Television and its warts

by Hiranmay Karlekar / 17 October 2020The print medium has the responsibility of countering the socially and morally devastating effect of the deplorable fare that some channels are churning out

The character assassinations and defamatory campaigns, witnessed on some television channels by some anchors and reporters against individual film personalities and the Mumbai movie industry, have understandably been strongly condemned. While the public response has mainly been focussed on the campaign and its gross violation of the principles of fair play, there is a compelling need to examine the character of television itself as a medium and its impact on society.

As a medium, television combines unfolding visuals with verbal narratives, besides bringing distant events to the homes of viewers, giving them a feeling of being in the midst of an unfolding development or its aftermath, with all its sights and sounds. In contrast, radio, which provides only audio accounts, does not give the feeling of being there and seeing it all. Not surprisingly, television coverage attracts more people than radio reportage and provokes more intense public reaction than radio.

The question arises: What are the consequences of its impact? One frequently heard in the 1960s that television coverage brought the horrors of the Vietnamese War into American drawing rooms and was a major factor in triggering massive protest demonstrations and rioting, hastening the United States’ withdrawal from Vietnam. Why go so far? We are now witness to the investigations into the rape and murder of a 19-year-old girl in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh, in the aftermath of a nationwide uproar sparked principally by television reports.

Pieces in the print media — daily newspapers and magazines—have cost important people their perches. Newspaper reports have caused riots, violent demonstrations and general strikes, paralysing entire countries. This, however, was when newspapers and magazines constituted the dominant media. Now television has replaced them. This is the result not only of the pronounced edge that audio-visual reportage has over audio or print coverage, but of the fact that reports appear on television the same evening — or even earlier. An event has occurred, and by the time it is in newspapers the next morning, people already know the broad contours of what has happened.

There is, however, a fundamental difference in popular response to television and print medium coverage respectively. It lies in not just the actions they trigger but the mindsets they create. This, in turn, follows from a basic difference in the character of the two. Visual images constitute the USP of television. An image is recognised; the mental process involved in cognition. A printed word is first decoded from the combination of the letters that constitute it, and is then linked by a mental process —association — to an object or an image. The ability to associate is central to the process of rational thinking and the latter is the principal instrument in the formulation of systems of thought or critical examination of the import of events.

Cognition primarily involves visual identification. It is not an act of intelligence though it can lead to one when externally stimulated. Much depends on the nature of the stimulus. In Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, Neil Postman states that entertainment is “the supra-ideology of all discourse on television. No matter what is depicted and from what point of view, the overarching presumption is that it is there for our amusement and pleasure.” This is hardly surprising. A very large section of people wants entertainment. Hence programmes that entertain earn higher Target Rating Points (TRPs) than those that do not, and advertisers, who sustain media, also prefer these.

There are doubtless television channels that consciously try to tread a different path and come up with programmes that inform and promote socially and politically relevant discourse. But even their programmes have an ambience of entertainment as they are preceded, followed and punctuated by music and advertisements featuring visuals of attractive models and products in the most arresting possible settings. For example, the advertisement of a car or a motorbike often shows it in shining colours, driven by a beautiful model or her equally attractive male companion, through a picturesque landscape. People enjoy watching these, sometimes more than the programmes themselves.

This writer has no quarrel with entertainment. Life would be terribly boring without it. He also believes that each person is entitled to his/her brand of entertainment within the limits prescribed by law and a very liberal definition of decency. There is, however, a dark dimension to what is happening now. Viewers, who remain glued to television sets while some anchors, reporters and talking heads gloat over the travails of film personalities and berate them hour after hour, behave in the same manner as the crowds in ancient Rome’s Colosseum, who roared in delight as a gladiator killed another or a lion. By catering to them, the mindset that television engenders is that of wanting to be perennially and brutally entertained. The result is a progressive coarsening of sensibilities and erosion of the virtues of compassion, tolerance and a sense of fair-play.

This is the most detrimental effect of television as a medium that needs to be countered. The print media is a very different cup of tea. It is the outcome of the written culture. Alvin Gouldner states in The Dialectic of Ideology and Technology: The Origins, Grammar and Future of Ideology, that writing confers a permanence to statements that verbal articulation does not. He argues that it also confers a certain finality. A mistake made during a conversation may be corrected then and there. A printed word cannot be easily recalled for correction once widely circulated. One, therefore, carefully seeks to avoid mistakes, embarrassing statements and faulty arguments while writing. This contributes to the drafting of informed and reasoned texts.

Besides, while one can interrupt and resume a conversation, one cannot do so in a written text where one has to proceed from premise to conclusion, rationally and convincingly, step by step — a process that leads to rational articulation and critical thought.

Doubtless, written communication lacks the advantages that a speaker has at a lecture. He/she can convey a great deal through gestures, facial expressions and body movements; a listener/ viewer can also glean considerable information about the speaker and what he/she is saying and stands for. Equally, excessive focus on the speaker can distract attention from the substance of the speech. There is no such distraction when it comes to looking at a printed text. The reader can concentrate solely on the latter, absorbing its contents and reflecting on the same. Reading conduces to thought and thought spurs further thought. This fact, as well as the capacity for rational argumentation from premise to conclusion that the print medium promotes, has led to the rise of great systems of thought which have come to be known as ideologies.

That is another story. What is important now is the fact that the process of critical thinking can — and often does — mediate in a person’s internalisation of the information generated by the print medium. Given this and some other of its attributes, those associated with it have a responsibility in countering the socially and morally devastating effect of the kind of deplorable fare that some channels are churning out. The process must begin by making people aware.

(The writer is Consultant Editor, The Pioneer, and an author)

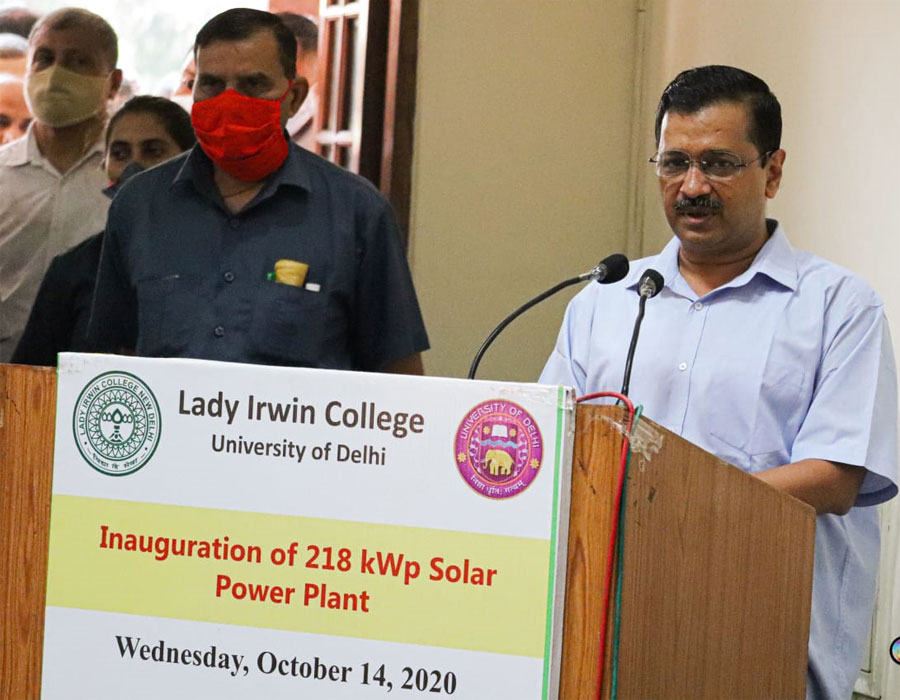

Inauguration of 218 kWp rooftop solar power plant at Lady Irwin College

by Opinion Express / 15 October 2020Lady Irwin College, established in the year 1932, is one of the oldest and most reputed institutions of higher education for women affiliated the University of Delhi. Leading the way to a sustainable future, the college is proud to have established a 218 kWp Solar Photovoltaic (SPV) rooftop plant on its premises, taking forward the Government of Delhi’s scheme for solarization of government buildings. The plant was inaugurated on 14th October’ 2020 by Hon’ble Chief Minister of Delhi, Shri Arvind Kejriwal. In his inaugural address, Shri Kejriwal thanked and congratulated Lady Irwin College for taking leadership role through this initiative of Delhi government. He said, “Lady Irwin’s initiative will not only motivate other institutions to go solar but would also contribute in making Delhi the solar capital of India.”

Emphasizing the college’s commitment towards sustainable development, Dr. Anupa Siddhu, Director, Lady Irwin College stated, “The founding members of the college have built a strong foundation based on core values of sustainability for achieving excellence in all spheres of life. Taking into consideration the effect of global warming, we felt it was time to shift our dependency from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy. The addition of this solar plant will not only fulfill our electricity needs but also help us reduce our electricity cost.” She praised and thanked the Delhi government, IPGCL and NDMC for making such enabling schemes. Dr. Meenakshi Mital, Convener, SPV project, Lady Irwin College reported, “the solar roof top project was conceptualized about two years back and subsequently we planned to go with IPGCL under the RESCO model. M/s. Oakridge energy was the empanelled vendor of IPGCL who undertook our project. The plant has been put up on three major buildings of college. The solar plant will generate about 3 lakh units of power each year and contribute greatly in Delhi’s fight against pollution”. Dr. Puja Gupta, Convener, SPV project, Lady Irwin College said, “the college has always been sustainable in its true sense and this project is going to take that legacy forward”. Dr. Gupta further thanked the hon’ble chief minister Shri Arvind Kejriwal and NDMC Chair, Mr. Dharmendra fro gracing the occasion with their presence.

The project was in the pipeline since last year wherein several visits were made by the installer to check the feasibility and the PPA was signed earlier this year. Dr. Meenal Jain, Coordinator, SPV project, Lady Irwin College who has been associated with the project since its conception and was instrumental in getting it installed appreciated the director of Lady Irwin College to have taken this initiative. She further said, “This SPV plant will not only cut down the emissions generated through the use of conventional grid-power, it will also set an example for others to go green”. She thanked Oakridge Energy, their development partner, for meeting the timelines for installing the solar plant, even during the pandemic.

The SPV plant has been installed and commissioned by M/s Oakridge Energy Pvt. Ltd. under the aegis of IPGCL, and has been net-metered by NDMC. Mr. Shravan Sampath, CEO,

Oakridge Energy praised the Delhi government and NDMC for their support. He said, “PPA has been signed for 25 years with the college and the solar plant will have immense cost savings over these years.”

Root for green products

by Kota Sriraj / 15 October 2020Whether electronics harm the environment or not depends on how environmentally accountable the manufacturer is

Most phone and high-tech companies globally are investing in environmental accountability. For instance Apple, which recently launched its new range of products, would be shipping them without the customary charger and headphones being included in the box. Though this might put off quite a few of its customers, it is part of the company’s commitment to reduce carbon emissions and ramp up the use of clean energy. With over 700 million headphones and two billion power adapters already out there with the customers, the firm has taken a bold measure to stop including the same in its retail product pack to cut down electronic waste generation at source and reduce carbon emissions, which are generated in the process of mining for precious earth materials. Moreover, due to the removal of the charger and headphones, Apple has been able to reduce the size of its boxes, enabling it to fit 70 per cent more boxes and, therefore, transition to a more effective logistics template. By 2030 the consumer technology giant aims to achieve net zero climate impact from its entire business, including manufacturing, supply chain and product cycles.

Samsung, too, is setting up new standards in conserving the environment through its “circular resource management system” that hinges on recycling, green purchasing from vendors amid effective hazardous material management. The company is focussing on reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) emissions to the extent of 70 per cent in the near future. Another global tech giant, Nokia, is redefining how products become more environmentally accountable. It calls this “Responsible Technology” and has gone a step further by joining 86 other like-minded companies to ensure that the strategic vision for the group is aligned with reducing the global temperatures by 1.5° Celsius in order to collectively battle climate change. This is in addition to the active initiative currently under way to completely remove single-use plastics across its production spectrum.

For a world that is drowning in electronic waste, especially in countries such as India where e-waste regulations are anything but effective, these firms are setting a benchmark in product responsibility and accountability towards the environment. However, they still have a long way to go since not all products end up getting 100 per cent recycled. The day they can recall their “end of life cycle product” back to the starting point for recycling is the day they can claim 100 per cent environmental accountability. However, their efforts are thought-provoking and make one wonder where do Indian companies figure in comparison? And why do none of the Indian-made products achieve such comprehensive environmental accountability? The answer lies in vision or the lack of it. Much of the corporate social and environmental responsibility in India is aimed at satisfying Government protocols and very little actually percolates to the ground level. One can still see the impact corporate vision has on some social project, but one is hard-pressed to effectively find an environmental project that has the stamp of a sincere corporate effort on it.

Indian manufacturing companies need to build a much-needed environmental dimension into their products. This is no easy task given the fact that sometimes even finding after sales service for many products we buy today can prove to be a harrowing experience. To graduate from this stage to a level where the companies produce a 100 per cent recyclable product is a long journey that needs encouraging policies and incentives from the Government and world-class corporate leadership. In this journey, innovative methods and ideas can lay the foundation for Indian companies to produce environmentally-accountable products. One of the initiatives that can be pursued is to create a category of “green” electrical and white goods which are made of 100 per cent recyclable material and have a clear-cut end of life cycle disposal plan. This category can be promoted and encouraged by the Government through tax and logistics sops besides finance options to manufacture them. On the consumer end, they can also carry compelling finance schemes or lucrative discounts. The clear environmental and viability-related benefits would surely drive manufacturing firms to increase their “green product” portfolio as it would also improve the company’s image and standing for being environmentally conscious. Similarly, the drive to produce at the lowest cost and sell at the maximum profit is the root of all evils because in the pursuit of driving down costs, manufacturers disregard all ecological concerns and use suspect material that is environmentally hazardous. Recycling then is impossible. Therefore, to give credence to the concept of “green products”, the Government must rein in the supply chain and third-party vendors for whom quality assurance and environmental responsibility are alien concepts. Surprise checks, quality control at Government laboratories and harsh penalties for defaulters can help infuse new-found respect for the environment. Products that we buy today continue to exist long after we dispose them. Whether they harm the environment or not depends on how environmentally accountable the producer is.

(The writer is an environmental journalist)

Man with many hats

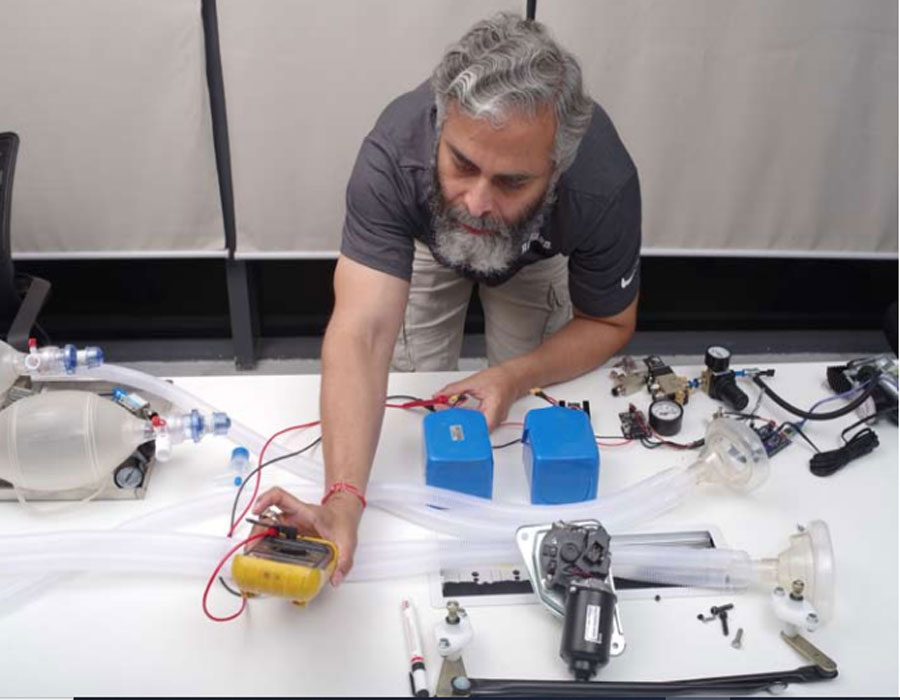

by Opinion Express / 08 October 2020Ravinder Pal Singh an award winning technologist, rescue pilot, angel investor all rolled into one

Ravinder Pal Singh shies away from attention, despite the fact that he’s one of the world’s most sought out experts in the field of Artificial Intelligence, Innovation and Robotics. Ravinder Pal Singh (Ravi), is an award winning Technologist, Rescue Pilot and Angel Investor with several patents. As an inventor, engineer, investor, highly sought global speaker and storyteller, his body of work focuses on making a difference within acute constraints of culture and cash, mostly via commodity technology. Ravi’s latest invention is arguably the world’s most affordable ventilator and what has fuelled him, in his own words, is – “Fear of human contact is not sustainable for civilization. Everyone has to contribute to overcome this fatigue and fatality of fear”.

His latest visionary creation is a blueprint to help humanity in the fight for survival against one of the most challenging health crises in the recent past. The impact of COVID-19 has prompted a reluctant but much needed change. According to Ravi, the cost of life should not come at the price of lifestyle. Intent for compassion has to translate into actual actions by everyone and every-where and every day. Disparity and im-balance take resources away from most people to live a basic life, so a minority can afford an expensive (lavish) lifestyle, and this is no longer sustainable. Secondly, the world, till now, has been driven by collaboration of conflict (potential of war) and/or economics (fiscal prudence), which should be changed towards collaboration to survive, keeping health as a priority. Healthcare infrastructures across countries needs to be revisited and global uniformity has to be established. Thirdly, how we design our lives places where we live, places where we work, places where we interact - should all change. The glorification of creating mega cities is no longer sustainable. In fact, the history of the demise of past civilizations has a commonality of 4 factors: A combination of an epidemic plus population movements plus the pressure urbanization put on rural lifestyles as well as climate change. There is still merit in non-political Gandhian theories based on De-centralization and Micro Markets, Rural development (ideal cluster of villages), Self-sufficiency while living harmoniously with nature and a greater equity or “distributive justice via creating institutions than solely profit driven businesses.

The inspiration for Ravi’s latest invention came from his own experience at the frontlines. The world faces a severe and acute public health emergency due to the ongoing COVID-19 global pandemic. It is a stark truth that COVID-19 can require patients to be on ventilators for significant periods of time and that hospitals can only accommodate a finite number of patients at once. Ventilator shortages are an unfortunate reality as the COVID-19 outbreak continues to worsen globally. Ventilators are expensive pieces of machinery to maintain, store and operate. They also require ongoing monitoring by health-care professionals. To solve the above situation, Ravi has invented and prototyped an affordable ventilator for all, using a minimalistic design which can be easily operated by anyone. The key design element is the ability to build it quickly for mass production so governments around the world can encourage existing industrial setups and start-ups to manufacture them locally to help save lives.

Ravi was baffled with the thought of why one would require an engineering degree to design, produce and manufacture a ventilator. He has built two different working prototypes on common platform design. The first version is the simplest and is an extremely portable ventilator, one which is intuitive, can be used by anyone and fundamentally takes air from the atmosphere, extracts oxygen, controls pressure and pushes the output to the lungs. The second one is an advanced version of this particular ventilator. It is on a similar design plat-form which converges artificial intelligence with electrical, mechanical, electronics and instrumentation, with the capability to supply pure oxygen. It has self calibration capabilities, a machine learning algorithm to adjust the air flow according to the needs and the resistive nature of the lungs of any patient. Both of them are based on common platform design thinking and that’s the real beauty of his patented design and platform thinking. The reason to work and produce outcomes has become purified through the stark reality of death. Driving Ravi’s imagination and the core to all of his inventions is the burning desire to create a meaningful body of work through compassion oriented design and architectural forms.

Ravinder Pal Singh (Ravi) is a Harvard Alumni and Award Winning Engineer with over several hundred Global Recognitions and Patents. His body of work, mostly 1st in the world, is making a difference within acute constraints of culture and cash via commodity technology. He has been acknowledged as one of the world’s top 10 Robotics Designers, #1 Artificial Intelligence Leaders in Asia and featured as one of the world’s top 25 CIOs. Ravi is the advisor to a board of nine enterprises where incubation and differentiation is a core necessity and challenge. He sits on the advisory council of three global research firms where he contributes in predicting practical future automation use cases and respective technologies.

Established in 2016, Annie Koshy Media Consultant has developed a reputation for expertise in Media Relations, PR and Promotion of those in the arts, media and entertainment industries, as well as in Marketing and Community Outreach. The multi-award winning media brand, has a vast network, both within the South Asian as well as the mainstream communities and has the leverage to develop meaningful associations amongst individuals, businesses and within the media fraternity. (www.anniejkoshy.com | www.findyourselfseries.com)

Facebook vs Delhi

by Opinion Express / 24 September 2020The technology major is like a media company and should be subjected to similar laws

Facebook should be answerable to Governments as the technology giant can fundamentally alter the course of public discourse not just through its own network but through other assets like messaging application WhatsApp and photo-sharing application Instagram. These are all powerful tools to build organisation and opposition but can also be used to silence dissent or manufacture violence. The safe harbour provisions under which such technology companies have escaped sanction for many years cannot be allowed to continue unchallenged. The likes of Facebook and Google are not just technology companies, they are media companies, too, and should be subjected to similar laws. Technologies like deepfake videos, where even a few photographs can be used to manufacture a video showing a personality spouting opinions far from his/her real stand, can potentially alter the course of a democracy. Think of this as the new terrorist attack before an election. By the time any rectification takes place, often due to delays, the damage has been done.

We agree that it is impossible to keep a check on every single user at every single point of time. However, it is also true that technologies are being developed to be able to quickly find potential hateful content. That said, it is important to haul these companies under the Central Government and on that front, Facebook India does have a point in refusing to appear before the Delhi Government’s Peace and Harmony Committee. The company is currently being hauled over the coals in a parliamentary committee, not just in India but in several countries across the world as Governments realise that its power needs to be kept in check for the growth of democracy. This includes the United Kingdom and the United States. Indeed, we wish the parliamentary committee hearings in India were streamed live for the public to observe and decide for themselves. Tech majors can do more themselves. For example, they should work a lot closer with traditional media companies as well as develop technologies that can easily detect videos that promote hate as well as those where users threaten self-harm. Facebook should not be allowed to escape with impunity but making it answerable to multiple agencies will serve little purpose either. Indeed that could actually delay meaningful reform.

(Courtesy: The Pioneer)

The intelligent future is here

by Kumardeep Banerjee / 18 September 2020Events of 2020 have hugely accelerated the human civilisation’s race towards finding an alternative to its own organic intelligent brain

Now that most of us are becoming video-conferencing experts, innovating on every call with a new virtual background, while also ordering groceries online and keeping an eye on the latest news updates popping up on our phone and computer screen, will it be too early to crystal gaze into a not-so-distant future, say 2021? Yes, it may be too early to call 2020 a “gap year”, specially when each new day has its own set of surprises. But there is no harm in peeping a little into next year’s trends. First, there is no escaping the fact that technology will tremendously impact the way we live, work, exercise, eat or buy next year, too. If the pandemic has thrown us into an ocean of uncertainties, if we look around carefully, it is an ocean of data. Those that learn to swim through pretty quickly and get a raft or something to latch on to will soon realise the potential of this ocean of opportunities. It has already started happening but a new technology called Artificial Intelligence (AI) will take over most of what is today relegated to a digital world.

To start with, algorithms would be put to use for early detection or even prediction of pandemics, assessment and even solutions for traffic patterns in a city, incremental/severe weather forecasts, healthcare, care for the most vulnerable and so on. But soon, like everything else, it will be all-pervasive in every little life decision. I am not sticking my neck out to say it will happen by next year but events of 2020 have hugely accelerated the human civilisation’s race towards finding an alternative to its own organic intelligent brains. The world is already flush with examples on how AI will have multiples of applications from that which is already available across the web. In short, we are on the verge of entering a new technological era which is predictive, sophisticated and has an eerie inorganic intelligence almost running into infinity (it is not enough to cut the cord and think that an AI system has switched off; remember there are thousands of machines crunching data points from multiple sources to predict simple buying behaviour). This will definitely have a deep impact on the human race.

Next will come an age of extreme speeds of data access over the air or 5G. The world would have already been piloting cutting- edge 5G or fifth-generation mobile technology across large geographies and would have been near phase-wise national rollouts, had the pandemic not hit. India definitely has lost a year in the 5G race. However, the protocols and network vendor partner solutions may have been made more secure as a result of the delay.

In fact, 5G is likely to see the first level of deployment in urban areas (where the revenues are) and besides helping you download (at say five times the speeds of your current streaming action) social media videos/your favourite films and cricket matches, will also prove to be a great tool for remote and risky jobs. If some of the arterial sewer lines in a city are fitted with 5G chips, there could be a possibility of completely eradicating the need for human intervention in maintenance of a city’s drainage system. If the data coming in and also fed into the chips are analysed at the back-end by smart machines (think AI), who, then takes decisions to deploy little machine worms into the sludge to clean a choke or fix a leakage or even defuse a toxic gas emission, it would mean saving a few thousand precious lives each year. Together with this will come the ultra-smart homes (the protocols for which are already in advanced stages of negotiation by big tech companies) where perhaps your cooking burner will decide the menu and your bar may order itself a few of your favorite wines in case you aren’t stocked for the weekend. While robotic surgeries performed over the network specially for remote terrains (read rural) are already happening outside India, a self-driving car in Chandni Chowk may be further away.

Now that the all-pervasive technology has started to co-exist with us in our altered carbon realities, the threats to humanity will also increase. These threats would be increasingly cyber and 2021 will likely see more cyber security attacks (small, big, macro) than all of these years of digital revolution put together. The tell-tale volumes of these cyber security attacks (think SIM cloning, phishing attacks, stealing of bank passwords and OTPs) are already giving consumers and lawmakers a nightmare with increased adoption of the digital world during these work from home times. Think of the manifold increase of these forces as the technology world starts getting more complex with evolving protocols and appendages. You are more likely to hear the word cyber security in almost every important public forum and ministerial dialogues than you have ever heard in your life. Along with these, and one can only wish, multilateral solutions to tackling emerging threats will also emerge, which prevent anti-State forces from manipulating users of emerging technology. There will be new policy regimes, language and grammar for embracing these brave new islands we are heading towards, but let’s keep those for a later piece.

(The writer is a policy analyst)

Mitigate data intrusion worries

by Ripu bajwa / 17 September 2020Instead of thinking of security as a prevention tool, firms must incorporate it into product design from the start so that the architect systems are impenetrable

In the new digital era, where data is growing at an unprecedented rate by the second and where organisations are quickly becoming data-first, one thing has become crystal clear. That the “this is good enough” approach by businesses, across the globe and in India, is no more acceptable when it comes to safeguarding the most precious capital, i.e. data, from an external intrusion. Ever since businesses have become increasingly dependent on their data to fuel innovation, drive new revenue streams and so on, Information Technology decision-makers have not just been evaluating their current data protection preparedness but have also been ramping up their investments in this regard.

However, over the past few months, since organisations have been fixated on quickly transitioning towards remote working due to the Coronavirus pandemic, they might have missed out on something vital that they should have been focussing on and that is the threats that come along with this work culture. As a result, the world and India with it, has been witnessing a steady uptick in the instances of cyber attacks.

For example, as per a recent report, India witnessed a 37 per cent increase in cyber attacks in the first quarter of this year as compared to the last quarter of 2019. The data also show that India now ranks 27th globally in the number of web-threats detected in the first quarter of this year as compared to when it ranked on the 32nd position globally in the fourth quarter of 2019. India also ranks 11th worldwide in the number of attacks caused by servers that were hosted in the country, which accounts for 22,99,682 incidents in the first quarter of this year as compared to 8,54,782 incidents detected in the fourth quarter of 2019, says the Kaspersky Security Network report.

Another report claims that data of over 21,000 Indian students, including their Aadhaar cards, photos and so on, have been put on sale on the Dark Web. Another instance of data being leaked on the Dark Web came to light in June, with a massive data packet — nearly 100 gigabytes in size — being put up for sale. The data comprises scanned identity documents of over one lakh Indians, including passports, PAN cards, Aadhaar cards, voter IDs and driver’s licences. Thus, given the rising data security concerns and incidents, chief technology officers (CTOs) need to look for a holistic approach towards data protection and management. Now, they need to be cognisant about how to respond, recover and learn in case a cyber intrusion occurs. Here are a few tips for CTOs that will help them redefine their data protection strategy.

Drift away from security to resilience: With the evolving nature of cyber attacks, it’s time for businesses to stop reacting and start anticipating. Loss of critical data has the power to not just cripple a company in no time but also damage its reputation for the long-term. Hence, instead of relying on traditional methods of data security i.e. identify, protect, detect, respond and then recover, organisations must imbibe state-of-the-art resilience strategies i.e. learn, respond, monitor and anticipate.

Adopt a security strategy ingrained in product mindset: Businesses must not only think about making security intrinsic to technology infrastructure but also aim at enabling security professionals become intrinsic to future product development. They need to transform into a data-first and product-first mindset organisation in order to be able to remain competitive in the future. Thus, instead of thinking of security as a prevention tool, the need of the hour is to incorporate it into the product design from the beginning so that it will make the architect systems and processes impenetrable.

The key to a winning strike is the right digital partner: In the past, businesses have been using a hit and trial method with regard to choosing their digital partner and this approach has brought in more vulnerability to their sensitive data assets. As per a report by Vanson Bourne, organisations in the Asia Pacific and Japan, which were relying on more than one data protection solution provider, were almost four times more vulnerable to a cyber incident that prevents access to their data. Hence, in order to combat the external threats, businesses must choose a single technology partner that delivers multi-platform security.

While it is critical to invest in the right technologies, it has also become utmost important for businesses to ramp up their education and awareness levels to stay abreast with new security threats. Therefore, to end the constant tussle between finding the right data protection architecture and keeping up with the modern security approaches, CTOs must focus on strategies that redefine their data protection ecosystems from time to time.

(The writer is Director and General Manager, Data Protection Solutions, Dell Technologies)

ICT unshackling subalterns

by Mohammad Irshad / 14 September 2020Is the information society selling a justifiable hope for liberation and empowerment to the marginalised in post-truth India?

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are providing an enormous platform to re-arrange societal contours, by abandoning the primitive, time and space-driven edifices of epistemology to develop some new sets of normative standards, for citizens in the information age. Citizenship assumes geography, which is later underlined as a nation-State. This understanding, however, becomes inept in times of a new digital citizenship under the sovereign ruling of ICT. This has paved the way for the subaltern’s voice. For ages, socially-acceptable and prestigious spaces/institutions were devoid of subordinate voices. Digital social media platforms via the internet have considerably enabled them to mature a first-hand collective consciousness to authorise a distinctive, shared philosophy (through Facebook, WhatApps, Twitter and so on) deeply interwoven in democratic traditions.

Digital windows have arguably helped diverse online communities to materialise their life-world experiences and advance a fresh alternative and corresponding model of living. Information society theorist Manuel Castells recognises the liberating outcomes of ICT. Subalterns are taking epistemic responsibilities in socio-technical processes of the information society, conditioned on epistemic justification to rectify injustice done to them.

ICT and empowerment: Subalterns have utilised digital platforms more suitably to reveal their experiences, ideas, concerns and aspirations and explore unsung heroes, weave stories and preserve oral traditions. These include their life experiences, cultures, traditions, beliefs, languages and ethics, despite the anxieties from the existing dominating political entities. Information technology enabled subalterns with the required information, without much obstruction, to get closer to the pursuit of truth and justice. Information/knowledge systems of a large section of the Indian population possibly would have been isolated by the mainstream content drivers to sustain dominant conceptual accounts and discourses/narratives. Meanwhile, cyberspace is offering sizeable avenues to freely communicate with local and globalised communities.

The rise of multiple online news outlets, individual content providers and senior journalists devoted to maintaining the integrity of their profession, and their incessantly digitally-widening audience, attests to the fact that subalterns and ordinary citizens receive more reliable information from them than from mainstream news outlets. In the present scenario, formal education is less required to produce creative content. On the contrary, industrial society is engrossed in ownership of talent. The information age does not need a bulky investment of academicians for information; rather it independently cultivates a new digital forum. It is also not purely social-capital caste driven. In this way, the creator of information will enhance balance in society. The embryonic subaltern epistemology adheres to different ideas and figures, which might be in stark contrast to some widely-considered knowledge structures. This will actually induce those, who remained at the helm of social and political affairs/narratives, to incorporate burgeoning criticism and demands of subordinates to enable the substantial democratisation of ICT.

Subaltern news outlets: Subaltern presence is notable in online news portals, though not adequately enough. Some channels like Dalit Dastak, National Dastak, Bahujan TV, National India News, The Shudra and Dalit Camera: Through UnTouchable Eyes have started generating content. They have subscribers/viewers in millions from various social groups. Notably, subalterns have utilised digital media to constructively choose relevant, valuable and meaningful information, more than ever to educate themselves.

ICT and subaltern causes: With collective struggle, subalterns are reaching at the centre of democratic knowledge production and content generation, challenging the discriminatory and hegemonic patterns of the State. The April 2, 2018 mobilisation of Dalits and Adivasis across the country, against the dilution of the provisions of the SCs/STs (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, is a unique testament to a better and purposeful utilisation of internet technology by subalterns in India to assert their rights. Leaders became irrelevant and, despite that, it could become the largest unprecedented movement of this scale, in recent years, by subalterns.

Why is information society more liberating to subalterns? In agricultural societies, they could not acquire the land. On the contrary, in the information society, they could secure key positions from content generators to content managers and owners. However, the lack of financial resources limits them from projecting their accounts as general mainstream opinions. At the epistemological front, they have had considerable accomplishments by acquiring digital space but do not possess materialistic resources to take the ownership of big mainstream media. The information society, further, has been converted into a revered room that furnishes more substance of respect and dignity to an ordinary subaltern. Fundamentally, the information society is based on ideals of inclusivity, mutual collaboration, open and free access to reliable data. The subaltern people’s reliance is diminishing on mainstream news channels. This will further translate into the development of community-owned and driven online media outlets, leading to active involvement and participation of outcasts and subordinates. More so to democratise the media space in the information society.

Subaltern hyper self: In an information society, people use the new social channels (Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and so on) to self-broadcast (uploading pictures and locations), reveal preferences (likes and dislikes), and share personal information (relationship status). This way they are developing informational selves, covering various aspects of human life.

Anonymous social identities and the idea of self could be reformulated on a digital platform to generate meaning and accomplish freedom of speech in society. Thai philosopher Soraj Hongladarom in his seminal work, The Online Self, maintains “viewing the self as made up of information makes it easier to account for the self in the online world.” The online self allows this unique opportunity, to conceal and change your identity to put your message across. The physical self, which is socially neglected, might form a new online identity (or social self) to legitimise itself socially, without revealing the original identity. The new online structure changes the forms of earlier social structures.

Futurist Jason Ohler argues, “Our ability to hide our real life identities by using obscure user presences — from chat room names to avatars who look nothing like us — allows us to literally reconceptualise ourselves.” It testifies the departure from the earlier mode of existential self to the digital self, which is attributing more meaning to a digital subaltern self.

Indian and Western digital self: Culturally, individuality is not suppressed largely in the West due to an individualistic understanding of the self, rooted in the Cartesian self. In India, desires, fantasies and aspirations are peculiarly anchored by external factors other than an individual. People will, therefore, often go and create digital selves and put fake/distorted/misinformation about their identities to cherish what they always wanted to be without revealing much about themselves. It has given them more freedom to express, which has resulted in the online social selves dominating the real ones. Sometimes, the social self overpowers the real existential self. In general terms, humans are living in a world of “double social self.” The former springs from physical social space, the latter is caused by ICT and made compulsory due to economic and political compulsions. Novel digital subaltern metaphysics has yet to be thoroughly comprehended in India. It could empirically be concluded that the information society sells a justifiable hope of liberation and empowerment to subalterns in India.

(The writer is Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi)

Game over

by Opinion Express / 04 September 2020The ban on gaming app PUBG might not make the Modi Govt popular with kids but it can spur local development

The events of June 15 in the Galwan valley of Ladakh have had some repercussions on the lives of millions of Indians and not just on those bravehearts who were mortally wounded in the battle. That clash changed our bilateral dynamic forever. It taught Indian policy makers that the Xi Jinping-led Chinese administration was not a good faith actor and would continue its territorial imperialism. Its continuous pushiness in Ladakh is proof enough. It spurred India, which had been lackadaisical in the development of infrastructure in border areas, to dramatically ramp up building activity. The embryonic ‘Quad’ alliance between India, Australia, Japan and the US got a growth spurt. It woke us up to the need to gradually withdraw our trade dependencies and shrink Chinese revenue at the expense of our markets. And it also allowed Indian policy makers to realise the level of Chinese influence in the mobile and internet arena in India. The ban on popular application TikTok and several others was just the start. Now the Indian Government has also taken down the popular gaming application, Player Unknown: Battlegrounds, usually called by its acronym PUBG, citing security and data privacy issues. Much can be written about the ban of these applications but as internet-entrepreneur Sanjeev Bikchandani explained on the first episode of The Pioneer Conversations, the national security establishment would have made this decision, taking into account all major factors. Data pilfering is a concern but yes, this is a punitive cyber counter-strike against Beijing, hitting it where it hurts most, namely its growing applications and tech penetration in India. In fact, Beijing implied as much, saying India had imposed the ban in the face of pressure from the US, with foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying warning against “short-sighted” participation in US restrictions against Chinese technology. India’s strategic shift to the US is becoming more pronounced and with the combined US-India blackout of Chinese tech access, the dragon could be impacted quite a bit.

Several of these applications had a vast majority of their users based in India and thus their valuations were powered by us. However, there are questions on the creators of PUBG, although its beneficial ownership is by Chinese firm Tencent. If the government chooses to target Chinese ownership, that could become a huge problem for several Indian start-ups, including PayTM, which has significant ownership from the Alibaba-controlled Ant Financial. The lack of Chinese money would make it difficult for some Indian start-ups to raise resources although it might make life easier for Indian investors. Thankfully, PUBG has pushed the live game streaming industry in India with a large number of content creators earning good money. Then there is another aspect to the latest ban which impacted several games and not just PUBG. What effect will that have on India’s nascent e-sports craze as well as game creation? We have been a laggard in the latter, and while there were tens of TikTok clones within hours of that app being banned, no Indian company is in any shape or form close to creating a reasonable gaming experience for users. That said, the burgeoning popularity of games in India and worldwide, the only entertainment sphere that has grown exponentially globally during the lockdown, might mean that there could be some good games being created in India in the coming years. This move could, in fact, goad game developers into innovating their products. However, bans work both ways and a ban on Chinese-created or owned games in India might mean that Indian-created games will also find it difficult to expand into new markets going forward.

Telecom price wars

by Opinion Express / 03 September 2020Is it a case of strangling the golden goose? Have corporate raiders profiting from public goods been stopped?

There is little doubt that the Indian telecommunications industry has transformed the lives of Indians and has done so at a price, to the final consumer, of pennies. Once upon a time, an outgoing call cost over 32 rupees a minute and data cost a hundred rupees for a megabyte. Today, mobile services are so affordable that many consumers don’t think twice about placing calls or downloading videos. In fact, data is so cheap that some consumers prefer mobile data or fibre-optic cables coming into their homes. But were the cheap prices all based on a ruse of cheating the Government out of revenue? That is what the Government claimed and won a victory in the Supreme Court in the now famous “Adjusted Gross Revenue” (AGR) case.

The telecom companies fought hard to ensure that payments are made over an extended period of time rather than in one go, which was also fair on the face of it. Now that the issue has been settled, what next for Indian telecom companies? They will need to raise billions of dollars to pay these fines and it is unlikely that they will manage to drastically raise access prices, although that might be the only solution. For far too long, India has operated on the basis of the “long tail” where low-income consumers make up a huge volume thanks to low prices. This has enabled low-cost invention but has stifled innovation to a large degree. India really needs to raise its median income higher and a constant focus on low-cost jugaad will not help, so higher prices might be the only way forward.

And those will be needed if India needs the next generation of telecom technology, 5G, which will dramatically increase access speeds and could be the backbone of Narendra Modi’s much-ballyhooed “Digital India.” India doesn’t want a monopoly in the telecom space and it needs the latest technology as well. Higher prices might be frowned upon by some in the government but they have gotten to the cake. They can’t keep on admiring it anymore.

Editorial: The Pioneer

Facebook in the dock

by Opinion Express / 18 August 2020Hitting a wall in China, the social media giant has played panderer to deepen its market in India

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg had once said that opinions aired on social media do not shape people’s choices, their lived experiences under a particular political regime do. Since then, much water has flown under the bridge and social media has not only been used as a propaganda tool but has been weaponised to create a wave of opinion and manipulate public perception. Russia was first accused of data mining, hacking and using details to influence the US election. After that, social media became such a powerful barometer of discourse that willy-nilly it has become a partisan tool. So it comes as no surprise that an article published in The Wall Street Journal on Friday stated how Facebook India “took no action after BJP politicians posted content, accusing Muslims of intentionally spreading the Coronavirus, plotting against the nation and waging a ‘love jihad’ campaign by seeking to marry Hindu women.” The report quoted a former Facebook employee as saying that Facebook India was told not to filter extreme Right-wing messages by BJP leaders as that would be inimical to its business in India. This is a serious allegation as it makes Facebook equally guilty of differential standards when it comes to hate speech and blots its claimed ethics of being an accessible platform for all kinds of issues. Worse, it makes Facebook look like a panderer of the establishment, more interested in holding on to its Indian market with 290 million users and another 400 million on Whatsapp. With China erecting a wall against Western platforms, the corporation looks desperate to consolidate its presence in India. But as usual, this concern, despite a series of denials by the company, got buried in the competitive whataboutery of political parties. As Congress leader Rahul Gandhi claimed vindication, BJP leader and Union Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad reminded him how the Congress itself had harvested data in alliance with Cambridge Analytica before the Lok Sabha elections. Many Opposition parties, too, had accused Facebook of being the BJP’s de facto campaign manager before the Lok Sabha polls.

The larger question is, therefore, can social media ever again claim to be an open platform of free-flowing speech and ideas, considering it has gotten deeply embedded in all aspects of our life and cannot but be an influencer in itself? Facebook and Twitter are two corporate giants who can wield information as power, with the former having snapped up rivals Instagram and WhatsApp in recent years. With over 2.3 billion monthly users across its networks, it is too much of a behemoth to be democratic. Some estimates say that internet users spend an average of two hours and 22 minutes a day on such platforms, giving political parties the power to harness the numbers and attention span to disseminate their ideologies and even dump them indiscriminately, picking up some stray attention, too, in the process. US President Donald Trump was calculated to have utilised Twitter for an estimated $2.2 billion of free media coverage. Even newer political leaders from the opposite end of the political spectrum have captured popular imagination because of their online presence. For the corporations themselves, they are not non-profit and will, in the end, look out for their revenue graphs than the greater good. And, therefore, are into a lot of self-serving governance protocols in the absence of a public propriety code. In fact, Nick Clegg, Facebook’s VP of Global Affairs and Communications, had commented last year that “we don’t believe … that it’s an appropriate role for us to referee political debates and prevent a politician’s speech from reaching its audience and being subject to public debate and scrutiny.” The problem with this uninvolved approach is that politicians are emboldened to do whatever it takes to get their viewpoint across, even lies. Because there is no fact-checking, a campaign can go viral — sometimes tidal — before it can be called out. Any rejoinder or retraction then seems rather pointless. Besides who would prevent mainline politicians from lying about their own data, which they quote citing their own statistical sources? No wonder the misinformation has catastrophic consequences though stakeholders benefit in their limited domain. There’s undoubtedly a need for a middle ground than a mutually self-serving club of the information propagator and the disseminator. Also such is their combined monopoly that while Facebook made money from paid political advertisements in the last US elections, Twitter capitalised on the anti-Facebook rant and banned such campaigns, drawing the alternative traffic to itself. Either way, both parties are capitalising on their database, a heaving monster that is beyond anybody’s control, and apportioning it between themselves. And users continue to be a captive audience.

Courtesy: Editorial-The Pioneer

FREE Download

OPINION EXPRESS MAGAZINE

Offer of the Month