Restarting Jet

by Opinion Express / 21 October 2020With only a few details public and no dates set for resuming fights, there is no guarantee that this will succeed

The bid to take over the remaining assets and brand of Jet Airways by Dubai-based real estate entrepreneur Murari Jalan and American private equity firm Kalrock Capital has been accepted by the lenders. Even though they will have to accept a massive 90 per cent haircut on their outstandings from the airline, the fact that they will get something is a lot better than what they faced with Kingfisher. Former employees of the now grounded airline as well as other unsecured creditors, everyone from those who provided taxi and catering services to passengers with tickets for flights that never took off, are hoping that the new management will clear their dues as well. Unfortunately, while the new management might absorb some old employees and even executives, it does not hold any obligation to clear these unsecured dues. The new owners could clear some dues in order to build goodwill but of the estimated Rs 40,000 crore owed by Jet Airways to various creditors and employees at the time it suspended operations in April 2019, much of it will never be seen again.

This deal is being spoken about as a success of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) that was introduced by the Government in 2016. Some even suspect that the Government pushed this deal through to highlight that the IBC can be a success as several other high-profile cases are stuck. That said, the proof of the pudding is in the eating and the proof of an airline is in the flying. With few details public, there are no firm dates on when this ‘new’ Jet Airways can fly again. As the aviation market globally is in the doldrums, one also questions whether this is a smart time to launch an airline when customer demand is less than half of what it was this time last year. Yes, it will be easier than it would have been in February to get slots and even lease new planes but the new management should not have misplaced optimism about “customer loyalty.” Restarting a brand, any brand, and particularly a service brand after a period of not operating is not easy and customers are extremely fickle. And with the likelihood of one, maybe even two airlines in India potentially falling victim to the pandemic, thanks to stretched balance sheets, things might actually get very difficult for the new ownership. That said, we wish them all the best and hope that they can succeed, and hope is a very powerful thing these days.

Mix active and passive investment styles for high returns

by Hima Bindu Kota / 19 October 2020Since market conditions are volatile, an experienced fund manager should have the expertise to switch between both the strategies to satisfy investors

The science of stock market investing has long been a mystery for normal retail investors and there are numerous debates about which strategy is better. There are two divergent ideologies: Active and passive investment. The passive strategy, which is mainly followed by the legendary Warren Buffet, is a long-term one that mirrors a particular index where the returns are generated due to the natural upswing of stock markets, ignoring short-term setbacks and even sharp downturns. The simplest way of embarking on a passive approach is to buy an index fund that follows one of the major indices like the S&P 500, Dow Jones and BSE Sensex or Nifty in India. These index funds automatically adjust their portfolios to any new additions or deletions to the original index in the same proportion. Passive investment is for conservative and risk-averse people who are looking for low-risk investment and are not overly concerned with seeing rapid gains. The idea behind this is the classic value investing style, which looks at long-term benefits of holding on to undervalued stocks with huge future earning power.

Active investing, on the other hand, aims to generate above market returns by an in-depth research and analysis and using the knowledge and expertise to manoeuvre into or out of a particular stock, bond or any asset, taking full advantage of short-term price fluctuations. Since it does not necessarily mimic any index, it provides the flexibility of buying stocks which could be hidden gems. Since active investors are not stuck with index stocks, they are able to exit any sector or stocks when the risk becomes too high and can also hedge their bets using various techniques such as short sales or put options. However, all the research overheads and frequent buying and selling make active investment very expensive. It is also a highly risky affair since higher returns can only be expected when the going is good but things can go terribly wrong during market downturns and therefore, due to its volatile nature, the active investment strategy is better suited for people who are aggressive and risk-tolerant. In passive management, one rises and sinks with the ship whereas actively managed funds have the ability to provide greater opportunity for profit, albeit, increasing the risk. According to researchers who propagate the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), stock markets are efficient in nature and, therefore, actively managed funds cannot outperform them over a long period of time.

So does active portfolio management create value? The debate about the merit of active vs passive portfolio management is supported by numerous researches worldwide. In the mid-1960s, Eugene Fama adjusted the EMH and suggested three forms of informational efficiencies; the weak form, semi-strong and strong. This hypothesis suggests that investors cannot beat the markets by actively managing portfolios, as stock markets incorporate all the publicly available and privately-held information into price movements. Therefore, fund managers cannot beat the stock markets and generate higher returns on a long-term basis. This theory is supported by many researches. In 1966, Treynor and Mazuy studied the performance of 57 mutual funds and their sensitivity to market fluctuations and concluded that maybe, no investor, professional or amateur, can outguess the market. A similar study in 1968 by Jensen found that average mutual funds produced low returns. In a study to understand the importance of selecting a good fund manager, Dunn and Theiser in 1983 found that there is only a 50-50 chance that an active fund manager can produce better returns than the bourses. This was reiterated by the Nobel laureate, Sharpe, in 1991 who showed that active fund managers cannot give better returns than passive investment strategies, mainly due to active management being expensive.

That brings us to the question, can anyone predict the stock market movements and earn abnormal returns? Nobel laureate Samuelson quotes Aristotle in explaining this, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” This means that an investor cannot do better than the bourses. Sharpe explains this on the basis of costs and says since both active and passive management generate equal returns before costs, active management loses as it is costlier, and therefore generates less after-cost returns.

Modern portfolio theory assumes that all market participants are rational in their investment behaviour and invest only in stocks at their fair value. However, in reality, the markets consist of various investors who are driven by different emotions, impulses, experiences, risk tolerance, timelines and legal constraints. Since efficient market hypothesis presumes that all available information is reflected in the stock process accurately and timely, no investor can earn abnormal returns. They can, of course, earn normal returns, which are the market returns. This assumption is used as an excuse by people who have faced losses during any meltdown, as they take a break in using their prudence, creativity and perception to invest. But there is always a gap between theory and practice. The question now arises: Are stock markets efficient? Do they reflect all available information accurately and timely? There is evidence that market efficiencies may be lower in emerging markets that can give a chance to active fund managers to find arbitrage opportunities. After the 2008 financial crisis, the developed world has focussed on emerging markets, which have risen as engines for global growth, driven by younger populations, higher consumption levels, modernisation of infrastructure and integration with the world economy. According to UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2019, FDI flows to developing economies rose by two per cent to $706 billion in 2018. Developing Asia, already the largest recipient region of FDI flows, registered an increase of four per cent to $512 billion, with positive growth occurring in all sub-regions. China attracted $139 billion, an increase of four per cent. Flows to South-East Asia rose by three per cent to $149 billion, a record level. This increase is for the third consecutive year. FDI flows to Africa expanded by 11 per cent to $46 billion. Emerging markets, being informationally inefficient, may provide opportunities for excess returns and portfolio diversifications through market timing and stock selection.

A study by Kremnitzer shows that actively managed mutual funds outperformed passive ones. The researcher, using data from TD Ameritrade Research and the Standard and Poors NetAdvantage database on all existing US mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs), dedicated to emerging markets, found that the before tax returns of actively-managed mutual funds yielded superior returns of approximately 2.87 per cent over passively managed ETFs. So, which investment style should be chosen? An apt strategy could be to combine both active and passive investment styles, depending on the stock market conditions. Active fund management could be especially beneficial when stock markets are volatile. Passive fund management is a better strategy where the stocks and markets are highly correlated and move together.

Ultimately, it comes down to personal priorities, timelines and goals. An experienced fund manager should have the expertise to switch.

(The writer is Associate Professor, Amity University, Noida)

Give MSMEs a competitive edge through IT infra

by Priya Gupta / 14 October 2020If we want to develop the ‘Made in India’ brand and compete globally, we have to upgrade all systems of manufacturing and services

Knowledge is the key to success. This has been proved time and again by the achievements of start-ups. In almost all fields, new businesses have not only challenged market leaders but also undercut them. Unicorns like Paytm, PhonePe, Flipkart, Netmeds, MakeMyTrip, OYO did not create a new market but rearranged the existing one and became leaders. A similar approach is needed in the manufacturing sector if we are keen to take on the world and are dreaming of becoming a $5 trillion economy.

The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) sector is key to the Indian economy as it is one of the biggest job generators. It has also created resilience to withstand global economic shocks and turmoil. With around 63.4 million units throughout India, MSMEs contribute to around 6.11 per cent of the manufacturing Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 24.63 per cent of the GDP from service activities, as well as 33.4 per cent of the manufacturing output. Their export share is 40 per cent. The MSME sector is the second-largest employer after agriculture, giving jobs to more than 120 million people in rural areas. MSMEs are now contributing close to 15 per cent to the overall GDP of India.

If the Government wants to support MSMEs and equip them to meet global standards — as in the current scenario we are not only working to “Make in India” but also trying to “Make for the World” — we need to upgrade them in all aspects: Infrastructure, technology, manpower and capital. Plus, in addition to financial and logistics support, MSMEs need information technology (IT) support to upgrade themselves. They can be carriers of knowledge and experience and create a repository for others.

To match international standards and compete globally, upgraded IT infrastructure is needed for MSMEs and if the same is provided by the Government free or at reduced costs, then it will take a huge financial and operational burden off small entities.

In the current scenario, skilled manpower will be a challenge for MSMEs and with shared IT support, they can reduce their dependence on internal staff. Another big challenge in front of MSMEs will be limited budgets for upgradation of their existing IT infrastructure and affordability of operating costs. The requirement of research and development in MSMEs is different from that of big industries as they need cost and resource efficient solutions. MSMEs need continuous upgradation to compete globally and benchmarking is required so that they can produce world-class goods. Big industry players, who are cash-rich, always upgrade by deploying huge capital and beat small competitors like MSMEs.

By introducing shared IT infrastructure from the Government’s side, MSMEs can save on capital expenditure and operating costs, giving them better profitability. Owing to the nature of their business and size, most MSMEs don’t use a high level of IT support and lack badly in IT infrastructure. As these are promoter/owner-driven and focus more on their core job, their investment in core job IT and research is always lacking.

For example, a small auto-component manufacturer requires designing software to improvise designs or to reduce cost. New software could cost the business Rs 5-8 lakh, which is unaffordable for most. By using shared IT services, the manufacturer can improve the design, control quality and deliver a better product under stringent cost control. Such a requirement can be very diverse, starting from basic software, communication or meeting tools to highly-advanced Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) solutions. It can be designed or categorised based on the requirement level or reach and can be priced accordingly. The biggest strength of MSMEs is their agility and ease of response to change as per the client’s requirement. If the same is supported by IT and other high technology, they can be a double engine of growth for India.

This can be designed on a PPP model and create employment for service providers too. Post the pandemic, the Government is budgeting huge growth in the MSME sector and planning multiple packages for them. IT is a consistent requirement and always looking for upgradation. Hence if the Government can provide IT infrastructure resources at a nominal fee or free of cost, then it will be a huge saving for MSMEs. On the other hand, due to the bulk purchase of such services, their total outgo will be considerably lower as compared to individual purchase.

If we want to develop the “Made in India” brand as a global signature and beat competition around the world, we have to upgrade all systems of manufacturing and service. This can only be done after improving the IT infrastructure. This one-point cost will save and support millions who are looking to grow and make India a manufacturing and services hub.

(The writer is Associate Professor, Atal Bihari Vajpayee School of Management and Entrepreneurship, JNU)

A step in the right direction

by Uttam Gupta / 13 October 2020It is good that the RBI has kept the repo and reverse repo rates unchanged or else in the current economic scenario any further cut would have been infructuous

In the last bi-monthly Monetary Policy Committee’s (MPC) review announced by its Governor Shaktikanta Das on August 6, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) had kept the policy repo rate unchanged at four per cent. It had also kept the reverse repo rate or the interest rate the banks get on their surplus funds parked with the RBI unchanged at 3.35 per cent. It continued with the “accommodative” stance of the monetary policy as long as necessary to revive growth and mitigate the impact of Covid-19, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target.

In the build-up to the next bi-monthly review (originally scheduled for October 1, which was postponed to October 9, due to the delay in appointment of three external members of the MPC), there was an expectation that there wouldn’t be any changes this time round. Things have happened on expected lines even as the RBI has maintained status quo on key policy rates.

There are four major reasons as to why any further action in gliding the policy rate on the downward trajectory — as demanded by a certain section of the industry — was totally unnecessary.

First, ever since the incumbent Governor took charge (December 2018), the RBI has handed out a cumulative reduction in repo rate of 2.5 per cent. Of this, during 2019, a total cut of 1.35 per cent was delivered in five instalments, the last one being under the policy review announced on October 4, 2019. This brought down the rate from 6.5 per cent in the beginning of the year to 5.15 per cent on its close. The apex bank also tried to boost the economy by pumping liquidity using policy instruments such as Open Market Operations (OMOs).

The above policy moves were made in the backdrop of the slide in the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth that had commenced in the third quarter of the financial year (FY) 2018-19 and continued all through FY 2019-20, the intent being to not just contain the slide but also to revive it. Yet, the deceleration continued with growth plunging to a little over three per cent during the last quarter of FY 2019-20 and the yearly figure settling at a low of 4.2 per cent. But that did not deter Das from continuing with a cut in the policy rate.

On March 27, he reduced the policy rate by 0.75 per cent. This was followed by a further cut of 0.4 per cent on May 22, thus delivering a total reduction of 1.15 per cent post-pandemic. Das also announced on March 27 and April 17 measures like reduction in the cash reserve ratio (CRR), auction of Targeted Long-Term Repo Operations (TLTRO), hike in accommodation under the Marginal Standing Facility (MSF) and so on, to inject total liquidity close to Rs 5,00,000 crore.

Despite these measures, growth during the first quarter of the current FY plunged to minus 24 per cent. During the second quarter ending September 30, though the situation was not as bad, the growth was still lower than during the corresponding quarter of 2019 (for the whole of the current year, Das has projected a decline of 9.5 per cent — that, too, is predicated on positive growth during the last quarter). These trends clearly show that neither reduction in policy rate, nor pumping liquidity in the system are working.

Second, according to Das, of the 1.35 per cent reduction in the policy rate during the pre-Covid phase, only about 0.6 per cent was transmitted by banks by way of corresponding reduction in the lending rate. If transmission is not even 50 per cent then, why keep harping on a cut in the policy rate. Are we to infer that banks are pocketing the differential? The truth is, we are trying to see a strong correlation which either does not exist or is very feeble, if at all there is one. A bank fixes the interest rate it charges from borrowers based on the interest rate it pays on deposits, plus cost of its intermediation. It has also to factor in the cost of non-performing assets (NPAs) or loans which can’t be recovered. Even as the policy rate is posited as an external benchmark for determining lending rate, the latter can’t exactly follow the movement in the former. A perfect correlation would have been possible if only the RBI was its sole source of funding; but that is theoretical, to say the least. Third, despite the RBI opening several taps and banks flushed with funds for onward lending (this was done during FY 2019-20 and on a much larger scale during the current year), the latter have not stepped up lending. During 2019-20, bank credit grew by 6.1 per cent, less than half of the 13.4 per cent growth registered during 2018-19. The trend has got aggravated during the current year. Overall non-food credit off-take from the banking system declined by Rs 1,40,000 crore to over Rs 90 lakh crore during April-July, 2020.

On April 17, while announcing reduction in the reverse repo rate from the existing four per cent to 3.75 per cent, Das had argued it would goad banks to lend to businesses instead of parking excess funds with itself (they were then holding a gargantuan Rs 6,90,000 crore with the RBI). The rate has since been further lowered to 3.35 per cent to ensure that banks don’t keep the money with the apex bank; instead lend. Yet, the excess funds parked by them have crossed Rs 8,00,000 crore. Apart from the disruption caused by the contagion and the resultant compression in demand for credit, sanctions and disbursements have also been impacted by the banks’ increasing risk-aversion and conservative approach to lending.

Fourth, the initial uninterrupted spell of lockdown for three months and even thereafter, intermittent lockdowns at the State/local level, have exterminated demand on a scale never seen before. Apart from lakhs of businesses downing shutters, millions losing jobs or facing cut in wages and salaries, even those who survived the Covid onslaught and had surpluses, could not spend (due to the sheer compulsion of “social distancing”, forcing prolonged closure of a vast swathe of businesses especially in the service sector, like restaurants, cinema halls, multiplexes, tourist destinations and so on).

The gravity of incapacitation engineered by the pandemic can be gauged from the fact that currently, cash with the public is at a historic high of about Rs 26,00,000 crore or 15 per cent of the GDP (assuming 10 per cent contraction in nominal terms during FY 2020-21) — up from the Rs 17,00,000 crore it was at the time of demonetisation in November, 2016.

A major factor that has a profound impact on demand has a lot to do with scams galore. These involve siphoning off funds from banks, non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) or even directly from the public (say by builders) and so on. Running into hundreds of thousands of crores, these add to the personal wealth of a select few, which is either stashed abroad or kept within India as “undisclosed income” (black money). Had this money remained with millions to whom it actually belongs, this would have added hugely to the purchasing power, reduced the NPAs of Banks/NBFCs and increased their ability to lend more.

Unlike the pall of gloom surrounding the August meeting of the MPC, this time the RBI exudes confidence even as the Governor sees the “Indian economy entering into a decisive phase, seeing easing of contraction in various sectors. Deep contractions of Q1 are behind us and silver linings are visible in easing caseloads across India.” He also sees retail inflation to be moderating from the third quarter onward, driven by a bright agriculture outlook and oil prices remaining range-bound. The Governor has also promised measures as necessary “to assure market participants of access to liquidity and easy finance conditions” (Rs 20,000 crore-OMO auction next week and On-tap TLTROs of Rs 1,00,000 crore to be made available till March 2021 — linked to the repo rate — are some of the steps in this direction).

These are add-ons to the existing pool of measures in the same category. Just as those measures failed to deliver, it is unlikely that these incrementals will do any better. It is good that the RBI has kept the key policy rates like repo and reverse repo rates unchanged or else in the current scenario, when the economy is besieged with structural constraints, any further cut thereof would have been rendered infructuous. A holistic approach is needed to address the structural constraints of the economy. This should encompass policy reforms to lift business sentiment and boost investment; tackle NPAs on a war footing; goad banks into proactively taking up project lending; and result in stern measures to deal with scams with greater emphasis on prevention. Sans these, any stimulus won’t be of much use in lifting the economy.

(The writer is a New Delhi-based policy analyst)

Understand psychology for better decision-making

by Hima Bindu Kota / 12 October 2020This approach can help in reducing stock market movements and losses on the bourses

Ever wondered why stock markets have huge upswings or downswings? Most of the times, they are like a domino effect, a chain reaction, caused by herd behaviour. Herding is an inclination of investors to follow the crowd, thus destabilising stock prices. It is a very powerful bias, and in the process of mimicking each other, the impact on the stock prices gets intensified, leading to bubbles when the demand is high and crashes when investors detect overpricing.

This is contrary to the classical finance theory, which believes that investment decisions are taken by rational investors. But are investors really rational? A Boston-based research group reported in 2007 that an average stockholder earned 4.3 per cent per annum returns where the returns of American S&P 500 Index averaged at 11.8 per cent per annum. The reason for this variance was the irrationality of investors of buying high and selling low.

A peek into the past can show that players in the stock market have been irrational since the time the bourses have existed. One of the earliest instances of unreasonable herd behaviour is the Dutch tulip bubble of the 1630s, also known as “Tulip Mania.” When the tulip was introduced as a new variety of flower in the Netherlands, the Dutch people, because of some strange reason, became excited about this new exotic flower and vied to invest in tulip bulbs.

Progressively, the investments grew huge and at the pinnacle of this mania, a single bulb was sold at a price that was more than ten times the annual income of a skilled worker. But when people realised that investments in tulip bulbs were way more than their actual worth, they panicked and started selling tulip stocks, leading to a sharp fall in the stocks, resulting in huge losses.

This and many other subsequent events after this, like the dot.com bubble and the more recent real estate bubble, have led to the belief that investors do not behave rationally and that their decisions are mostly driven by emotions like panic, fear and greed. These instances are in contradiction of the traditional financial theories that are based on efficient market hypothesis, that assume that all the information is reflected in the stock prices efficiently and in a timely manner. So much so that the investors are unable to make any abnormal profits by buying stocks. There are four pillars of traditional finance: Rational investors; efficient markets; traditional portfolio designs; and linear expected returns-risk relationship.

However, stock markets in reality are largely inefficient, which is evident due to various market anomalies, speculative bubbles and over or muted reaction to any new information about stocks. These prevalent conditions in the stock markets suggest that investors are more emotional than rational about their investment decisions, leading to creation of bubbles.

A bubble is created when the stock price is driven higher than its fair value as people invest in these stocks, neglecting the fundamental valuation. Such investments strengthen the overpricing even more and put pressure on the stock prices to generate higher returns for investors, failing which, the selling starts and picks up momentum when investors follow one another, leading to the bursting of the bubble. Behavioural finance, as a discipline, emerged as an attempt to explain the psychology of financial decision-making and how the human angle affects the same. Several researchers believe that principles and morals of people influence their economic, social and financial decision-making. Sentiments like pride, shame, insecurity and egoism also play an important role in investment decisions. By accepting the fact that investors are irrational and have biased decision-making, behavioural finance entends the limitations of traditional finance theories into possible inefficiencies in the financial markets and provides a realistic view.

Research has identified two types of behavioural biases. The first one, a heuristic-driven bias, also known as cognitive bias, acknowledges that investors are investigative in nature and use rules of thumb to process data for decision-making. For example, people predict future performance of stock market movements through historical data. Emotions like overconfidence, anchoring and adjustment, reinforcement learning, excessive optimism and pessimism form a part of this bias. The second one, frame-dependent bias, is where the investors’ decision-making process is affected by the way they frame their options, like narrow framing, mental accounting and the disposition effect.

It can be concluded that awareness about behavioural biases is indispensable since it is unequivocally associated with human beings and its implications are far and wide. Ignoring such behaviour of the decision-making process can prove to be quite expensive in the financial markets as it can result in stock market anomalies. Financial investment managers and advisors can identify investment mistakes if they have a good understanding of this behaviour of retail investors and become more effective by understanding their clients’ psychology and needs. It helps them in creating a behaviorally-adjusted portfolio, which best suits their clients’ requirements. Investment bankers can put this knowledge to use by correctly timing the IPOs and understanding the general sentiment in the stock markets. Behavioural finance also helps financial analysts in forecasting future stock market movements and recommending appropriate stocks for investments. Finally, individual retail investors can use this expertise to make wise, rational and effective financial decisions.

Investors, financial advisors and fund managers are all humans and are subject to biases. Understanding the psychology of financial decision- making can help in reducing the stock market movements and reducing losses on the bourses.

(The writer is Associate Professor, Amity University, Noida)

The dues conundrum

by Subhash Chandra Pandey / 10 October 2020Small business enterprises are given purchase preference quota in procurement by Government and Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs), a pooled quota in bank credit and interest subvention under some Government schemes. The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) were categorised, separately from the manufacturing and services sector, based on investment in plant, machinery and equipment under the MSME Development Act 2006 (MSMED Act). Many MSMEs do not increase their investment for fear of losing their tag and associated benefits. To address this concern, the definition of MSMEs was changed from July 1 this year. By bringing an additional criterion of turnover, a business entity is now classified as a micro enterprise if its investment is upto Rs 1 crore and turnover is upto Rs 5 crore. The corresponding figures are Rs 10 crore and Rs 50 crore for small and Rs 50 crore and Rs 250 crore for medium enterprises. Earlier, the classification was only based on investment, with separate investment limits for manufacturing and service sectors. The exports turnover will be excluded from reckoning for the qualifying turnover to encourage MSMEs to export more without losing their status tag and associated benefits.

The 73rd round of the National Sample Survey 2015-16 (NSS) estimated that there were 6.34 crore MSMEs (6.30 crore micro, 3.31 lakh small and 5,000 medium enterprises) employing 11.10 crore people. By January, only 86.11 lakh MSMEs had availed the facility of online, self certification-based, paperless registration on the MSME Ministry’s Udyog, Aadhaar, Memorandum portal. About 60 per cent are in the service sector and 40 per cent in manufacturing. After the revised classification from July 1, many erstwhile large business enterprises have also now become medium and medium have become small enterprises and so on. So 99 per cent business enterprises are MSMEs and 99 per cent MSMEs are micro enterprises. What is the significance and implication of this change? MSMEs complain of payment delays resulting in liquidity problems. Section 15-24 of the MSMED Act stipulates a 45-day time limit on payment to Small and Micro Enterprises (SMEs). On delayed payment of dues, the debtor is liable to pay interest at three times the bank rate notified by the RBI, compounded monthly. Under the Atmanirbhar package, in May the Government ordered all departments and PSUs to clear all pending MSME dues within 45 days of acceptance of supplies. In July, departments were asked to pay penal interest of one per cent per month on delayed payments. The dispensation applied to all MSMEs, including medium enterprises that were not entitled to legal remedy under the MSMED Act.

On May 14, the MSME Ministry’s Samadhaan website, an online delayed payment monitoring system for settlement of disputes by affected SMEs, listed pending claims of Rs 40,720 crore. Of this, 11.6 per cent were claims from the Central Government. By September 30, the outstanding amount on the Samadhaan portal had substantially come down to Rs 12,598 crore (37,520 cases) despite an increase in the number of SMEs from July 1 --- State Governments (Rs 2,349 crore/3,546 applications), Central PSUs (Rs 2,172 crore/2,211 applications), State PSUs (Rs 1,573 crore/1,355 applications) and proprietorship firms (Rs 852 crore/6,483 applications). The amount shown on the Samadhaan portal does not seem to reflect the true picture of the MSME working capital distress. The amount is insignificant in comparison to the total contribution of MSMEs in the economy (GDP of about Rs 44.5 lakh crore as contributed by MSMEs in 2016-17).

The MSME Minister had informed in May that outstanding payments to MSMEs totalled about Rs 5 lakh crore. Mere exclusion of medium enterprises from access to the Samadhaan portal can’t explain the big gap in figures. Probably many SMEs are reluctant to escalate their payment delays for fear of reprisals like denial of future orders or fault-finding in supplies. Or because they are merely outsourcing arms set up by large business units, unable to bite the hand that feeds it. Hence, there is no reliable data on actual distress caused by stalled payments. Bill discounting offers a solution to the problem of stalled cash flows to MSMEs. There are Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS) platforms for MSMEs to auction their trade receivables through online bidding. Multiple financiers buy their undisputed invoices at a discount. While the financier can wait for payment clearance, the MSME gets the discounted value of invoices upfront. In 2018, the MSME Ministry had mandated all CPSUs and all corporates with a turnover exceeding Rs 500 crore to be on-board TReDS platforms. However, many corporates are not yet registered on these.

By delaying even the acknowledgement of their liability to pay, they are avoiding giving a handle to MSMEs to drag defaulting buyers before insolvency courts. The recent changes in the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) have limited the scope of small operational vendors to trigger insolvency proceedings and a pause/stop button is in place on fresh defaults since March 25 for six months, extendable to one year. The Atmanirbhar package of May included the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS), a Rs 3 lakh crore window of collateral-free loans to MSMEs. Banks could extend an extra 20 per cent outstanding loan to creditworthy MSMEs having non-NPA accounts with Government guarantee. The four-year tenure loans carry a 12-month moratorium on principal repayment and a cap on interest rates, 9.25 per cent for banks and 14 per cent for Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs). The scope of the ECLGS was later enlarged to include even non-MSME business entities, retailers and individual borrowers, proprietorships, partnerships, registered firms, trusts, limited liability partnerships and interested borrowers under the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana, who are now eligible for ECLGS. By September 29, banks had sanctioned loans of about Rs 1.86 lakh crore to 50 lakh business entities and disbursed Rs 1,32,246 crore to over 27 lakh entities under the ECLGS.

MSME registration is voluntary. Only about 86 lakh MSMEs are registered while there were 633 lakh MSMEs as per a 2015-16 survey estimate. Just like unorganised labour, a majority of the MSMEs are not registered with the Government. Not being on the radar of the Government helps the “informal economy” to dodge Government regulations, some of which are indeed outdated and burdensome. They want Government help but are wary of getting registered with it. Many MSMEs don’t register out of ignorance of benefits or the assessment that the risks of getting entangled with the Government are more than the benefits of registration. Though it enables better support, registration leads to anxiety about formalisation and possible Government overreach. For MSMEs, getting relief from the Government without registering is not possible because the latter is accountable to keep a record of who has been helped and by how much. The MSME sector needs increased formalisation and digitalisation to get more commercial credit through digital lending. Under such a system, the sales and payments are recorded through digital payments and invoicing systems, which give the bankers reliable data on sales/turnover and help in the generation of a better credit history. Loans can be substituted with customised credit cards for better transaction level controls with links to the Goods and Services Tax (GST) system and logistics service providers for control on mortgaged inventories. Digital technology can take care of a lot of ills of the past. Even banks have to look out for high quality borrowers, so digital lending is a win-win for both bankers and borrowers. The Government has offered a rather hassle-free registration facility. May be there is a case for giving automatic MSME registration to ECLGS beneficiaries and GST-registered vendors. Of course, Aadhaar-based verification would be a must because there are reports of splitting of businesses to bring them within the lower tax threshold.

The Government expects businesses to become responsible, take care of public safety, employees, the environment and pay taxes. The Government would be emboldened to deregulate if self-regulation by businesses improves. The pace of deregulation is slow only because misdeeds of some keep the logic of regulation alive. An attempt should be made from both sides to address the mutual concerns on why there is low registration. Maybe there is a case for the Government allowing a limited period of regulatory forbearance and amnesty to erstwhile unregistered MSMEs. Without registering, relief would be slow and difficult to come by.

(The writer is a retired IAAS officer and former Special Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.)

Early days yet

by Opinion Express / 10 October 2020The Monetary Policy Committee of the Reserve Bank of India has decided to keep interest rates steady for the time being but with a more accommodative stance, which one could read as allowing banks to be more liberal with disbursals. The meeting ended and the stock exchanges celebrated by climbing, not massively but still enough to display their approval of the decision. The RBI, however, expected the economy to contract by 9.5 per cent in the 2020-21 fiscal, thanks to the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent lockdown. However, one must ask whether the RBI is being a bit too optimistic, with several financial firms and ratings agencies predicting that India will have a double-digit economic contraction this year, thanks to the near-total loss of economic activity in the first quarter. But could there be a reason behind the RBI’s optimism? Some of RBI’s measures include rationalisation of risk weights to all new housing loans until March 2022, which is expected to ease credit availability for the real estate sector. Across several industries, demand has been picking up even before the start of the festive season. Car companies saw wholesale orders pick up dramatically in September. Sales of computers, mobile phones and other electronic peripherals have also increased dramatically. While some industries have changed forever thanks to the pandemic, things are even improving in sectors like hospitality. Deep Kalra, Chief Executive of online travel agency MakeMyTrip, mentioned in The Pioneer Conversations that hotels and resorts are getting booked out for weekends and people are indulging in “revenge travel.” Sure, things are not back to normal and they may never go back to normal or even recapture the sense of business as usual for at least another two years. However, things are improving and may be the third and fourth quarters of this fiscal year will be stronger than that of the past year and that is why the overall decline for the entire year could be less than expected.

At the end of the day, economic growth is a confidence game and if that is returning in the economy, it is contingent upon the Government and the RBI to ensure that it is sustained. India has not jumped in with a massive demand-side intervention as yet but slight rate cuts in GST or even direct taxes could see India’s top consuming class really start spending more, which might help India emerge even stronger from the pandemic. But we still feel it is too early to have such an optimistic outlook.

(Courtesy: The Pioneer)

CHINA’S GAMBIT PART 2: Free Trade and Globalisation

by Percival Billimoria / 08 October 2020How world turned blind eye to Chinese excess

It is argued that the Chinese economic juggernaut, was already on a roll before China’s membership of the W.T.O. It’s GDP, trade gaps and foreign investment numbers right from the mid-seventies till the end of the last century, amply demonstrates this truism. The bilateral trade deficit of the U.S. with China had already exceeded that with Japan. Mr. Clinton and his Western allies cannot therefore be faulted for thinking that the way to close or narrow the ever-increasing trade gaps was to bring China into the fold, enabling freer access to its large domestic market. Indeed, the protocol commitments which China made were far more stringent than ever before, especially after the Uruguay round of talks, which went beyond trade to include agriculture and intellectual property.

It was believed that China agreed to the protocol commitments only be-cause of the imperative of transitioning to a market economy, so as to increase the living standards of its people. China convinced global leaders that this was the case, and the world turned a blind eye to the excesses of a one-party regime, in the hope that a market economy, would inevitably foster democratic values. What was not apparent, nor deliberated, is the reason why this transition would assuredly take place. As it turns out, China today is neither a market economy nor anywhere near a democracy.

While Indian planners discounted the possibility of harnessing water resources as a source for electricity, owing to the social upheaval which would arise from diverting rivers and submerging large tracts of land, China built a dam visible from space. China’s heavy-handed approach to what the communist party believed to be in its national interest was winked at and even justified as the reason for its rapid development. Astonishing double standards for countries which otherwise were keen on exporting democratic values.

Even now, while calling out its ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy, there are still many in the West who would love to wish away the fact that it has created a new evil empire, far worse than the Soviet Union could ever be. The world is ready to overlook its misplaced belief that free trade would inevitably result in a market economy, which would in turn foster a democracy. There is no explanation for how this transition was hoped to be achieved and if there is one, it is at best fallacious, at worst delusionary.

The view that free trade would somehow persuade China to adopt a more open form of Government failed to recognise that totalitarian communist regimes march to the beat of a different drummer. The ideals and interests of such a regime are very different from that of the West. Moreover, trading or doing business, is not the same thing as being a market economy. State-owned enterprises, or States themselves, do both. A State controlled economy differs from a market economy not in the identity of its constituents, but rather the extent of influence and control exercised by the State. Why does it take a pandemic of dubious origin and an increasingly aggressive foreign policy to realise that Chinese companies are owned and controlled by senior functionaries of the communist party? Or that the People’s Liberation Army owes allegiance to the party and not the country.

In over two decades and some, what started as a labour arbitrage for easy to manufacture components, has culminated into an estimated 30% of the world’s supply chain being dependent on China’s manufacturing sector and the trade deficit of the U.S., as well as the rest of the world, has burgeoned into unmanageable proportions. A large part of this may be attributed to China’s clever tightrope walk of the W.T.O.’s flawed enforcement mechanism, allowing foreign investment in industries on the condition of transfer of technology and building in subsidies to local units. Although, direct subsidies such as tax exemptions have been documented, there are other covert, incentive based methods, such as affording exporters preferential or cheaper access to land or finance. Another commonplace strategy is “dumping”, where quite simply Chinese exports flood the markets with far cheaper products, ruining local manufacturers. This is apredatory practise, which comes with a cost which is then recouped in higher prices.

While these practices which are quite visible, were tolerated due to an inherent vested interest of the Western economies, what many missed is the one singular flaw in the W.T.O. mechanism, which is that there is nothing to prevent currency manipulation. There can be no free trade leave alone a free market, in that case. The problem here was also that many who cried foul did not fully understand the mechanics of foreign exchange markets and how a country manipulates the value of its currency to keep it artificially low relative to the dollar.

The impact of currency manipulation can best be explained by an illustration. Suppose the intrinsic value of 1 kg of wheat equals that of 1 kg of ginseng. One could either barter the goods with the U.S. shipping the wheat to China and taking ginseng in exchange, or else payment would be made, exchanging (say) $1 for Y1. If this was the only trade between the countries, there would be exchange rate parity.

However, if the U.S. consumed more ginseng than China consumed wheat, the increased demand for Yuan (to import the Ginseng) would make it dearer, resulting in the price of Ginseng to also rise. This would continue until the increased price results in the demand for Ginseng to fall, consequently lowering the trade gap in the hypothetical case. This is the reason why no trade gap can increase steadily – trade equilibrium would result, unless of course, either the price of the goods is cheaper (because of hidden subsidies) or the value of the currency falls (because of currency manipulation). China has cleverly used a combination of both. Frequent market interventions and flooding the currency markets and the U.S. reserves with yuan by buying up U.S. bonds, leads to a relatively lower currency value. The inevitable result is a vicious cycle where Americans invest in China, and purchase their goods, while China buys US debt and property.

Whether the American multinationals were complicit in the creation of this monster or not, there has been a collective failure to recognise that this situation is unsustainable. Now that the chickens have come home to roost, one may well ask – what lies ahead?

A taxing question

by Uttam Gupta / 06 October 2020

As pointed out by the nation’s top auditor, there are irregularities galore in the management of the various cesses as they have been appropriated to manage deficits

Reining in the fiscal deficit has always been a challenge for the Centre especially after the enactment of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, 2003, which requires it to maintain the shortfall within a specified threshold. At the same time, there are certain thrust areas, such as education, roads and other infrastructure, telecommunication networks in rural areas, exploration of oil, gas and so on, which the Government feels won’t get the desired funds in the normal course of budgeting. This led to successive dispensations to think of a special tax or cess — a form of tax charged/levied over and above the base tax liability of a taxpayer. These include USO (Universal Service Obligation) levy imposed on telecom service providers, cess on Crude Petroleum Oil (CPO), Road and Infrastructure Cess (RaIC), Primary Education cess (PEC), Secondary and Higher Education cess (SHEC), Education cess on Imported Goods (ECIG), R&D cess and so on. The proceeds from these taxes are credited to the Consolidated Fund of India (CFI) and subsequently transferred to a non-lapsable fund, for instance, the USO Fund (USOF) — based on the appropriation approved by the Parliament — created in the public account for utilising exclusively for the purposes for which it is collected. The financing of the specified activity thus gets shielded from the vulnerabilities associated with the normal budgeting exercise.

Prima facie, the idea sounds appealing. But the big question is if this is working. Are funds being utilised for the declared purpose? Are the outcomes commensurate with the intent? To answer these questions, let us look at the reports of the Comptroller and Auditor-General of India (CAG) brought out from time to time. The Centre charges licence fee at eight per cent of the adjusted gross revenue (AGR) of telecom service providers. This includes five per cent as appropriation for crediting to USOF (set up in 2002) while the balance three per cent is retained with the general exchequer. For 2018-19, the CAG has noted that out of a total collection of about Rs 6,900 crore as USO levy, only Rs 4,800 crore was transferred to the USOF, implying a shortfall of Rs 2,100 crore. Against a collection of Rs 1,10,000 crore since 2002, the amount disbursed till date is only Rs 54,500 crore. The balance Rs 55,500 crore remains with the CFI. Coming to the SHEC, the Government started collecting this levy from 2006-07 and until January 2019, could harness about Rs 94,000 crore. The entire amount has been retained in the CFI. In this case, even the public account christened as Madhyamik and Uchchtar Shiksha Kosh (MUSK) was created only in August 2017 (more than a decade after the collection started) and has not been operationalised so far.

The R&D Cess Act, 1986, provides for levy and collection of cess on all payments made for the import of technology. The proceeds of this were to be disbursed as grants-in-aid to the Technology Development Board (TDB) set up in 1996. During 1996-97 to 2017-18, a total of about Rs 8,000 crore was collected. Of this, a mere Rs 800 crore was transferred to the TDB. Furthermore, though the cess was abolished from April 2017, it continued to be collected during the following two years, viz. 2017-18 and 2018-19. In case of Clean Energy Cess (levied on coal supplies) since 2010-11, the amount denied to the designated fund, viz. National Clean Energy Fund (NCEF), was about Rs 44,500 crore. Likewise, in the case of the RaIC, (earlier nomenclature Road Cess), there was a “short transfer” of about Rs 72,000 crore in the amount collected since 1998-99 till March 31, 2018 to the Central Road Fund (CRF), the public account.

Unlike other taxes, which are part of the “divisible pool” to be shared with the States as per the recommendations of the Finance Commission, the Centre gets to retain all of the cess (which goes to the CFI and is available for general use). Because its finances have come under serious stress during the current pandemic year, its reliance on RaIC has increased by leaps and bounds. It raised central excise duty (CED) on petrol and diesel twice this year in March and May, mostly through hike in the cess. At present, out of CED on petrol of Rs 33 per litre, Rs 18 per litre or 54.5 per cent comes from the cess. For diesel, out of Rs 32 per litre CED, RaIC is Rs 12 per litre or 37.5 per cent. The Government also levies the Oil Industry Development (OID) cess currently at 20 per cent ad-valorem on the price that domestic producers of crude, namely the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) and the Oil India Limited (OIL), get on their supplies from nominated blocks and pre-NELP (new exploration licensing policy) exploratory blocks. Collected under the Oil Industries (Development) Act of 1974, though the cess proceeds are intended to fund research, exploration and development work, yet the money remains with the CFI.

As pointed out by the top auditor, there are irregularities galore in the management of the cesses. These include short or “nil” transfer of cess proceeds from the CFI to the dedicated non-lapsable fund in the public account set up for the specified purpose. In certain cases, the public accounts were not even created long after the Government started collecting the tax. In others, it continued to collect even after the same was abolished. The Government has, in fact, used them primarily for increasing its “general revenue” and meeting the fiscal deficit target. If an overwhelming share of proceeds (or even the whole of it) from the cess remain with the CFI, what else one should conclude? Or the dedicated public account where the money has to go (for use in the intended purpose) is not even created, what else can one infer?

Meanwhile, these cesses continue to inflict damage on the stakeholders who bear their brunt. Look at the impact of the five per cent USO levy on telecom service providers. In an intensely competitive environment, wherein they are compelled to keep the tariff low (this is also in sync with the dire need to make these affordable to consumers, with a majority of them having a low income), such levy has the effect of raising the cost of services and making them unviable. In fact, there is a strong case for scrapping this tariff.

This was recognised by none other than the Union Telecom Minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad, when he wrote to the Finance Ministry: “Given that rural tele-density has significantly increased since the time the fund was set up, it is proposed that the USO levy may be reduced from five per cent to three per cent. The two per cent USO levy reduction may be made available to the telecom service providers provided that this amount is utilised by them for carrying out research and development for development and deployment of indigenous technologies in the country.” Yet the Government continues with status quo, the sole reason being easy availability of funds (from USO levy) which can be used for plugging its general deficit. Look at the RaIC, which accounts for a major slice of the CED on petrol and diesel and together with the cascading effect of Value Added Tax (VAT) leads to a bizarre situation whereby taxes alone account for about two-third of their prices at the pump. The high fuel price contributes to high inflation and higher cost of fertilisers and food. Since the Government controls their prices at a low level to make them affordable, much of the extra revenue is given back as higher subsidy.

To that extent, the revenue gain from the cess (besides other taxes) is imaginary. Likewise, 20 per cent OID cess on domestic supplies of crude (besides the 20 per cent royalty ONGC/OIL need to pay to State Governments in respect of onshore supplies and 10-12.5 per cent royalty to the Centre on offshore supplies) impacts the viability of producers at a time when their realisation from sale has plummeted (courtesy, the steep decline in the international price of crude).

Despite the cesses not serving the intended purpose and their negative consequences, the mandarins in the Finance Ministry appear to be in no mood to say goodbye to them. Amid the current crisis created by the pandemic, when the tax collections have been severely impacted and expenditure commitments have ballooned, they may not even entertain any discussion on this. Nonetheless, there is dire need to put abolition of these cesses on the high table as these are not only counter-productive but also make our policy planners and administrators complacent with regard to sustainable ways of balancing the budget. Will the Government go on a course correction? One can only wait and watch.

(The writer is a New Delhi-based policy analyst)

Lessons from Vodafone

by Subhash C Pandey / 01 October 2020There should be a certainty about tax liability but retrospective changes in tax laws are undesirable. They negate the basis of key investment decisions

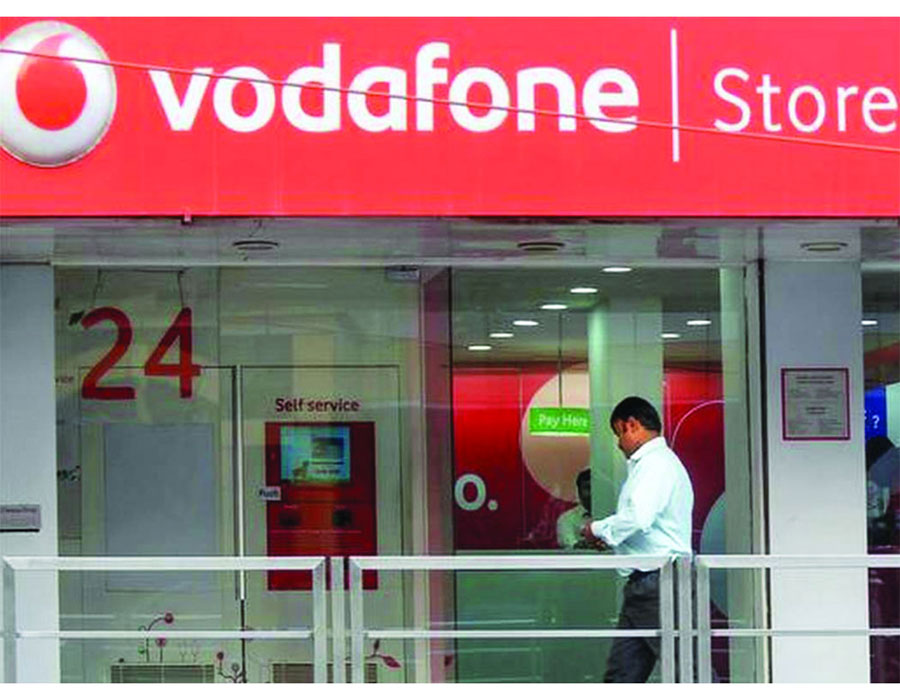

Death and taxes are certain but when, how or why can be most uncertain. Experts find ways and means — sometimes genuine and sometimes sham — of minimising tax liability. This is to contextualise an arbitral panel under the Permanent Court of Arbitration rejecting India’s income tax claim of about Rs 22,100 crore from Vodafone.

The tax dispute goes back to 2007 when Vodafone International Holdings, a company registered in the Netherlands, acquired CGP Investments Limited, a company registered in Cayman Islands. Normally, acquisition of one foreign company by another foreign company should have nothing to do with Indian law and taxmen. A company’s shares are supposed to be situated in the country where it is registered. Legally, only Cayman Islands’ Government had the right to tax the capital gain made by the shareowner as the share sale took place there. However, Cayman Islands does not impose income tax or capital gains tax (and that is why so many companies are registered there.)

Through other offshore entities, the Cayman Island company controlled CK Hutchison Holdings Ltd’s 67 per cent stake in the Indian company, Hutchison Essar Ltd (HEL). So the end result of this share sale was that the ultimate “owner” of the Indian company got changed from the Hong Kong-based Hutchison to the UK-based Vodafone, both controlling the Indian company indirectly through a chain of intermediate companies. Since the share sale in Cayman Islands did not entail any income tax, it was a “tax-efficient” arrangement.

HEL was a joint venture company formed by the Hong Kong-based Hutchison and Essar Group. HEL held a telecom licence. The share sale transaction in Cayman Islands meant that the Hong Kong company Hutchison ceded control of HEL to British company Vodafone to the extent of 67 per cent of HEL shareholding. Had the shares of the Indian company been sold directly, Indian income tax would have been unquestionably payable on capital gains. But Vodafone indirectly acquired 67 per cent control in HEL from Hutchinson in a $11.2b deal.

Indian taxmen did not like what they saw as a tax-dodging arrangement. They argued that the Cayman Islands’ share sale was actually an indirect sale of shares of the Indian company. They raised a demand (2009) of $2.2 billion as capital gains tax. With interest and penalty, the total tax demand rose to Rs 22,100 crore. Vodafone contended that it was not liable to pay tax because the transaction did not involve transfer of any capital asset situated in India.

On January 20, 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that the Government had no jurisdiction to levy tax on overseas transactions between two foreign companies. A sale transaction between two foreigners was beyond Indian tax jurisdiction even if the subject matter of sale was controlling interest in an Indian company having valuable assets. No Indian company had directly sold anything.

The Government requested the Supreme Court to lift the corporate veil to see the true substance of the transaction, the true end-beneficiaries of the transaction and not go by mere form, or the corporate boundaries of shell companies through which ultimate owners operate. These arguments were not accepted. The top court said that the law as it then stood did not allow lifting the corporate veil based on such interpretations. Instead of “look through,” the court adopted a “look at” approach.

Unwilling to give up the tax claim, the Government amended the tax law retrospectively with effect from June 1, 1976, giving itself the power to re-open past mergers and acquisitions if the underlying asset was in India. Vodafone then contested the claim under the Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) between India and the Netherlands and between India and UK.

A PCA arbitral tribunal recently adjudicated the investment treaty arbitration dispute and rejected the Indian tax demand. The retrospective change in income tax Law in 2012 was held to vitiate the guarantee of Fair and Equitable Treatment (FET) given to Dutch/British investors under the BITs.

The Government can now appeal against the order in the High Court of Singapore. If not, it has to spend about Rs 85 crore (Rs 40 crore to PCA as 60 per cent of litigation cost and Rs 45 crore refund to Vodafone).

Another similar arbitration involving UK’s Cairn Energy Plc is expected to be concluded soon, where $1 billion of Cairn Energy’s shares have been confiscated.

India and similarly placed financial resource-starved countries face this dilemma. We want to welcome foreign capital to bring financial resources and technology to expand the earning capacity of the Indian economy, create jobs and raise income levels. The investors have a legitimate expectation of a fair and equitable non-discriminatory taxation and regulatory regime, ease of doing business but the Government also has a legitimate interest in collecting taxes. Last year, we reduced corporation tax for new manufacturing companies to a record low of 15 per cent.

There should certainly be a certainty about tax liability but retrospective changes in tax laws are undesirable. They change assessment of future profits and may negate the very basis of important investment decisions.

Discerning eyes can see that the primary driver of the Cayman Islands sale was acquiring controlling interest in the Indian telecom company and the deal was structured to make it an offshore transaction beyond the reach of Indian taxmen, an innovative tax avoidance measure. The world’s rich shift their incomes and wealth from their high-tax home countries to these “tax haven” countries like Cayman Islands having almost no income tax. How can “tax haven” countries defend giving shelter to people running away from their taxing home jurisdictions is a big international debate. It is an ideological battle between tax-free Governments of these countries and remaining “tax-and-spend” Governments who want to impose their ideology on nations following “minimalist Government” ideology.

One country’s “black money” (tax-evaded income) is a source of survival for another. That is how “tax havens” flourish. One would wish greater international cooperation in enforcement and “tax-and-share” being put in place but the interminable debate on limits of taxation, sovereignty and protection to criminals, acceptability of national laws on crime and taxation by outsiders, unfair/unjust/excessive taxation and fair end-use of tax proceeds block any such agreements from fructifying.

Taxation of foreigners and foreign companies presents special challenges. There is a clash between two principles. One is the US system based on “situs” of the assessee’s nationality and the other is the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) system based on “source” of the assessee’s income.

The tax liability attaches to assessees based on their nationality. A Government may tax its citizens and the companies registered under its national laws. The 2012 Supreme Court judgment was based on the law then in force which limited extra-territorial application of tax laws.

The “situs” of the taxed entity is now pitted against the “source” of the entity’s income. The OECD project on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) is gaining traction.

More and more Governments are now coming to clash with the classical worldview on foreign taxation and asserting that a Government’s jurisdiction extends to foreigners and foreign companies who may be present on their soil or drawing sustenance from it. Big MNCs like Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Netflix are inviting global attention for earning from different countries without contributing enough to the local public exchequer.

There is a global consensus regarding the need for a comprehensive mechanism to tax cross-border transactions in the digital economy. OECD, UN and EU are working on a resolution. We amended the Income Tax Act in 2018 to bring the concept of ‘Significant Economic Presence’ from April 1, 2019, and introduced equalisation levy (Google tax) in an attempt to tax incomes being collected by foreigners from Indian consumers. In an imbalanced world, the terms of trade and investments are not always favourable to emerging economies. They also don’t have the freedom to print money and spend. Balance has to be struck between fair taxation and honest tax compliance in form and substance.

(The author is an IAAS officer, superannuated as Special Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.)

Amnesty shuts shop

by Opinion Express / 30 September 2020The human rights watchdog may have looked at India through a Western prism but can we dispute its findings on Delhi riots?

The trouble with human rights watchdogs is that they have, by virtue of countering the establishment narrative, assigned themselves a certain kind of legitimacy and credibility without realising that some of their own investigations are compromised by subjective assessment rather than objective investigation. This has also been a problem with Amnesty International, which has many times been accused of looking at India through a Western prism. But as a robust democracy, we have it within ourselves to accept vilification and acknowledge cogent counterpoints. We shouldn’t need lobbyists to get the other side of the story; our media should be free to do that. Besides, by and large, the organisation has an international acceptability even if we take some of its reports with a pinch of salt. But by targetting Amnesty, which says it is now forced to shut shop in India because the Government has completely frozen its bank accounts here, we appear to be in the bracket of oppressor and authoritative regimes like China. And considering its activists have been particularly penalised for tracking dissent pan-India over the last two years, it gives them a moral upper hand and claim a witch-hunt. The reasons that the organisation lists behind the Government crackdown on it are the same as those cited by tormented civil society activists — namely “unequivocal calls for transparency in the Government, more recently for accountability of the Delhi police and the Government of India regarding the grave human rights violations in Delhi riots and Jammu & Kashmir.” Frankly, even without the Amnesty’s reports, there is far too much on-ground evidence of the charges it has made. And the way the disclosure statements and names in the chargesheet of the Delhi Police on the city riots have been circled out, targetting the liberal intelligentsia, protesters and activists while leaving out the inflammatory fringe Rightists, there is a move to freeze the right of democratic dissent. So the timing of its India exit suits Amnesty more than us at this point of time.

It would have made more sense had the Government zeroed in on Amnesty in 2016, when it was booked in a sedition case for allowing “anti-India” slogans on Kashmir at an event in Bengaluru. But to pursue it for violating foreign funding rules in 2019 obviously raises questions on intent. Amnesty though claims that its India operations have been funded domestically. The immediate context seems to be the report it released last month on the complicity of Delhi police in the riots. Yes we must defend our pluralism and challenge the official narrative. But by hounding out Amnesty, we have a public relations battle ahead. Nothing will happen to it. Nothing would have if it had been allowed to continue.

FREE Download

OPINION EXPRESS MAGAZINE

Offer of the Month