If there is one major shift required in 2020 in the way India deals with its neighbours, it is to maintain a foreign policy that is bereft of short-term electoral considerations

The year 2019 was dominated by internal political considerations that impacted India’s relationship with neighbouring countries, which typically requires magnanimity, accommodation and beneficence for it is the dominant nation in the subcontinent and the region, too. 2019 was also the year when the 17th General Elections were held. Certain hardening of positions and postures by national parties, to the detriment of sentiments across the international borders, was inevitable given the high electoral stakes involved.

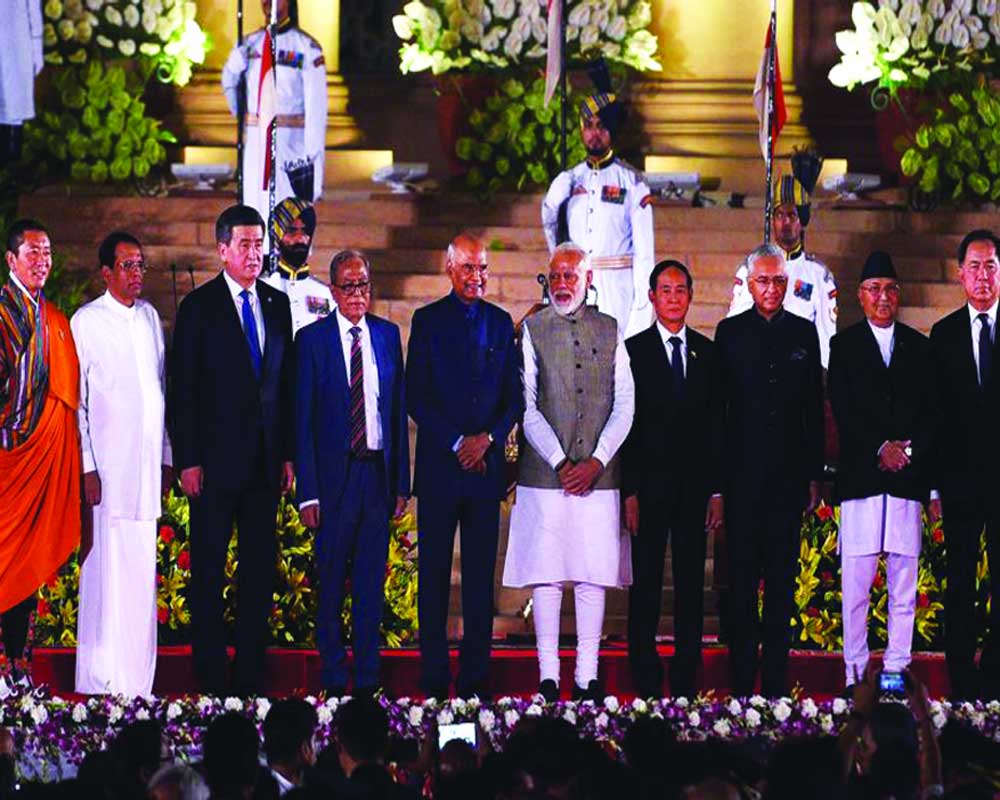

Earlier misadventures by Pakistan in the form of Pulwama had already foreclosed any possibility of rapprochement in the deeply-hyphenated realm of India-Pakistan dynamics. Besides the Pulwama-Balakot reciprocity and din, matters pertaining to neighbourhood affairs reached a low ebb in the months leading up to the elections in May. Post the polls, the surprise selection of former diplomat S Jaishankar as the Minister for External Affairs promised the much-needed statesmanship, maturity and domain knowledge to heal the simmering and unaddressed restiveness in the region. While it has been barely seven months since the new Government assumed office, neighbourhood relations remain a matter of grave concern.

The year 2019 was also the one when new Governments were formed in three key neighbouring nations. The year began with the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League registering landslide victory in Bangladesh. It is decidedly a more pro-India dispensation than a possible Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)-led by Khaleeda Zia, which could not even participate in the elections. What was even more reassuring to further India’s strategic concerns was the fall of the Abdulla Yameen Government in Maldives, which had worryingly forsaken its traditional “India-first” stance in favour of the Chinese. It was replaced with India’s traditional ally, Mohamed Nasheed-led Maldives Democratic Party (MDP), which made a comeback with a two-thirds majority. It won 65 of the 87 seats at the hustings.

However, India’s luck with the new leadership ran out in Sri Lanka with the return of the Rajapaksa clan in the presidential elections. The Rajapaksas, as it is known, have a pro-China legacy. Now, Gotabaya Rajapaksa has won presidentship and paved the way for Mahinda Rajapaksa to take charge as the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka. Riding on the wave of the Sinhalese ethnic-religious majoritarianism, which got instigated during the horrific Easter Sunday bombings, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the former military strongman with a questionable track, set alarm bells ringing in New Delhi with his ascendancy.

Relations with our neighbours in the East, like Myanmar and Bhutan, have remained robust with the continuation of the India-Myanmar Bilateral Army Exercise (IMBAX) and Naypyidaw’s support for the Indian armed forces in fighting insurgent groups based in Myanmar.

India’s measured response on the sensitive Rohingya issue with Myanmar and the evolving economic opportunities in treaties like the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), ASEAN and Mekong Ganga Cooperation have helped it maintain momentum.

India also seems to have struck a fine balance with Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD), the civilian Government, the still-powerful Army in Myanmar and even the erstwhile junta, with whom cross-border operations are facilitated. Bhutan’s strategic convergence with Sino-wariness (Doklam shadows still lurk) and the hydropower opportunities got a further fillip with the Sunkosh Project, which is four times the size of the 720MW Mangdechhu Project that was completed recently.

However, relations with Nepal remain less than satisfactory as China aggressively keeps baiting Kathmandu with development sops that are irresistible for the ideologically-aligned Communist regime over there. The counter-lever is openly flaunted in Kathmandu and the memories of the 2015 “Indian blockade” are not completely forgotten. The recently-updated and released map of India led to fresh controversy in Nepal on the inclusion of Kalapani. But it is the long freeze in the India-Pakistan relationship that seems irreconcilably poised with the odd Kartarpur bonhomie getting frittered away as there’s no forward movement happening.

Electoral politics on both sides along the Line of Control (LoC) are increasingly predicated on the ability of both nations to sabre-rattle, instigate and flex muscles at each other for short-term gratification. Neither side is willing to “risk peace” as that path is littered with perceptions of political weakness. Meanwhile, the Chinese are content playing with its “all-weather-friend”, Islamabad, and is ready to fructify its strategic China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor (CPEC) imperatives that will further beholden Pakistan to China.

The year 2020 will test India’s foreign policy mandarins. The serendipitous pro-India regime ushering in Male and Dhaka notwithstanding, the Chinese will continue bearing down in the region with an eclectic mix of charm (take the example of Nepal), development aid (example, Sri Lanka), coercion (example Bhutan), intimidation (example, Myanmar) and debt-traps (example, Pakistan) continuously wenching out neighbouring countries from improving stances with India.

The spirit of accommodation and optics of problem-resolution, that have been waning in recent times, have to be given top priority. Nepal and Bangladesh in particular, where murmurs of India’s political intransigence have gained credence. The recent hullabaloo over the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and National Register of Citizens (NRC) has raised concerns in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Concerted engagement to clarify and allay fears are urgently called for. Already, the Bangladeshi Foreign Minister called off his trip to India in the wake of these concerns. This has flagged potential red flags.

If there is one major shift required in 2020 in dealing with neighbouring countries, it will be to conduct foreign policy that is bereft of short-term electoral considerations. Recent accusations of meddling in Madhesi issues in Nepal, supposedly “influencing” Government formation in Sri Lanka and Maldives, unsettled riparians issue with Bangladesh — all are symptomatic of an unhealthy “big-brother” perception that New Delhi is increasingly getting accused of.

India has to posture neutral preference in the impending Myanmar National Elections in 2020 as these are sensitive times with a potential to damage sovereign credentials. Pakistan and China should not be expected to be resolved but only managed better. The subtle inclusion of international pressure via groupings like QUAD (US, Japan, Australia and India), UN watchdog bodies like FATF (it threatens to “blacklist” Pakistan on supporting terror) and increasing economic engagement with the Gulf Sheikdoms to neutralise the emotive and traditional Pakistan bias for them will be key in upping the ante with Islamabad without directly taking on the same. “Management” rather than “resolution” will necessitate realpolitik that aggressively taps into India’s “pivot” or “counter” status in a fractured world that stares nervously at the permutations and combinations that await the US presidential elections, Brexit and other geopolitical upheavals. These need to be put in a diplomacy calculus which is still managed professionally, unhindered and without an eye on domestic elections.

(Writer: Bhopinder Singh; Courtesy: The Pioneer)

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)