Surely, India can redeem itself from the calculated chaos of persecution, pogrom and detention camps by moving towards civic and constitutional morality

Visuals of marauding mobs, grief and absence of law enforcing agencies bring back to many the painful memories of the Partition. There is a constant switching of places between the perpetrator and the victim, as depicted by Urvashi Butalia in her classic The Other Side of Silence. There is no perfect victim and the role of victims as perpetrators and perpetrators as victims keeps the hate narrative going. The real question is, can any amount of revenge achieve ends of justice or give closure? Or, is it that vigilante justice only succeeds in creating another agonising sense of victimhood?

The vigilante mode of “punishing” soft targets or labelling them as “perpetrators” turns them into an “object” of hate, caught in the eye of a storm. These soft targets, allegedly guilty of past perpetration, fall victim to violent retributions. They are also dubbed as “undesirable” and even “illegals.” Being a soft target, they are profiled as belonging to a different and less than equal human group or identity.

The recent attack on a Bengali worker in Thiruvananthapuram on not being able to produce an Aadhaar card, or the alleged detention of Bengali migrant workers in Pune by vigilantes, are classic examples of painting someone as an “illegal” without bothering to verify the truth.

The use of religious flags to differentiate a Hindu house from a Muslim home in times of communal tension is a frightening demarcation of the targetted other. The recent anti-immigrant public discourse across India thrives through this plot of segregation and violence in the name of punishing the perpetrator. The widely-shared viral image of a persecutor and the victim furthers the process of othering and segregation.

In the domain of everyday transactions, asking for proof of identity has become the new normal. Be it under a surveillance camera, face identification or simply through an identity check, an intentional segregation of the “other” as suspect is carried out in the name of finding an “illegal Bangladeshi.” This lays bare the everyday operation of a surveillance society that would act as the forerunner of a “surveillance State”, which is not sanctioned by a constitutional Republic like ours.

Two issues arise here: Does a surveillance society subjectively transform a democratic, constitutional apparatus into a surveillance State? Alternatively, does it just confine itself at the level of the public? Overt determination of identity by proof or by tracking and profiling does not keep the State at the back anymore. Although the State cannot control the visual effect of on-camera scenes of aggression and lynching, to which it can respond only later. In the meantime, violence endows perpetrators with a sense of triumph. While instigators, who triggered the violence appear on the scene only later, with support of their sponsors in power. This makes law enforcers toothless and they become mute spectators of orchestrated violence. A surveillance society helps the henchmen spread a doctored narrative of violence. This is how the victim’s identity is often blurred or altered by terming him/her as violators or guilty. Similarly, one who is identified as the perpetrator could also be swapped from one side to the other. This new art of shifting blame in the form of present or past guilt, creates an image of the “other” who is tasked to prove his identity. In this way, the present practice of legal adjudication in Assam’s Foreigners’ Tribunal places the burden of proof on the “accused.” Until a person proves herself/himself to be an Indian citizen, s/he remains a person of uncertain nationality.

It is a similar situation where migrant labourers, minorities and generally those who are considered as outsiders, is concerned. A surveillance society creates its own outsiders from the figure of a migrant.

The anti-immigrant rhetoric furthers this strange imaging of the migrant who travels to a new place. The migrant is couched in the image of the persecutor or the perpetrator against the native, by citing a narrative such as the Partition. In the safe spaces marked for a particular group or identity, the migrant becomes an illegitimate intruder.

However, this logic of othering can even make the insider a victim. Alleged cases of Bengalis termed as Bangladeshis in Bengal by security forces in public spaces like metro stations and railway platforms point to this nature of harassment of an insider. The ban on fish-eating in various schools in Kolkata run by certain community- based organisations and not allowing fish eaters in some housing complexes in the city point to such racially-discriminatory practices on an insider.

The insider victim or the outsider are all subjected to suspicion and discrimination on the basis of cultural differences that can assume a form of racism even.

The culture of law is such that it goes by what is called “reasonable suspicion.” Entries pertaining to the National Population Register (NPR) ask for the father’s birthplace and NPR rules allow officials concerned to segregate doubtful cases. This is a complex interplay of suspicion and surveillance for the identification of the “illegal”, using NPR data. Such proof seeking and surveillance create conditions of discrimination and exclusion of the cultural and religious other.

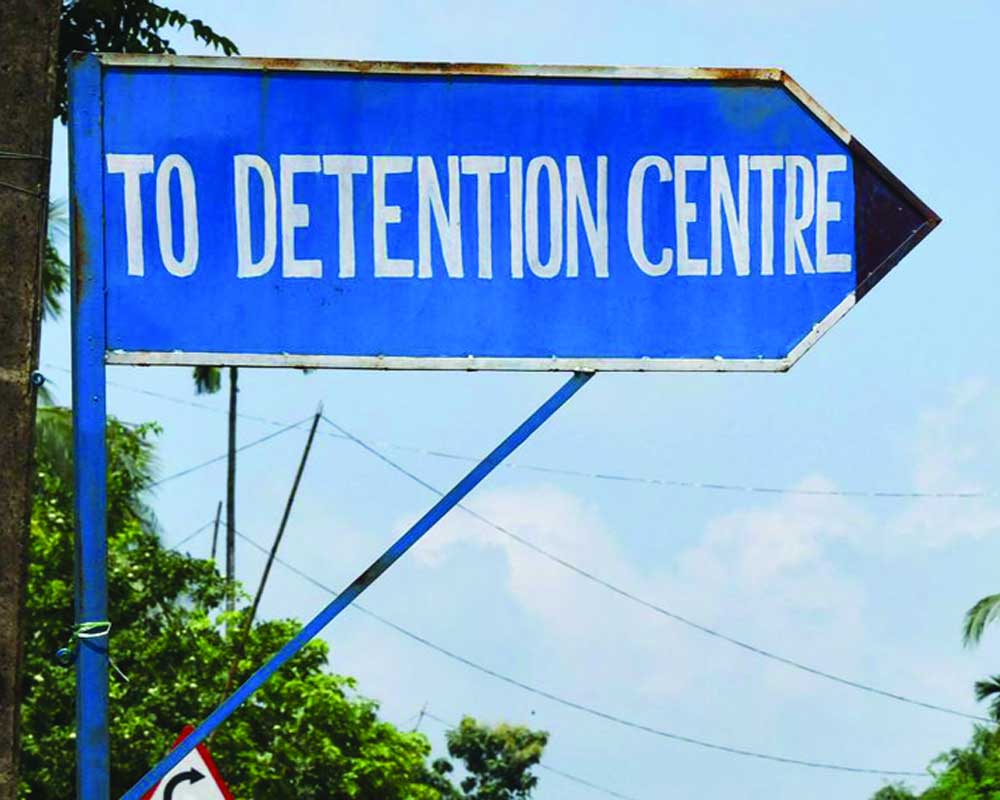

Punning on author Timothy Huge Barrett, one may say that the “reason” of suspicion is clouded by the reason of unreason. Suspicion never fails to find a reason, whether it stands the test of truth or not. People declared as foreigners by Assam’s Foreigners’ Tribunals and lodged in detention camps were later found to be genuine Indian citizens. To know why suspicion and its reasons are unreasonable in going after a perceived “illegal”, one can only look at the religion, language or origin of the so-called “illegal.”

In most cases, it would be someone who does not belong to one’s own community. Such a preconceived idea of “we” and “them” never draws a line of distinction between vigilante legalism and constitutionalism. On and off- camera violence on “them” further constructs the identity of the victim in devious ways to cloak reasons of/for vigilantism. Contrastingly, cases of many victims of miscarriage of justice, as it happened in Assam’s NRC exercise, point to limits of processes of legal adjudication of citizenship.

The new norm of surveilling, snooping and othering a stranger changes the welcoming attitude towards the “other.” The drive to find “illegals” among strangers becomes an obsession. This obsession with “illegal immigrants” creates blind spots in our everyday relationships with the other. The “illegal immigrant” is mirrored in many ways, such as doubtful voters and foreigners, who legitimise racist attitudes towards others.

Is India fast moving towards such legal blinds that allow for a legal architecture of discreet probe into citizenship of its own people?

Suspicion leads to illegal checks, physical and mental harassment of the “other” on ethnic, racial, religious and linguistic lines. It can even pass as “reasonable suspicion.” The result is that a non-immigrant, non-border-crosser Indian migrant citizen could be suspected to be an illegal Bangladeshi or a Nepali, or a Chinese, depending on how one looks.

Legal resonance for this vestige of suspicion is found contextually. The Gauhati High Court declared that voter’s ID, PAN, passport, land revenue receipt and so on do not prove citizenship conclusively in a specific case. More generally, Article 326 of the Constitution makes citizenship a precondition for being a voter and hence a voter cannot but be a citizen. Specifically, the recommendations made by Supreme Court in the Lal Babu Hossein versus Electoral Registration Officer case in 1995 make it clear that there must be sufficient material evidence before someone is suspected to be “illegal”, which in most referred cases of suspects is rather shoddily observed. Hence a large number of Indian citizens face the danger of “suspicion” turning them into an “illegal” and a subject of hatred.

Surely, India can redeem itself from such calculated chaos of persecution, pogrom and detention camps by moving towards civic and constitutional morality.

(Writer: Prasenjit Biswas ; Courtesy: The Pioneer)

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)