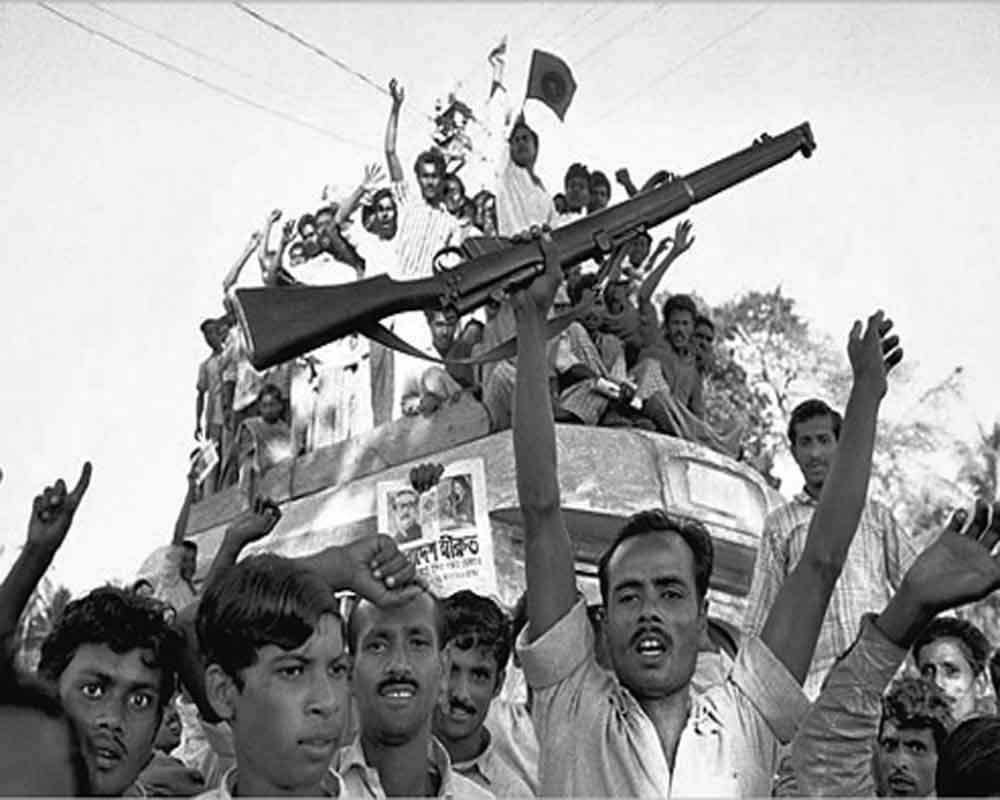

Recalling an unforgettable view of history’s moving procession that resulted in the crumbling of the old order and gave birth to a new nation

If I remember rightly, it was Thursday, March 25, 1971, and my MA (History) final exam was round the corner. We in India then had the audible, omnipresent, omniscient and ubiquitous All India Radio but no electronic visuals. Hence, hearing the evening radio news and reading the morning newspaper were my childhood addictions, exam or no exam. My father — an extraordinary scholar of income tax law, English, Bengali and Sanskrit languages, Astrology (including charting a horoscope) and Economics, and a celebrity senior civil servant of the federal Government of India, who was originally born in and hailed from 2 Toynbee Circular Road, Tikatuli, Dhaka, (then East Pakistan) — was not the type to disturb his son for radio news during exam season. That day I, too, seemed to have something else in mind for emperor Ashoka and Buddhism as a possible question for my paper.

Nevertheless, there suddenly came a stentorian voice from our C-II 17 Wellesley Road, New Delhi — 110003 ‘radio room’. “Come immediately” was the two-word command. Usually serene, serious yet ever-smiling, my father suddenly lit upon hearing the All India Radio news that the charismatic Bengali leader, widely respected and revered as Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, had given a clarion call to the people of (then) East Pakistan, firing the first salvo at the West Pakistani Punjabi-speaking military junta from Dhaka’s Ramna Maidan: “Aamago share shaat koti zanagan re tomra dabayya raakhte parbaanaa (You oppressive rulers, you will never be able to suppress we seven-and-a-half crore Bengali people).” We instantly felt the electrifying effect and potential tremor, almost after 24 years of Partition days, in the ‘radio room’ of the Hindu Bengali refugee in Lutyen’s zone of New Delhi.

Thereafter, things moved at a high speed. Owing to his professionalism, probity and spotless past, my father was one of the two Bengali-speaking senior civil servants, whose residence was identified by the Government of India as an ‘informal meeting point’, should the need have arisen. My MA exam ended on Saturday, May 15, 1971, and results were out on Monday, July 05, 1971. I was happy with my result but was happier owing to the fast unfolding scenario of a possible emancipation of an enlightened and inherently simple Bengali-speaking people with whom we were so close in heart, mind and thought and shared history, geography, culture, language and tradition.

Soon, however, came Wednesday, August 18, 1971, the appointed date for an ‘informal meeting’, closely coordinated by Shri Ashok Ray, the then Joint Secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs, and other organisations of the State. Commencing at 5.30 pm and ending at around midnight, it was a party; a reunion of sorts, high on feeling and emotion, love, tears of joy, passion, fraternity and feasting. It was a gathering of 150 people of whom at least 80 were from the land of Bangabandhu, including Janab Tajudin Ahmed. Half of them had escaped, God only knew how. At least two families had driven down in their ‘Made in Japan’ Nissan and Toyota cars, which were a rare commodity in India of 1971.

The outcome of the meeting was essentially a commitment to do everything necessary. The Government and the people of India were one with the Bengalis under Bangabandhu. All present in the meeting had the same goal, in different ways, irrespective of their nationality and ethnicity. I vividly recall one spontaneous and repeated slogan, ‘Joy Bangla’, reverberating through the hot, humid night of that August day in 1971.

Two more meetings subsequently took place in two different places in Delhi, which I could not attend owing to my preparation for competitive exams. As things were heating up, I travelled to spend the winter with my maternal aunts in Asansol and Calcutta (as it was known then). My stay in Asansol lasted for five days as war broke out on Friday, December 3, 1971. I took a train the next day, December 4, 1971, for Calcutta. The three-hour journey was an experience by itself as the train moved with all lights off in the chair car. Howrah station was pitch dark but packed with passengers, police and Railway personnel. Home guards were extra vigilant, navigating all and sundry and the half-an-hour road to Alipore residence of my aunt took two hours like a Delhi-Calcutta flight as I reached at 11 pm.

The following day dawned with my frantic attempt to catch up with Major General Bishwa Nath Sirkar (whom I had known before) in Fort William, Headquarters of the Eastern Army Command. Maj General Sirkar, a Second World War veteran, who saw action on several fronts, was an armoured corps officer par excellence (belonging to Central India Horse). Being a strict disciplinarian, with frugal habits and exemplary probity, he never sought publicity and was never flashy. The Major General was handpicked overnight (rather plucked) by Army Chief Sam Manekshaw and transferred from the post of Military Secretary to a newly-created post in the Eastern Command Calcutta, exclusively for cooperation with the Mukti Bahini.

Consequently, whereas the world today knows who did what in 1971, hardly anyone can either remember or recall his invaluable contribution to/in the liberation movement of Bengalis in the East and the role he played in the actual combat of the 14-day war. After the 1971 war, Sirkar became Lieutenant General but resigned after a serious difference of opinion with the then Defence Minister of India. He had several years of service left at the time of his premature departure.

I remain eternally grateful to that great soldier and noble soul for helping me to “see the front” for two days after Sunday, December 12, 1971, when the writings were already on the wall. After a resounding firing to deter me from “seeing is believing”, the gentleman in the General relented and “put me on” to Corps II, operating from Krishnanagar.

The rest, as they say, is history. At the age of 23, I had a remarkable, unforgettable side view of the moving procession of history, resulting in the crumbling of the old (dis)order and the birth of a new nation, not in the distant horizon but in our vicinity. Between 1947 and 1971 came alive two nations: The first under bondage; the second as an un-caged bird with the unrestricted horizon of thought and action as its domain.

(The writer is a former college lecturer and civil servant. Now a researcher, columnist, alumnus of National Defence College of India, advocate, Delhi High Court and Supreme Court and author)

Writer: Abhijit Bhattacharyya

Courtesy: The Pioneer

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)