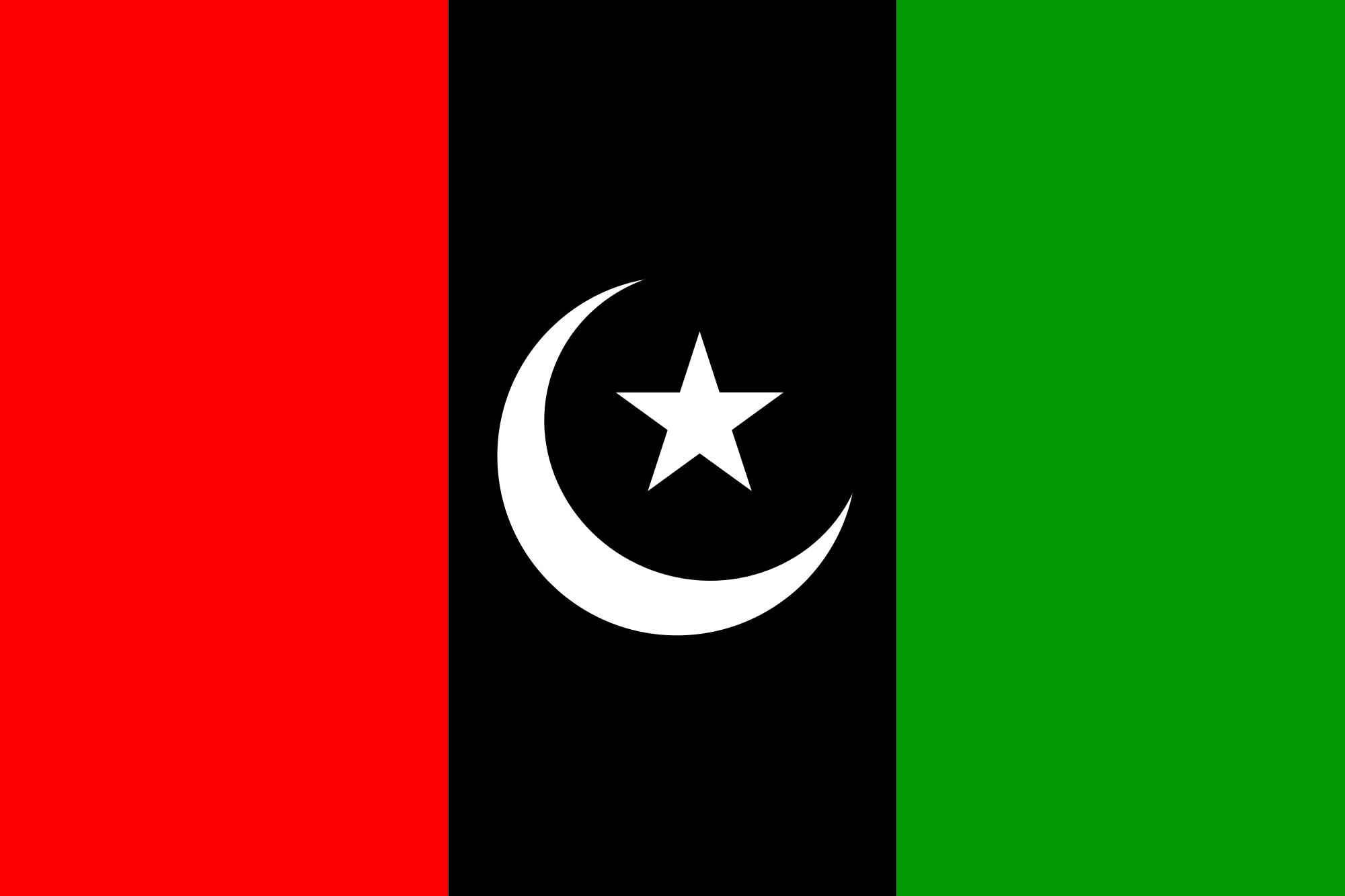

The PTI, similar to PPP and MQM, used a conceivable image to, personally, reinforce their leader.

In 1991, I worked as a young reporter at an English weekly in Karachi. In those days, newspapers and magazines of the city would often receive photographs of former Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) chief that were to be published without any questions. The MQM had risen to power in Karachi in 1988, and by 1990, it had reached a peak in its electoral strength and political influence. I remember, the party would frequently send photographs. Most of them showed Altaf Hussain delivering fiery speeches at rallies, but there were others as well, such as one showing him cutting a huge cake with a sword in Hyderabad! For most editors in Karachi, not publishing the photographs was not an option. In late 1991, the weekly magazine I was a part of received a photograph of a flower. Inside the flower was what seemed to be Altaf’s image. My editor had no clue what to do with this photo. The photo had come with a note written by a local MQM leader, which claimed that Altaf’s image had been discovered inside a flower at a park in Karachi. The editor decided not to run the photo. But next day the photo appeared in a few Urdu newspapers. The editor received a phone call from a senior MQM leader. He knew that the weekly had decided not to use the picture in its next issue. He did not ask why. Instead, he told the editor that he expects to see the photo in the next week’s edition. He must have said this in an intimidating manner because the bizarre photo eventually appeared in the magazine.

Why would a powerful political party need to reinforce its leader’s image through a fantastical claim? Perhaps the party wanted its followers to believe that the leader’s greatness transcended mortal political qualities? Maybe the MQM knew what most of us didn’t. In 1992, the state launched a concentrated military operation against the party. An operation against a party whose leader’s image had miraculously appeared inside a flower. Months after ZA Bhutto’s PPP came to power in December 1971, my father was an assistant editor at the party’s official daily Musawaat. He once told me that in early 1972, the newspaper received a photograph which apparently showed a fiery image of a sword in the night sky of Lahore. The image was sent by a leader of the PPP with a note saying that the day Bhutto had taken oath as President, the sword had appeared over Lahore. Not-so-incidentally, the sword was PPP’s electoral symbol during the 1970 elections. Musawaat published the picture and the news item. In 1974, the progressive Urdu weekly Al-Fateh — of which my father was one of the founders — received a similar image. This time, it was of a sword appearing over Karachi and that, too, at the conclusion of the famous International Islamic Conference that was chaired by Bhutto in Lahore. Even though Al-Fateh was a pro-PPP magazine, its founder-editors decided not to run the picture. Recently, social media was flooded with images of PTI chief Imran Khan’s picture projected on a tower in Saudi Arabia. Even though the image was fake, PTI’s official Twitter handle milked it, so much so that even some TV news channels ended up running the same image.

However, unlike the fantastical flower image used by the MQM and an ethereal one pushed by the PPP, the PTI used a more conceivable image. The mindset was the same though: Reinforcing a leader’s image with a larger-than-life claim. So, is this a tradition in our part of the world? There are very few examples other than the ones mentioned here where the qualities of political personalities are enhanced through some fantastical claims. Apart from some old books that made certain other-worldly claims attributed to a handful of 18th and 19th century Islamic scholars in South Asia, I could not find any prominent political examples in this context. However, it is clear that this tradition has a historical link with the phenomenon of deeply religious people ‘discovering’ miraculous signs. Over the centuries and even today, one comes across ‘news’ of people discovering blood pouring out from statues of Jesus in Catholic churches in South American countries, or tears trickling down from the eyes of Mary’s figurines in European villages. During my research, I found that in South Asia, sightings of Hindu deities consuming edible offerings left in Hindu places of worship by devotees appeared from the 19th century. This is also the period when Muslims in the region began to discover the name of the Almighty on fruit, vegetables and even goats!

In cognitive aspects of religious symbolism, Pascal Boyer suggests that, over the centuries, every time a population or a more religious segment of the population feels that the state of their faith is weakening, it tries to reinforce it among the people by proliferating miraculous claims. Interestingly, this phenomenon is not that ancient. Its frequency increased with rapid advancement of science and secular politics. The sudden appearance of Altaf Hussain inside a flower was born from the creeping fear in his party that the state was gearing up to neutralise it in Karachi. PPP’s sword in the sky was an attempt to give Bhutto’s otherwise ‘socialist’ regime divine approval. But Khan’s image photoshopped over a Saudi tower was a lot more ‘modern.’ It was done to exhibit how excited the world was about Pakistan’s new PM-in-waiting, even though he had emerged through a controversial election and with extremely fragile support in Parliament.

Writer: Nadeem Paracha

Courtesy: The Dawn

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)