China against Hong Kong’s Pro-Democracy Movement

by Opinion Express / 06 August 2019China’s restrictive ways are only magnifying the pro-democracy movement and costing the economy

It seems discussions and contraventions around “special status” have even thrown civilian life completely out of gear in Hong Kong, as pro-democracy activists continue to make their point despite crackdowns and teargas fury. Things have come to such a pass that around 100 flights have been stopped in and out of the semi-autonomous southern Chinese city. Triggered by opposition to an extradition law to mainland China — that was subsequently put on hold — the stir has snowballed into a wider movement for democratic reforms and autonomy as mandated by its historical special status. And given the size of Hong Kong’s economy and global vibe, even China cannot overlook the opposition in its stressed times. A British colony for more than 150 years, China also leased the rest of Hong Kong to the British for 99 years. It became a busy trading port, and post-1950s became quite the economic powerhouse. Over time, it became an island of opportunity, attracting migrants and dissidents who fled persecution in the mainland. And though China ensured a return of Hong Kong to itself in 1997, it was under the conditional principle of “one country, two systems.” So, apart from foreign and defence affairs, Hong Kong is empowered to develop its own legal system, borders and rights, including the ones on free speech and peaceful protests. But with the heaving approach of Premier Xi Jinping’s “China first” mantra, there have been insidious ways of meddling in Hong Kong and muzzling pro-democracy legislators. Its Legislative Council has been defanged as most members aren’t chosen directly by Hong Kong voters and are pro-mainland.

These frictions have been building up over time and the extradition order was just the last straw on the camel’s back. The restlessness is now a galloping civil movement, spearheaded by the young, who want an identity and a life independent of the oppressive idea of being a “global Chinese.” China cannot steamroll this movement any longer and risk further negativity or renewed demand for full independence. And though it is wondering how far should it endure before kicking in with familiar ways, it knows that bottling gaps may lead to a bigger pipe bursts of anger. Besides, could it risk its business interests in the world’s most expensive piece of real estate and trading volumes? Technically, Hong Kong’s special status ends in 2047. But can China hold out with its belligerence till then without addressing political demands of its people to have a say about their lives?

Writer & Courtesy: The Pioneer

Pipe dreams

by Opinion Express / 03 August 2019The Hyperloop promises to revolutionise travel but questions remain about its economic viability

The world is littered with expensive transportation infrastructure projects that are barely used and even abandoned after a few years. There is the famous example of a brand new airport near Madrid, Spain, which was abandoned after a few months. In 2002, China inaugurated a magnetic levitation train between the Pudong airport and the outskirts of Shanghai, the harbinger of a massive network of space age connectivity. While that train remains the world’s fastest commercially operating train, with speeds touching 500 km per hour, it is nothing more than a tourist attraction today. The 30 km rack cost an eye-watering $1.2 billion in the early-2000s and it should serve as a cautionary tale for those who want to make India a hub for the new ‘Hyperloop’ technology. In essence, Hyperloop is ‘Maglev Plus.’ Magnetic levitation lifts a ‘shuttle’, which travels through an enclosed pipe. It operates ideally, in a vacuum, but realistically with very low air pressure, allowing the shuttles to move without any air resistance at up to 1,000 km per hour. Such a system would make immense sense then as a transportation system between urban agglomerations located close to each other. Such as Mumbai and Pune, and it is no surprise that those who back the technology feel that this will make for a great test track. Sure, reducing the three-four hour travel time by road between Maharashtra’s industrial hubs will be welcome but there are several caveats. First, there is little certainty on who will fund this extremely extravagant programme. While the Maharashtra government has given it ‘infrastructure’ status, the State government and the Centre are not investing any money. The estimated project’s price is a truly sky-rocketing $10 billion, and that is before the inevitable cost escalations, since the technology itself is currently in its testing phase.

Would the money be better spent on developing a regular high-speed train track between the two cities that tunnels through the Western Ghats instead? Or should money be poured into a unproven technology with immense potential but possibly still years, possibly decades away from commercial application? Will the Hyperloop in India end up like the Maglev track outside Shanghai, a tourist attraction that showcases the future that might have been? It is one thing to look at the future, but practicality should also come into consideration. Massive, futuristic infrastructure projects and technologies get politicians goggly-eyed but running headlong into something without thinking it through is plain silly. Has anyone asked the question on who will use the ‘Hyperloop’ between the two cities? If the project costs a bomb, then only the very rich or tourists can use it. After all, in Shanghai, locals prefer taking the regular, slow subway train instead of the Maglev. We do not have the luxury of building infrastructure to make a point, we have to build infrastructure to be used by a billion people.

Writer & Courtesy: The Pioneer

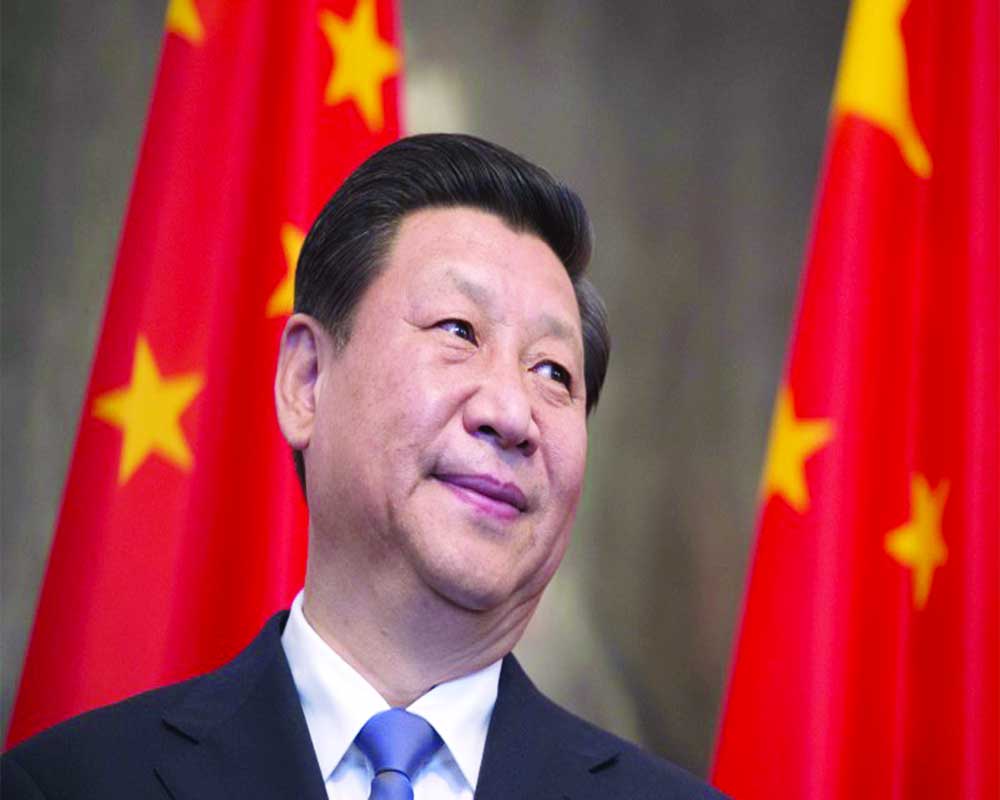

Xi Jinping’s visit

by Abhijit Bhattacharyya / 01 August 2019Ahead of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit, India will do well to complete its homework — from symbolism to business

On July 22, an amusing news item caught everybody’s attention. The visit by the Communist Party of China leader and state President, Xi Jinping, to India in October depended primarily on the runway length of the Indian airport. “A runway big enough for the aircraft carrying Chinese President Xi Jinping and his large high-powered delegation to land directly from Beijing is believed to be one of the key parameters when the Indian and Chinese sides jointly decide the venue for the second informal summit in India between President Xi and Prime Minister Narendra Modi,” said the report.

Several points, therefore, emerge on the runway alone. First, if it becomes one of the prime issues regarding the visit and venue of the Sino-Indian bilateral, then it’s up to the host nation, India, to take the call because once a sovereign nation hosts a top dignitary of another sovereign nation, it’s the duty and responsibility of the former to take care of and fulfil all parameters of safety, security, hospitality and protocol among other things. Second, if the guest raises the airport runway length of the host as an issue three months before the visit, then the bilateral looks more like a logistics-centric exercise than a serious diplomatic discussion. Third, does the unusual “runway length” shift the focus on to poor airport infrastructure in India’s backyard, which the Chinese guest would like to see as a business opportunity for “upgradations?” Fourth, is it a Chinese ploy to play with and point out the vulnerability and backwardness of the host? To show India in poor light in front of the world? Through wide media coverage?

If so, understandably the airport “runway” has its ancillaries, too, under the scanner. Leave road, hotel, transport, communication, media facility, security and hospitality aside. There is a need for ample room for VVIPs to move around and stroll in solitude. There are expectations of an informal, intimate and private set-up with spacious arena, beyond the gaze, or radar, of the “excessively inquisitive” media, being in tune with the philosophy and standard set long ago by disciples of the Marx-Lenin duo.

Coming back to the Indian airport and Chinese aircraft for the Sino-Indian bilateral, it may not be far-fetched to visualise Xi alighting from a four-engine US-made Boeing 747 as there is nothing else in the vicinity, notwithstanding the existence of the sole four-engine Airbus 380 of Europe.

Assuming again that Airbus 380 could be one of the options for the flight of the Chinese leader, as reportedly China Southern Airlines operates five such aircraft, in reality, it’s highly unlikely. Only four Indian airports of Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Hyderabad have the facility and capability to handle super-jumbo Airbus 380, the maximum take-off weight of which is between 510 and 575 tonnes.

Hence, it’s almost certain that only a fully-laden four-engine US Boeing 747 will be the preferred aircraft with a maximum take-off weight between 362.875 tonnes and 442.250 tonnes (depending on the model and date of manufacture). That takes us to the possible Indian venue of the meet, which has to be the same city for the foreign dignitary. Thus, whereas there exists more than 30 international airports in India’s map, handling aircraft of various size, shape and capacity for diverse destination, only the top 10 longest airport runways could be considered for visiting Chinese dignitary.

These 10 are New Delhi 4,430 metres (14,534¢); Hyderabad 4,260 metres (13,976¢); Bengaluru 4,120 metres (13,517¢); Chennai 3,662 metres (12,020¢) and 2,935 metres (9,629¢); Kolkata 3,627 metres (11,900¢) and 2,790 metres (9,150¢); Ahmedabad 3,599 metres (11,807¢); Mumbai 3,445 metres (11,302¢) and 2,990 metres (9,760¢); Kochi 3,400 metres (11,154¢); Amritsar 3,289 metres (10,790¢) and Thiruvananthapuram at 3,400 metres (11,154¢).

We can now say with a reasonable degree of confidence that the Boeing 747 of Xi will land at one of these 10 airports. Why? Because a fully-laden Boeing 747 (a VVIP like Xi arriving in India cannot come in an aircraft without full load owing to various obligatory safety, security parameter and protocol) takes anywhere between 7,000¢ and 8,000¢ length runway for landing and between 9,950¢ and 10,600¢ for take-off. That said, every flight also requires an additional 2,000¢ to 3,000¢ length for manoeuvring, in case of an aborted take off or emergency landing. And one simply cannot take any chance with high-profile visit of an important head of state.

So, once decided, one would like to ask: Which airport would be preferred for Xi’s October visit? Here, I dare suggest, if I was there, I would unhesitatingly suggest Kolkata as the venue for the Indian Prime Minister to welcome the Chinese President for an “informal bilateral visit.” Absurd? Impossible? Hallucination? No. Not at all. It’s real. Practical. Art of turning impossible into possible.

Too much political bickering between Delhi and Kolkata is reaching an unacceptably high decibel, thereby creating an irreparable rift between the Centre and the whole of the East and North-East. Perennial neglect and snubbing of the East and the North-East is creating a cleavage with potential long-term damage. Hence, hold the meeting in Kolkata to equalise its strategic value as a gateway to our Look east policy, China having already consolidated its economic hold on Southeast Asia. The distance between the Kolkata airport and Raj Bhavan can be covered through the aerial route. Dum Dum to Race Course, under Eastern Army Command, is six-eight minute flying time, and Race Course helipad to Raj Bhawan would be a maximum three-four minute drive for VVIP motorcade.

The river-front of Hooghly, from Eden Garden to Princep Ghat, could easily be spruced up again under the Eastern Army Command. Hotels of Taj Bengal and Oberoi Grand could be had for the entire entourage. Those coming by road from airport to hotels could easily cover the distance through fly-overs in 30 minutes, under controlled protocol of traffic guards.

Politically and diplomatically, it can very well be a win-win situation for all. Delhi could show political sagacity. Kolkata its traditional magnanimity. And the Chinese guest could have a reunion with those Chinese who made Bengal their home almost 100 years ago when China (especially Shanghai) was on fire, from May 4, 1919. There still are Chinese, who do Durga Puja in China Town and have even written slogans in Chinese language during the last parliamentary elections.

There, however, is one knotty issue: The date of the visit. If it’s Durga Puja/Nava Ratri, it has to be between October 2 and 8. The only thing which, perhaps, needs to be avoided is that it may not be between October 20 and 31. October 20 because India was attacked by China on that day in 1962. Hence, all 11 days from October 20 to 31, when India was being mauled by the PLA, may not give politically the right signals. October 1 will be the 70th birth anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. We all compliment China on its 70 years, but Beijing, too, needs to understand the sentiment of Indians for mutual reciprocity pertaining to goodwill and harmony. Hence, to my mind, a visit between October 6 (Ashtami) and October 8 (Dussehra) could be ideal. Both diplomatically as well as internally. It reminds me of the book by General William Slim, Defeat into Victory.

(The writer, an alumnus of National Defence College of India, is author of China in India. Views are personal.)

Writer: Abhijit Bhattacharyya

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Learnings from World War I

by Opinion Express / 01 August 2019Nikolay Kudashev, Russian Ambassador to India, says that the history of World War I teaches us many universal lessons, which are still relevant

As the world marks the 105th anniversary of World War I (1914) and remembers the beginning of the war, we recall how it led to an implosion of great empires — Russian, German, Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian — devastated the European continent, drastically reshaped the erstwhile global order and ushered in a period of instability, which finally resulted in the outbreak of the second World War in 1939.

Russia, during the time, was not prepared to enter the war. Nevertheless, when Saint Petersburg’s sincere diplomatic efforts to prevent the conflict failed, Russia completely carried out its commitments to the allies — Serbia, France and Great Britain.

On August 1, 1914, Germany had declared war on Russia. Within the next few days, France and Great Britain were drawn into the warfare. In no time, the Reichswehr was beating against the gates of Paris. St Petersburg took up the ally’s call to attack the opponents immediately and thus began the fateful offensive in Prussia. The subsequent crush of the advancing army, led by General Samsonov, was the price that Russia had paid for saving the French capital — the sacrifice that Supreme Allied Commander, Ferdinand Foch himself had admitted.

That was indeed the first but not the last instance when Russia had come to the allies’ rescue. In 1916, after suffering a number of setbacks, it launched a large-scale assault, led by General Aleksei Brusilov, supporting French efforts. Soon Russia had reacted to a request from the French for help by sending in 45,000 troops to the Western front, where they stood against the Germans alongside with the Indian Cavalry Corps.

Overall, the Russian entry into the war prevented the early rout of the Western allies, thus forcing Germany and Austro-Hungary into a warfare they were doomed to loose.

In 1914, German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish armies lost more than 10 lakh troops at the Russian front while lost 9.8 lakh at the Western and Serbian fronts. In the course of the war, the Germans and the Austrians deployed almost half of their troops against Russia.

After the break out of hostilities, St Petersburg concentrated on strengthening the bonds within the Entente, isolating the Triple Alliance, searched for new allies, worked on future settlements, but was unable to reap any of the benefits. A war period of two and a half years led to an overstrain of Russia’s economy, breakdown of its army, a series of political turmoils, collapse of its monarchy, the 1917 October Revolution and the civil war.

The history of the World War I teaches many universal lessons, which are relevant even today. One of the most important is that of inadmissibility of imposing one’s own sense of exceptionalism upon others with blind use of force. It reminds us of tragic consequences of excessive ambitions of political leaders as well as of importance to firmly uphold the hard-won principles of sovereign equality of states, non-interference in their internal affairs and collective methods for settling crises by political and diplomatic means.

(The writer is a senior journalist)

Writer & Courtesy: The Pioneer

The US-Pak connection

by Anil Gupta / 31 July 2019Though the present US-Pak bonhomie is Afghan-specific, India will have to be watchful and tread its path carefully in case Khan succeeds to placate the Taliban

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan’s recently concluded three-day visit to the US and his one-on-one meeting with US President Donald Trump have evoked mixed reactions in India not only due to the latter’s controversial statement but also due to a lukewarm concern displayed by American authorities with regard to terrorism. Relations between Pakistan and the US have been strained ever since the Trump Administration assumed power due to Islamabad’s support to the global jihadi terrorist organisations and its involvement in cross-border terrorism in India and Afghanistan. Though Pakistan’s involvement in cross-border terror in Iran is also well established, the US does not show much concern due to its strategic concerns in the Gulf region.

Pakistan’s continued support to the Taliban and the Haqqani network operating in Afghanistan irked the new US Administration, which put it on notice, threatening to suspend all aid, including the package to its Army. Islamabad failed to read the US’ intent. In the past, it got away playing the nuclear card. The Western world, particularly the US, is scared of the nuclear arsenal falling in the hands of jihadi terrorists operating from Pakistan’s soil and succumbed to its black mail, dishing out doles to it. Trump, however, is different.

“The US has foolishly given Pakistan more than $33 billion in aid over the last 15 years and they have given us nothing but lies and deceit, thinking of our leaders are fools. They give safe havens to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help. No more!” — this is what Trump tweeted on the first day of 2018. Pakistan went to the extent of blaming Trump for “flinging accusations at Pakistan,” as he was disappointed at the “US’ defeat in Afghanistan.” Trump responded by blocking American aid of approximately $3 billion that also included the $300 million for the Pakistani Army. The Army-to-Army contact between the two nations was suspended. It was a big setback for Pakistan, which was already going through an economic crisis. Islamabad did try to put up a brave front initially but its dwindling economy, India’s diplomatic offensive in exposing Pakistan, the firm stand of the US Administration and the strictness of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) compelled the Imran Khan Government to take stern measures against the terror industry. Whether these measures are a “show window” to win the trust of Trump and the US authorities (a prelude to Khan’s visit to the US) or is there a sense of seriousness or permanency, only time will tell.

Meanwhile, the US has begun preparations for the next presidential election and Trump has also thrown his hat in the race. He is desperate to have one major diplomatic victory about which he can boast to the American people. His initiative in the Korean Peninsula is not making much headway. The strained relations with Iran are harming him more than helping him boost his image. His high-handed tactics of dealing with other countries have got him more enemies than allies. Both China and Russia also have tense relations with America. Although India is likely to be granted the status of the most-favoured non-NATO ally and is already designated with special STA-1 status, the relationship between the two countries is blowing hot and cold. Many in India perceive the US as a fickle ally. In a nutshell, Trump has more negatives to his credit than positives as far as foreign and strategic relations are concerned. He is desperate to win the Afghan tangle, which is not possible without placating the Taliban. The US also knows that only Pakistan can exert the desired influence on the Taliban. This forms the background of Khan’s visit to Pakistan as far as American perspective is concerned and unblocking the US aid.

Let’s first discuss Afghanistan. India has emerged as a major soft power in Kabul and has a big stake in whatever final settlement takes place. The Taliban has been recognised as the key impediment to the end of conflict in Afghanistan. Earlier, India was elbowed out of the direct negotiations with the Taliban, as claimed by a section of the media. To my mind, it is a deliberate decision by the Government to stay away from direct negotiations with the terror group due to adverse ramifications back home. India, however, cannot be ignored. Sooner than later, we will be involved in the final settlement. India remains steadfast on its traditional position of supporting only an “Afghan-led, Afghan owned and Afghan controlled” process, which includes the duly elected Government in Kabul.

With Pakistan forming a key partner in Trump’s South Asia strategy for achieving a political settlement in Afghanistan; defeating Al Qaeda and IS-Khorasan; providing logistical access for US forces and enhancing regional stability, it certainly has gained an upper hand. That is why Pakistan was included for the first time in the trilateral consultations with Russia, China and the US on the Afghanistan peace process held in Beijing in July.

The entire focus of the US was concentrated on Afghanistan during Khan’s visit, which included the Pakistan Army Chief and the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) chief in the entourage. While Khan has agreed to work with Trump to prod the Taliban to strike a peace deal with the aim of extricating the US Army from its longest war, the latter has dangled the offer of unblocking $3 billion aid to Pakistan if Khan succeeds. Khan said, “I want to assure President Trump, Pakistan will do everything within its power to facilitate the Afghan peace process. The world owes it to the long-suffering Afghan people to bring about peace after four decades of conflict.”

There is no doubt that the US is desperate to exit from Afghanistan but is the negotiation with the Taliban the best solution? The terror organisation has not been reformed and its five-year brutal rule is still fresh in the mind of the Afghans. It certainly suits Pakistan because this will help it achieve its aim of achieving strategic depth and the use Afghan territory to promote terrorism. It will also end the hope of a democratic Afghanistan, disappointing millions who are holding out still for a brighter future. India must, therefore, press for its involvement in the peace talks and ensure that the Taliban does not elbow out the elected Afghan Government. Trump’s desperation can be gauged from this statement, “I could win that war within a week, and I don’t want to kill 10 million people. Afghanistan could be wiped off the face of the earth. I don’t want to go that route.”

India has lot at stake because Afghanistan holds significant economic, security and strategic implications for it. We cannot be a mute spectator and have to ensure that democracy survives in Afghanistan. As far as counter-terrorism is concerned, not much time was devoted to the same possibly to avoid public embarrassment to the visiting premier, whose services are badly needed by the US in view of its leverage over the Taliban, thanks to the safe havens it provides to the group’s leadership. But as admitted by Khan himself, with more than 40 terror groups existing in Pakistan, the situation is very fragile. Any terror attack in Afghanistan or India with mass causalities with proven links to Pakistan will reverse the new-found relationship between the US and Pakistan. The latter will have to tread the path very carefully.

Khan was successful in raising the Kashmir issue during the one-on-one meeting with President Trump. It was a spin-doctored question asked by a correspondent to prevent difficult questions on Pakistan’s involvement in terrorism, which would have caused a lot of embarrassment to Pakistan. The question successfully diverted the topic to Kashmir, when Khan lost no time in seeking Trump’s mediation and assistance in resumption of Indo-Pak dialogue. India has made its stand very clear by stating that talks and terror cannot be held together.

Trump surprised everyone with his signature trademark off-the-cuff remark. He has developed a habit of speaking or tweeting without preparation or proper briefing. His remark stoked a controversy, to which New Delhi reacted promptly and set the record straight. Fearing a strain in Indo-US relations, a number of American bureaucrats and leaders also jumped in to save the situation from worsening. But Trump is Trump and his remark should be seen in the light of his desperation for an early Afghan exit.

But Khan has succeeded to once again to internationalise Kashmir after numerous failed attempts by past Governments. India has to be careful and thwart the ISI’s design to portray home-grown terror groups in India by promoting the proxies of IS like ISJK, Al Qaeda like Ansar Ghazwa-ul-Hind, Hizbul Mujahideen and other IS-affiliate/inspired terror outfits. The ISI will certainly attempt to influence Left-wing extremism as has been exposed by the Pune Police disclosing links between urban Naxals and HM.

Khan’s attempt at reviving bilateral trade, as was evident from the large number of businessmen and traders that formed his entourage and unblock the US aid, has failed for the time being and is in no way going to help him to come out of the current economic mess. It may force him to persist with various counter-terrorism mechanisms put in place, including the arrest of Hafiz Saeed. More arrests are likely provided the Army and ISI permit. The imminent danger of being placed in the blacklist by the FATF may tie the hands of the ISI and Army. So the axe is likely to fall more on Afghan-specific terror groups like the Taliban and the Haqqani network.

The visit has been significant as far as bilateral security cooperation and military-to-military relations are concerned. There is a bright chance of resuming suspended military training programmes for Pakistan. At one point during President Trump’s meeting with Khan, the former also hinted at resumption of the security assistance for Pakistan depending on what both countries achieve concerning Afghanistan. The major plus point was the personal rapport established between the two. There is a great likelihood of a direct tele-line between the two leaders to further cement their bonhomie and smoothen any bureaucratic hiccups that may erupt. Islamabad would like to use such an opportunity to sort out other issues in the bilateral realm.

Will there be a change in the Indo-Pacific strategy of the US? Will Pakistan succeed in elbowing out India from the US equation in the region? Indian diplomats will have to work hard to ward off any such possibility. Though the present bonhomie between the two is Afghan-specific, what shape it takes in the future in case Khan succeeds to placate the Taliban, will have to be watched carefully.

(The writer is a Jammu-based political commentator, columnist, security and strategic analyst)

Writer: Anil Gupta

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Temporary Flirtation

by Bhopinder Singh / 27 July 2019If history is anything to go by, it is premature for either the US to trust the Pakistanis or vice versa. Both nations have been known to ultimately succumb to their basic instincts. Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan has been walking the tightrope of the genealogical and evolutionary compulsions that characterise his nation. His jazba (passion) of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) had stormed the elections in 2018 and promised an idyll that is historically, Constitutionally and practically undeliverable – a “Riyasat-e-Madina”, where all citizens are equal in the eyes of the law with guaranteed full fundamental rights.

Acknowledging the enormity of his promise and reset, he instinctively suggested reconstructing the edifice of Pakistan and rechristened it as “Naya Pakistan.” The inheritance of an economy in slide with rising debts, falling currency, inflation and depleted coffers had him scurrying to the Arab capitals, Beijing and even to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This to impress upon them an economically-prudent, austere and reformist agenda that would no longer be profligate or reckless with the sanctioned “aid.”

This entailed the toning down of his anti-IMF tirade that he had invoked during the pre-election campaigning, as indeed, personally chauffeuring the all-important Princelings from the rival camps of Saudi Arabia and Qatar. While money has started trickling in bits, it has extracted a severe price from the common citizenry as they reel under spiralling price rises and shortages.

The onerous task of re-setting to “Naya Pakistan” essentially implies the reneging of various Pakistani positions. The opening act of the tenure was lavish in promising such change, including the famous “If India takes one step, Pakistan will take two.” The optics and soundbites emanating from the prime ministerial house were in conformity with the naya way of things and soon the usual ostentatiousness was frowned upon and the all-powerful razzmatazz was supposedly cut.

The world at large waited with bated breath to figure out if it was yet another exercise in political posturing or if Pakistan had indeed evolved to the portents of “Naya Pakistan.” But the cracks showed up almost immediately as Imran Khan succumbed to the nation’s ingrained bigotry and dropped the economist, Atif Mian, from the economic advisory, apparently on account of his belonging to the minority and the persecuted Ahmediya faith.

From the Indian perspective, Imran Khan continued making naïve statements against terrorism while the Pakistani incorrigibility continued in Afghanistan. Then the Pulwama episode happened. The trust deficit between Pakistan and all its irate neighbours (India, Afghanistan and Iran) widened. A certain disillusionment against the built-up hype of “Naya Pakistan” started afresh.

The US was already breathing down Pakistan’s neck for its duplicity and US President Donald Trump famously tweeted that Pakistan does not “do a damn thing” in return for the billions of dollars in American “aid.” Imran Khan retaliated and tweeted back: “No Pakistani was involved in 9/11 but it decided to participate in the US’ war on terror” and added, “Pakistan suffered 75,000 casualties in this war and over $123 billion was lost to the economy.” US aid “was a minuscule $20 billion.” The free-for-all between Pakistan and the US ensured that Islamabad swung even more sharply towards the willing arms of Beijing and almost started behaving like a beholden and vassal state of China.

Providentially, for Imran Khan and Pakistan, the whimsical Trump, who had ranted against the Pakistani establishment, had a re-think on his Afghanistan strategy and realised that he would need the services of its bête noire ie, Pakistan, in extricating itself out of the mess in Afghanistan.

In a move reminiscent of dumping Afghanistan in the lurch after ensuring the Soviet-withdrawal from Kabul, the US is yet again working towards a similar vacuum; with Pakistan rubbing its hands in glee. Suddenly, Islamabad is back in favour as all is seemingly forgotten and forgiven and Imran Khan is back to reverse-swinging his “Naya Pakistan” with revised gusto — this time in Washington, DC.

Both Pakistan and the US are masters of selective amnesia and their dalliances of the past, which included flying and feting of the Afghan mujahideen to the White House and supporting these warlords with weapons, have become a lost memory. Both Imran Khan and Trump now shake hands and the former thanks to the Presidents of the United States of America (POTUSA) with “his understanding of Pakistan’s point of view!”

The incredulity continues with Imran Khan promising, “I want to assure President Trump, Pakistan will do everything within its power to facilitate the Afghan peace process” — a rote statement that has consistently and unfailingly been dishonoured by Pakistan.

The hapless Afghan regime of Ashraf Ghani looks on with shocked bewilderment and New Delhi is left having to deal with Trump’s creative memory of Prime Minister Modi apparently asking him to mediate in Kashmir!

The US President’s statements were rightfully, strongly and unequivocally slammed by New Delhi as outrightly incorrect and the same got acknowledged by other functionaries at the Capitol Hill. However, Imran Khan persisted with his façade of “surprise” at the Indian response to “Trump’s offer of mediation” as he feigned ignorance at India’s unwavering and consistent stand on a bilateral framework on Kashmir.

Today, Imran Khan is on a charm offensive both domestically (flying commercial) and internationally, staying at his Ambassador’s residence to avoid “unnecessary expenditure.” Trump has added one more to his embarrassingly long list of documented inexactitudes, which now “exceed 10,000.”

Both the US and Pakistan are again in a convenient and tactical huddle that suits their individual and topical urgencies, without bothering about the past, present or future with such tenuous underpinnings. Beyond the reality of US-Pakistan sparring openly, just a few months back, this region has not forgotten the murky history of American hand in the bloodshed of the 1980s during the height of the Cold War or indeed in India with the US’ seventh fleet sailing menacingly towards the Bay of Bengal in 1971. It would be premature for either the US to trust the Pakistanis or vice versa as history suggests that both nations ultimately succumb to their basic instincts and while India, Afghanistan and Iran will lick their wounds for now — the “deep state” within Pakistan will ultimately rear its head and both Trump and Khan will end up looking like their predecessors.

(The writer, a military veteran, is a former Lt Governor of Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Puducherry)

Writer: Bhopinder Singh

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Can Boris Johnson delivers?

by Opinion Express / 26 July 2019Boris Johnson has been appointed British PM by the Conservative Party. Can he deliver on promises?

It appears that to be a successful populist leader in the English-speaking world, you need to conjure up a cool acronym. Donald Trump’s mantra in the 2016 elections was to ‘Make America Great Again’ or MAGA. And now that Trump’s ‘friend’ Boris Johnson is in 10, Downing Street, the home of the British Prime Minister, he has come up with the slogan ‘DUDE’ to outline his objectives. Those are to ‘Deliver Brexit’; ‘Unite Britain’; ‘Defeat (Jeremy) Corbyn’ the leader of the opposition Labour Party and lastly to ‘Energise the nation’, the final one coming because, as Johnson himself noted in his acceptance speech, ‘DUD’ doesn’t make for a great tagline. One could argue nor does ‘DUDE’ which sounds more like something a college student would say rather than a 55-year old shaggy-haired populist whose insurrection doomed the government of his predecessor Theresa May. Those who know Johnson, and thanks to his past as a journalist in major British newspapers, have said that being Prime Minister was his ultimate ambition. But make no mistake, he might fashion himself as a populist but is a product of Britain’s upper classes, much like Donald Trump is a product of the New York elite. And Johnson has the extremely difficult task of uniting the nation and delivering Brexit at the same time. He has taken the hard line stance that a ‘Hard’ Brexit, that is the British exiting the European Union (EU) without any sort of a deal, come what may by October 31. There are several problems with this stance expected to cripple trade and cause major issues on Ireland, which remains divided between the British North and the Republic of Ireland. His tactic of negotiating with a gun to his head with the EU looks suspiciously like Pakistan’s negotiating tactics.

But the question is will ‘BoJo’ change now that he has the top job? Previously he held the high-profile role of Mayor of London where he managed to be re-elected as a Conservative in a Left-leaning city. A floppy-haired “likeable rogue”, whose private life still makes headlines, he was pro-migrant, pro-LGBT rights and even pro-Europe. Some are hoping that BoJo will now take a turn and manage to deliver good governance, especially since he is by far and away Britain’s most popular politician. But with just about a 100 days to go before Brexit, no matter which sort, he has an unenviable task in front of him. And clever acronyms which might make you an entertaining writer does not make one a statesman.

Writer & Courtesy: The Pioneer

Can Trump be defeated?

by Opinion Express / 22 July 2019As the campaign for the US presidential elections, slated for November 2020, heats up, can the man be defeated?

Much newsprint has been wasted by commentators doubting US President Donald Trump’s intelligence or his methods, particularly his single-minded determination to keep Twitter relevant in foreign ministry offices and corporate headquarters across the world, let alone American homes. Yet one must admit he is a smart man. You do not win the US presidency against an establishment candidate after securing your party’s candidacy in a crowded field. Trump’s upending of the global trade paradigm has been drastic but he does make some sense when it comes to domestic priorities. But his latest statement against a few American Congresswomen from the Democratic Party, telling them in no uncertain terms that if they do not “love America” they should go back to where they “came from,” is distressing. It just so happens that Ilhan Omar, one of the Congresswomen attacked by Trump, is of Somalian descent and this is nothing more than Trump catering to the nativist part of the American electorate. Instead of reaching out to minorities, who are unlikely to vote for him, he is trying to energise his base. So the “Lock her up”, Trump’s slogan against Hillary Clinton, has been intensified now with his supporters chanting, “Send her home” about Omar.

Trump has been pilloried by political rivals. The Democratic Party, fractured by a contentious primary election to select the man or woman who will contest against him, has backed Omar and her fellow Congresswomen. Even foreign politicians have attacked him, particularly from Europe. Yet, Trump’s attack resonates as nativist forces in the US look on immigrants as interlopers in their nation, ignoring that immigrants have actually been change agents. But with few of Trump’s Republican allies attacking him, he will carry on this path and his cries against immigrants will get stronger. It remains to be seen if the Democratic Party can put up a credible candidate who can stand against Trump. The risk they run, like several other liberal parties across the world, is that they might put someone from the extreme-left ideological wing of the party who will stand little chance against Trump’s intelligence. Some say Trump was a failure in everything that he did, his business ventures have never been as successful as he claims. But looking at him now, it is impossible to see how he is anything but a winner.

Writer & Courtesy: Pioneer

Intersecting conflicts between Israel and Palestine

by KK PAUL / 18 July 2019The state of action and reaction between Israelis and Palestinians has continued for decades with several wars in addition to local level intersecting conflicts

It is perhaps for the first time since the Sadat-Begin accord presided over by Jimmy Carter 40 years ago that the US last month announced a very laudable and a concrete proposal for the development and mainstreaming of Palestinians. Worth over $7 billion, the plan was unveiled at a recent conference in Bahrain by Kushner, the son-in-law of US President Donald Trump. Though the Palestinians did not attend, some Israeli private entrepreneurs were present. For the present, without an official Israeli approval, it is difficult to visualise any forward movement towards the implementation of such a proposal, which made virtually no contribution towards ending the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

To the current generation of youth, Islamic terrorism is synonymous with images of 9/11, Osama Bin Laden and ISIS. To their parents, it would be the Munich Olympics massacre, a violent Beirut and numerous hijackings. Research papers and books have been written to theorise that Islam is a manifestation of a violent civilisation and its interface with other religious communities bristles with faultlines. While this may be only true in certain specific instances and not as a generality, at the same time it would be important for us to understand the genesis of violence involving Islamic groups in the contemporary scene. For this we have to go back in history by about a hundred years.

When Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb, assassinated Archduke Francis Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, a series of events was set in motion leading to the World War I and the subsequent collapse of the Ottoman and other empires. After the war, this resulted in uncertainty for Syria, Palestine, Egypt and Algeria, countries which had been conquered 400 years ago for the Ottomans by Selim I. Later, under the aegis of the League of Nations, a permanent Mandate Commission was constituted, which allowed certain countries to be administered by those who had won or occupied such territories. Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq and Algeria, all parts of former Turkish Empire, were classified as category A mandates, which were entitled to eventual independence. The administration of Iraq, Palestine and Egypt was handed over to Britain while Syria and Lebanon were awarded to France. Keeping in line with the spirit of the mandates, Iraq became independent in 1937.

At this stage it is important to recall that while the war was still raging, in November 1917, then foreign secretary of Britain, Arthur James Balfour wrote to Baron Rothschild, head of an English Jewish banking family, pledging British support to Zionist efforts for establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. This was a war-time communication known as the Balfour declaration, conveying an intent on future policy in order to win over the Russians, who were at that time under the influence of Jews, for their greater involvement in the war effort as at that time Kerensky was playing a very dominant role in the government. Later, however, with the success of the Russian revolution, also in November 1917, the ground situation changed drastically as Lenin declared an armistice with Germany unilaterally. Nevertheless, the British promise remained intact.

Even though the administration under the mandate was in the hands of Britain, Jews from all over the world began to make serious plans and efforts to start administering the Palestinian territory sometime in future. This led to heavy influx of Jews into this area. Despite the fact that some of these areas were in an active theatre of World War II, the hardliners wanted the mandate to be circumvented as quickly as possible. The obvious aim was that when Palestine would be ripe for independence and the British left after the completion of the mandate, it should become a Jewish territory. In due course, such hardliners began a campaign to harass the British so that they were compelled to vacate Palestine sooner than later. In this context, the activities of the Irgun and the Stern gangs, both Jewish terrorist outfits, are worth recalling.

Their campaign began in November 1944 when the Stern Gang assassinated the British Minister for the Middle East, Lord Moyne, in Cairo. This was followed by an escalation of violence in Palestine, with several incidents against the British. In the absence of any clear directions on policy, the British chose not to respond. But when Irgun launched a wave of attacks, bombing trains and bridges connecting Palestine to neighbouring states, a response came swiftly. Mass arrests were made across Palestine and over 2,000 Zionists were arrested. However, none of the ring leaders of Irgun or Stern Gang was caught. This resulted in escalation of violence with Irgun inflicting a devastating blow to the British rule in Palestine when it bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. As is well known, this bombing was planned by the leader of the Irgun, Menachem Begin, later to be the sixth Prime Minister of Israel and a joint winner of a Nobel Peace Prize for the 1978 Arab-Israel accord.

Begin, in his book The Revolt, has explained “history and experience taught us that if we are able to destroy the prestige of British in Palestine, the regime will break. Since we found the enslaving government’s weak point, we did not let it go.” After the success of this bombing, the Irgun and the Stern Gang extended their activities outside Palestine. An Irgun cell bombed the British Embassy in Rome and followed this with a series of attacks on British targets in Germany. Later, Irgun bombed a club in London, injuring several servicemen. Prominent British public figures connected with Palestine also received death threats. In June 1947, the Stern Gang launched a letter-bomb campaign in Britain, which targetted prominent member of the Cabinet. Sir Stafford Cripps barely escaped becoming a victim. Similarly, Sir Anthony Eden was lucky to have escaped. There was no counter from the British, much less from the Palestinians, as the British by then, had almost made up their mind to quit the mandate.

Ultimately the strength of the Jewish activists, with support of influential Jews from all over the world and amply demonstrated by its armed struggle in Palestine, persuaded the United Nations in November 1947 to partition Palestine into separate, independent Jewish and Arab states. This led to a virtual free for all and a war-like situation between various competing factions from which Israel emerged as a viable State, while Palestine ceased to exist. The Palestinian population, largely leaderless and ill-prepared for war, was driven out of what became Israeli territory by a combination of deliberate attacks. When the war ended, Palestinians had been reduced to a refugee status and kept in camps. Not surprisingly, this gave birth to a new generation of insurgents, who later turned to the same methods that Jews had used to drive out the British. This was the birth of the PLO.

The seeds of terrorism had been sown with the tree growing rapidly with several branches of varied shades. Some were taken over by the Left wing revolutionaries nurtured by the Cold War politics. On the other hand, we had a nation state fighting for its existence, security and sovereignty. This state of action and reaction between Israelis and Palestinians has continued for decades with several wars in addition to local level intersecting conflicts. In the mean time, the politics of Islamic dominance, Gulf and Middle East oil, besides the super power rivalries and their attempts to ensure through surrogates that their sphere of influence remains strong and intact, has kept the pot boiling. This has had consequences for the world which have been serious and long-lasting. The fallout from this insurgency of eight decades ago is still playing out on the local, regional and world stages in different forms by different players.

(The writer is a retired Delhi Police Commissioner and former Uttarakhand Governor)

Writer: KK PAUL

Courtesy: The Pioneer

Muslim Brotherhood in the Egyptian State

by Nadeem Paracha / 05 July 2019Former president Mohammad Morsi’s tragic death in captivity has once again highlighted the tense relationship of his Islamist party and the Arab World

The sudden death of Mohammad Morsi, Egypt’s first elected Prime Minister, who was overthrown in a military coup in 2013 and was facing trial for various charges and a 20-year sentence, has once again brought the international media’s focus on the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) — the party Morsi was a member of. The MB was not a new party that had emerged from the rumblings of the so-called “Arab Spring” in 2011 — an uprising that saw the toppling of a number of authoritarian regimes across the Arab world. It was, and still is, one of the oldest mainstream “Islamist” outfits in the Middle East, which succeeded in coming to power in Egypt in 2012 through a general election.

The MB members also managed to win the largest percentage of votes — 37.4 per cent — during the 2011 Tunisia election as the Ennahda Party. Turkey’s Justice & Development Party (AKP), which has been winning elections since 2002, is often understood to be the Turkish version of MB. According to Fait Muedini’s The Role of Religion in the Arab Spring, the MB only played a “limited role” during the Arab Spring. Muedini writes that MB didn’t want to overplay its “Islamist” credentials during the unrest, which could have made it convenient for the state and Government in Egypt and Tunisia to denounce the uprisings as “Islamist.” This way, the protests may have lost international support.

As the ruling parties weakened and disintegrated during the protests, new parties emerged, but they were not as organised as the MB. Over the decades, the MB had established widespread political and social networks, which helped it win the largest number of votes during the first post-Arab Spring elections in Egypt and Tunisia. Professor Edip Asaf of Istanbul University writes in an essay that the MB looked towards Turkey’s AKP “as an example”. He echoes French political scientist and author Oliver Roy’s assertion that the AKP’s “Turkish model” became popular among Islamic outfits such as the MB in their bid to become part of the political mainstream, without overtly flexing their “Islamist” muscle.

Refuting the influential American academic Samuel Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilisations’ hypothesis — which could not find any cultural or political common ground between the ‘authoritarian Muslim world’ and the democratic West — the AKP and the MB responded with a new paradigm: Clash within civilisations. This differentiated between moderate, democratic Muslim forces and the radical and reactionary ones.

According to this paradigm, the friction and tension within the Muslim world (between the moderates and the radicals) had produced political phenomena such as Turkey’s AKP and later, the democratic coming to power of the MB in Egypt and the Ennahda Party in Tunisia. These were Islamic outfits, who agreed to become inclusive, and focussed more on addressing economic issues rather than on the imposition of religious laws.

But the AKP had evolved in a staunchly secular Muslim republic. The many movements, which preceded the formation of the AKP, were non-militant and accepted the principles of Turkish nationalism, established during the formation of the modern Turkish republic in 1923 by Ataturk.

Even though the MB had decided to let go of its militant tendencies in the 1970s, it could not entirely alter the perception that the party remained rooted in the ideas of one of its most celebrated heroes, Sayyid Qutb, who was executed in 1966 for allegedly plotting the assassination of the then Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Interestingly, the MB was established in Egypt in 1928 as a movement inspired by Muslim Modernism and Pan-Islamism. Muslim modernism had been developing ever since the mid-19th century as a way to address the rise of European colonialism through the adoption of modern sciences and economics. Muslim Modernism advocated the readjustment of Islamic traditions and polities through “modernist” tools such as pragmatism, rationalism, science, capitalism and/or socialism.

Pan-Islamism, on the other hand, wanted to do this to help the Muslims gain ascendency in colonial conditions, and once in, dismantle Western colonial supremacy and carve out a modern universal Islamic caliphate. According to Malise Ruthven, in Islam in the World, the MB became more conservative and militant once various reformist ideas of Muslim modernism began being adopted by various non-religious Muslim leaders and outfits.

By the 1940s, the MB was being accused for organising assassinations and bomb attacks against colonial British officials in Egypt and the country’s monarch. In 1948, an MB member assassinated the country’s Prime Minister. However, in 1949, MB’s founder Hassan Al-Banna was killed in a retaliatory strike by Egypt’s secret police.

According to HM Hamouda’s 1985 tome, Secrets of the Movement of Free Officers, the free officers movement, which toppled the Egyptian monarchy in 1952 and ousted the British, was formed within the MB. According to an essay by Selma Botman in the 1986 edition of Middle Eastern Studies, anti-monarchy and anti-British Egyptian officers had used the secret network constructed by the MB to facilitate their attempt to take over power.

However, by 1954, the now-in-power free officers movement clashed with the MB, accusing it of trying to assassinate Nasser. MB denounced the new Government as being “anti-Islam” and “secular.” Hundreds of MB leaders were arrested and jailed.

One such leader was Qutb, an unassuming man, who had joined MB after returning from a trip to the US. Influenced by the writings of controversial French eugenicist and alleged Nazi sympathiser Alexis Carrel — who often attacked Western modernity — and by the prolific South Asian Islamic scholar Abul Ala Maududi, who had described modernity as modern-day “jahiliya,” Qutb advocated an armed social and political struggle against this jahiliya.

Many MB activists escaped arrest and were given asylum by Saudi Arabia. After Nasser’s death in 1970 and Egypt’s restoration of friendly ties with the US and Saudi Arabia, hundreds of MB members were allowed to return to the country. MB decided to renounce violence and enter mainstream politics. Disagreeing with this resolution and angered by Egypt’s recognition of Israel in 1979, two groups separated from MB. They insisted on following Qutb’s teachings. One such faction assassinated Egyptian president Anwar Sadat in 1981.

Nevertheless, the MB as a whole continued on its “mainstream” path. But the MB is condemned by its own history. Those who came out to protest against the Morsi regime claimed that, no matter how “moderate” it pretends to be, MB’s end goal remains the enactment of a totalitarian theocracy. The opponents of this view bemoan that the coup against Morsi marked the end of a unique experiment in which a once-militant Islamist outfit was willing to take a more pluralistic and democratic path.

MB’s erstwhile backers, the Saudi monarchy, disagreed. In an environment of monarchy-backed reform within the kingdom, it now sees MB as a dangerous impediment, which can use its vast network across the Arab world to undermine Saudi influence and trigger populist uprisings, including one in the kingdom.

Either MB will look to further modify its course to prove that it is no more a theocratic threat or a democratic ruse, or it may restore its militant tendencies. But I believe the latter is not possible in a world where there will not be a Saudi Arabia or a US welcoming escaping MB cadres from the arm of the Egyptian state.

(The Dawn)

Writer: Nadeem Paracha

Courtesy: The Pioneer

China’s Growing Investment in Nepal Territories

by Claude Arpi / 04 July 2019In other continents, too, nations have to kowtow to China in return for investment and debt funding, though they are slowly waking up to the fact that all is not rosy

China has managed to tame the wild Tibetan yaks, according to Xinhua. “Under the touch of the petite scientist Yan Ping, the tall and powerful black yak, weighing over 400 kg, is as obedient as a lamb,” a report said. The news agency added, “Unlike other yaks, this one has no horns.” Yan, who works for the Lanzhou Institute of Husbandry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, explained, “The Ashidan yak has no horns and has a mild temperament, easy to keep and feed.” How metaphorical this is.

Beijing seems to have developed some expertise in taming humans and nations, too. The Taiwan News reported how “Manila kowtows to Beijing, cedes Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in South China Sea.” The once-wild President of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, is said to have ceded “ground in the South China Sea through an ‘informal’ and ‘undocumented’ [agreement] with President Xi Jinping.” The Taiwanese newspaper noted that many citizens of the Philippines were “already concerned over the Government’s unwillingness to safeguard the territory of the country’s EEZ.” The article concluded that this makes the Duterte Government appear even weaker in protecting the nation’s maritime territory. But it is not only the Philippines, which has been tamed and has accepted Beijing’s diktats. India’s northern neighbour, Nepal, seems to have fallen in the trap, too.

Newsgram, an independent media agency, recently pointed out that it is the Nepal Government in Kathmandu, which forces local journalists to avoid critical reporting on China, the largest investor of the Himalayan land-locked nation. Anil Giri, the foreign affairs correspondent for The Kathmandu Post, told Voice of America that “journalists are discouraged from covering Tibetan affairs to mollify China and that Government officials shy away from commenting on China-related issues. China sponsors junkets for Nepalese journalists and that’s why probably we don’t see a lot of criticism about China’s growing investment in Nepal, Chinese doing business in Nepal and China’s growing political clout in Nepal.”

The lamb-lamb attitude in Kathmandu was clear in an incident that took place recently at the Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu. The Himalayan Times reported: “Man labelled Dalai Lama’s agent, deported to the US.” Apparently, the Nepal immigration mistook a Tibetan called Penpa Tsering, holding a US passport and arriving from America with his homonym as former representative to the Dalai Lama in the US. Nepali officials argued that the man was “on China’s most-wanted list.” In Dharamsala, the former Tibetan representative observed: “It clearly shows that the Chinese Government’s pressure on Nepal is working.”

Nepalese Home Minister Ram Bahadur Thapa affirmed that the deportation was only an act “of honouring the ‘One-China’ policy.” A few weeks earlier, two members of Nepal’s Parliament, Ekwal Miyan and Pradip Yadav, had to apologise for having attended the Seventh World Parliamentarians’ Convention on Tibet, which was held in Latvia’s capital Riga between May 7 and 10, after Beijing pressurised Kathmandu.

In a joint Press statement, the two MPs declared that they “happened to inadvertently attend the conference …due to wrong information …when they were on a private visit to Turkey, Switzerland and Latvia.” They had even given their speeches by mistake! This shows how China can today dictate terms to “small” countries like Nepal.

At the same time, Xinhua proudly reminded its readers that in the summer of 1921, “a dozen of Communist Party of China (CPC) members were forced to leave a small building in the French concession area of Shanghai and boarded a boat on the Nanhu Lake in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, concluding the first National Congress of the CPC. …Since then, the [communist] party has managed to lead a vulnerable country to move closer towards the world’s centre stage.”

The news agency asserted: “The Chinese nation has stood up, grown rich and is becoming strong. …Socialism with Chinese characteristics have maintained stability and vitality in the tide of global changes.”

The Tibetans, who have been tamed more than 60 years ago, are an easy prey. A couple of weeks ago, a Tibetan Minister in the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) in Dharamsala was denied visa to attend a conference in Mongolia. Karma Gelek Yuthok, Minister of Religion and Culture, was to attend the Asian Buddhist Conference in the Mongolian capital, Ulaanbaatar. The Minister could only say that it was “the clearest sign yet of China’s aggressive campaign of undermining core democratic freedoms across the world.”

On the Roof of the World, China has now all the cards in hand to nominate its own 15th Dalai Lama. Gyaltsen Norbu, the Panchen Lama, selected and groomed by Beijing, has been elected as the president of the Tibetan branch of the Buddhist Association of China. Gyaltsen Norbu recently visited Thailand. On his return to Beijing, he affirmed: “We are fortunate to be in the era of the development and the rise of New China and thank the Communist Party of China for leading the Chinese people in achieving the tremendous transformation of standing up, growing rich and becoming strong.”

In other continents, too, nations have to kowtow, though they are slowly waking up to the fact that all is not rosy. The examples of Sri Lanka and the Maldives are often cited, but there are some in Africa too.

The Ethiopian Business Review recently had a cover-story: “Africa falling into debt-trap” while The African Exponent, an online outlet for African news, dared to write: “Horror Awaits African Leaders as China Withdraws Debt Funding.” It explained: “After an impressive run of a good relationship with China, scooping up at least $9.8 billion between 2006 and 2017, making it Africa’s third-largest recipient of Chinese loans, the good ‘friendship’ between the two countries seems to have come to a snag.” The reporter noted that in September, China promised another $60 billion in aid and loans to the continent: “Xi Jinping promised the money would come with no political strings attached.”

But all good things have an end. When Uhuru Kenyatta, the Kenyan President, visited China in May, “the atmosphere that greeted him was unfamiliar to the China of old. Questions were raised about corruption, as well as the figures and sums [that Kenya] had proposed.” Kenyatta did not like it.

The Chinese even wanted to know if he planned to stand for office again in 2022: “It was like talking to the World Bank,” observed an aide to the Kenyan leader. All this, as well as the recent events in Hong Kong, show that the taming of humans or nations cannot be taken for granted; nobody remains a lamb forever.

(The writer is an expert on India-China relations)

Writer: Claude Arpi

Courtesy: The Pioneer

FREE Download

OPINION EXPRESS MAGAZINE

Offer of the Month