar. So resilient they are that they can distinguish their cubs from others, which once in the king’s sight, is most likely to be killed. Females, on the other hand, remain close to each other to do the most gruelling task: To give birth and nurse their cubs communally. It is this psychology primed in their minds, to take care of baby cats, that helped the baby leopard find a shelter among the lioness’ own cubs. Physically, the cubs can hardly be distinguished. The lioness has also been taking care to ensure that the big alpha males do not prey on the cub as is their given behaviour. Though cats are not offensive when their prey base is not an issue, constricted and broken forest corridors and human depredations have resulted in changes in their behaviour. Which is why the lioness’ act stands out in a hostile wildlife climate.

A similar pairing was also witnessed in Tanzania two years back when a five-year-old lioness, who had lost her own cubs, was seen nursing a week-old leopard cub. Further, the King of the Jungle may not be the only ones to form odd alliances. Similar has been the story between a dog nursing a squirrel and that of a deformed dolphin being welcomed into the whale family. The lion-leopard story also offers lessons in humanity, especially in times when we are increasingly witnessing human-wildlife conflict that has resulted in the disappearance of these rare species. We, being humans, must also be empathetic towards protecting wild creatures. There can be no better a legacy as remarkable as that of inter-species coordination in protecting creation.

Writer: The Pioneer

Source: The Pioneer

High Time for Animal Accident Prevention

by Opinion Express / 21 December 2018The Gir lion is living on the edge with a widely fragmented habitat and human encroachment, the latest news of a pride of three being mowed down by a goods train in Gujarat’s Amroli district prompting a debate on whether infrastructural development factors in the welfare of the wild enough. The accident happened in the midnight hour with neither the train driver nor the lions, three in all, able to figure out how dangerously close they were to each other. Although investigations are on to determine if the goods train driver was complying with speed limits set for transiting wildlife corridors or if the forest trackers were doing their job of monitoring animal movement, fact is we need to strongly pursue an accident prevention scheme for wildlife along our rail tracks. The existing infrastructure has been in long use, and though it bifurcates forest corridors which animals use to disperse into new territories, any future accident prevention module has to work around this reality. Cases of elephants, tigers, leopards and other species being run over by trains are not new, our elephant deaths along tracks being the highest in the world. And we have been attempting to control them through several measures like the installation of warning signs for train drivers in sensitive stretches, night patrols along tracks and introducing staff to assist with elephant crossings since 2002.

This was also replicated in Assam in 2008 with some success. But with the railway networks spreading and high speed corridors soon to become a reality, a unified railway policy needs to be worked out on a predictive model. Even the West is besieged by similar issues of track accidents and has tried out or proposed several remedial measures. Some have mooted the idea of reflectors to warn incoming animals of a possible impact zone, others have talked about some fencing in stretches or erecting olfactory barriers that involves spraying a foam of predator scents, including that of man, on vegetation and structures nearer the track. Poland, in fact, introduced a “key stimuli proxy”, a device emitting acoustic signals of natural sounds which aggravate the fear factor in animals, deterring them from approaching the tracks or straying off their habitat. But the problem with artificial control is that animals, and particularly an intelligent one like the lion, can evolve and mutate once they sense a mechanised pattern. A far cheaper option then, as many wildlife experts have suggested, would be to build overpasses or underpasses where tracks cut through wildlife habitats, allowing the animals the right of way safely.

We have somewhat reconciled ourselves into believing that humans cannot have territorial curbs but animals must be squeezed in their shrinking ranges and be forced to adapt. This lopsided policy has resulted in Gir lions spilling out of their ranges and almost cohabiting with villagers, letting go of their feline aggression for a tamer behavioural adjustment. More lions will stray in the absence of a transit to an alternative home. With the latest incident, the number of lions, including cubs, having died in and around the Gir forest since September has reached 35. While some of them have died of natural causes, many others fell prey to Canine Distemper Virus (CDV), protozoa infections and territorial fights necessitating isolation. Our national pride is indeed struggling to roar.

Writer and Courtesy: The Pioneer

Wildlife Protection Needs to be Tied to Respect for Nature

by RK Pachauri / 13 November 2018Protection of wildlife can see real results only after we give respect to nature and acknowledge its values.

Gandhiji was always concerned about how we humans treated animals, because he felt that the life of an animal was no less valuable than that of a human being. He said this in so many words when he offered his view that, “To my mind, the life of a lamb is no less precious than that of a human being.” Against the reality of rapid depletion of wildlife across the world we are also reminded of Gandhiji’s witty response to a question on what he thought of wildlife: “Wildlife is decreasing in the jungles, but it is increasing in the towns.”

There are societies which are large consumers of meat, but quite paradoxically a few of them show interest in preserving wildlife. Factory farming, which characterises the global meat industry today, distances the consumer from the birth and life of the animal which is consumed. Sir Paul McCartney, a strict vegetarian himself, said, “If slaughterhouses had glass walls, everyone would be a vegetarian.” This paradox was in evidence in the mid-1970s when beef prices went up and some people in the US started consuming horse meat in certain locations. This led to widespread protests and expression of revulsion, with bumper stickers appearing in some places saying, “horses should be in the stable, not on the table”.

The motivation for protection of wildlife in such societies arises out of an appreciation of the cosmetic appeal of some endangered species like tiger, cheetah, polar bear and panda. Parents often say that they would not want their grandchildren to see these animals only in pictures; hence, any efforts at conservation of the species is driven by aesthetic appeal and the entertainment value of wildlife.

For much too long even in India killing a tiger or leopard was seen almost like the red badge of courage. How many portraits have we seen of visitors of importance from Britain being treated to a tiger shikar with the ultimate picture of the dead animal, and the ‘brave’ shooter standing with a gun in his hand and his foot on the head of the slain tiger?

Today, despite strong legislation and global agreements, the threat to wildlife, whose numbers have reached precarious levels, comes from poaching and the general encroachment of human activities on the habitat of species in the wild. In such a situation when a hungry carnivore cannot find adequate food, it ventures to seek easy game in human habitation. In so many cases the affected community attacks the predator to protect its livestock.

Today, the threat to animals and species in the wild has reached an unprecedented level. The World Wide Fund (WWF) has done remarkable work in assessing the frightening expansion of humanity’s footprint on the earth’s increasingly fragile ecosystems. ‘The Living Planet Report’ (LPR), a comprehensive and rigorous compilation of the state of the earth’s natural resources and ecosystems, is produced every two years, and the WWF has just brought out its 2018 edition, which provides chilling details of the damaging effects on the irreplaceable bounty of nature as a consequence of what we call economic development.

The LPR 2018 estimates and concludes that “on average, we’ve seen an astonishing 60 per cent decline in the size of populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians in just over 40 years”. What is particularly alarming is the trend that we are seeing in the direction of over-exploitation of species across the globe. The President and CEO of WWF Carter S Roberts states, “Natural systems essential to our survival — forests, oceans, and rivers —remain in decline. Wildlife around the world continue to dwindle. It reminds us that we need to change the course. It’s time to balance our consumption with the needs of nature, and to protect the only planet that is our home.”

The fundamental flaw in our pattern of growth and development lies in the fact that nature provides us with a wealth of ecosystem services, but the market values these as zero, and there is no system by which price of these services can be included in the costs of goods and services produced by the human society.

As a visionary economist said several decades ago: “Nature has no checkout counters.” Hence, we treat the global commons as a free good, leading to their precarious condition today. Yet, as the LPR 2018 estimates, on a global basis, nature provides services worth around $125 trillion a year, and more than that, nature ensures the supply of fresh air, clean water, food, energy, medicines, and much more, all of which we devalued heavily.

Overall, populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians have, on average, declined by 60 per cent between 1970 and 2014, the most recent year with available data. The Earth is estimated to have lost about half of its shallow water corals in the past 30 years; and a fifth of the Amazon has disappeared in just 50 years.

There is a very small window of opportunity for us to act and prevent irreversible disaster. In the case of climate change, we are the first generation to understand the science and risks of climate change but we may be the last generation to be able to solve the problem. Similarly, as the LPR 2018 states: “We are the first generation that has a clear picture of the value of nature and our impact on it. We may be the last that can take action to reverse this trend. From now until 2020 will be a decisive moment in history.”

The so-called “great acceleration” has brought the human society unprecedented benefits in the areas of overall rise in our health, wealth, food and security, but the benefits are very unequal across society. And these benefits have come at a huge cost in terms of the disappearance of the wealth of biodiversity and nature. And, yet as the LPR states, nature underpinned by biodiversity provides a wealth of services which are the building blocks of modern society. But biodiversity is being destroyed rapidly. Hence, the protection of wildlife may have a certain romanticism behind the meagre efforts that we see around us, but unless we develop a reverence and value for nature and biodiversity, these efforts would remain futile and ineffective.

Writer: RK Pachauri

Courtesy: The Pioneer

FREE Download

OPINION EXPRESS MAGAZINE

Offer of the Month