Bid to whip up angst against farm laws abortive

by Narendra Singh Tomar / 01 November 2020Disagreement in politics is the right of the Opposition, but playing with the future of farmers is not healthy politics. Those swayed by the cry of the Opposition should question the Congress whose 2019 LS polls manifesto promised to abolish the mandi Act and remove ban on inter-State trade in agricultural produce

Thanks to our Prime Minister Narendra Modi for taking revolutionary steps to improve the agriculture sector and to provide new opportunities to farmers for their prosperity. The farmers got freedom from many legal restrictions and we have moved strongly towards the Prime Minister’s determination to double their income.

These reforms were needed for a long time, but despite hollow promises, the previous Governments could not muster courage to implement them.

Today, those who have questioned the reformative efforts of the Government should be asked why they could not take any major and important decision in the interest of farmers even after ruling the country for six decades. Was their political compulsion behind this or some other reasons?

Efforts are being made to create an atmosphere of confusion in the country regarding the minimum support price (MSP). The canard of discontinuation of procurement by the Government at the MSP is being instilled in the minds of the uninformed people.

Also, it is being said the farmers will have no option but to sell their produce outside the market at less than the MSP. First of all, I would like to correct the misinformation. We have clarified many times that the MSP declaration will continue and the Government procurement on the MSP will continue in the future. The MSP or procurement at MSP has nothing to do with the new legislation. Those who question the Government regarding the MSP should know that only after the formation of the NDA Government under the leadership of Modi, the MSP is being determined by adding at least fifty per cent profit to the cost the produce, as per the recommendations of the Swaminathan Committee. The Government of India declares the MSP of 22 crops.

One of the biggest outcomes of agricultural reforms in the country is that for the first time after Independence, farmers have got freedom from the clutches of middlemen. Till now the farmers were obliged to sell their produce in mandi and only about 30,000 to 40,000 licensed traders doing business in the mandis across the country used to fix the prices of the produce.

Through the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, farmers have not only got freedom to sell produce anywhere, but in today’s technological era, a more convenient mechanism has been created to sell produce through e-trading. Through this agrarian reform, the farmers can also earn more profit on their produce by saving tax and transportation costs.

The question is being raised again and again that the new provisions will abolish the Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMC). Here again, I want to make it clear that the APMC mandis will continue to work. The only difference is now farmers have freedom to sell their produce outside mandis also. These amendments will also provide an opportunity to the mandis to develop their infrastructure and farmers will get more facilities.

Similarly, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 aims to connect farmers directly with traders, companies, processing units and exporters. The farmers will get remunerative prices in every circumstances as the price of their produce is fixed before the sowing through the agricultural agreement.

Here, I would also like to clarify that the farmers will get additional benefits under the terms of the agreement along with the minimum price. The confusion is being spread that the land of the farmers will be handed over to the industrialists and traders. On the contrary, the truth is that in contract farming, there will be agreement between a farmer and a businessman to assure the price of produce at least at MSP. There is no issue of land in this case. No trader can take loan on a farmer’s land nor can any recovery be made against the farmer’s land. This law protects the interests of farmers in a much better way than the existing contract farming act of the States.

Provision has been made to make payment of produce to the farmers within three days of sale. Simultaneously, it has also been provisioned to settle the dispute at the local level within 30 days to preclude court cases. With this step of the Government, farmers will be protected against the risk of price fluctuations in the market due to fixation of the price of the produce before sowing. Along with this, farmers will be able to access state-of-the-art technology, advanced manure, seeds and equipment.

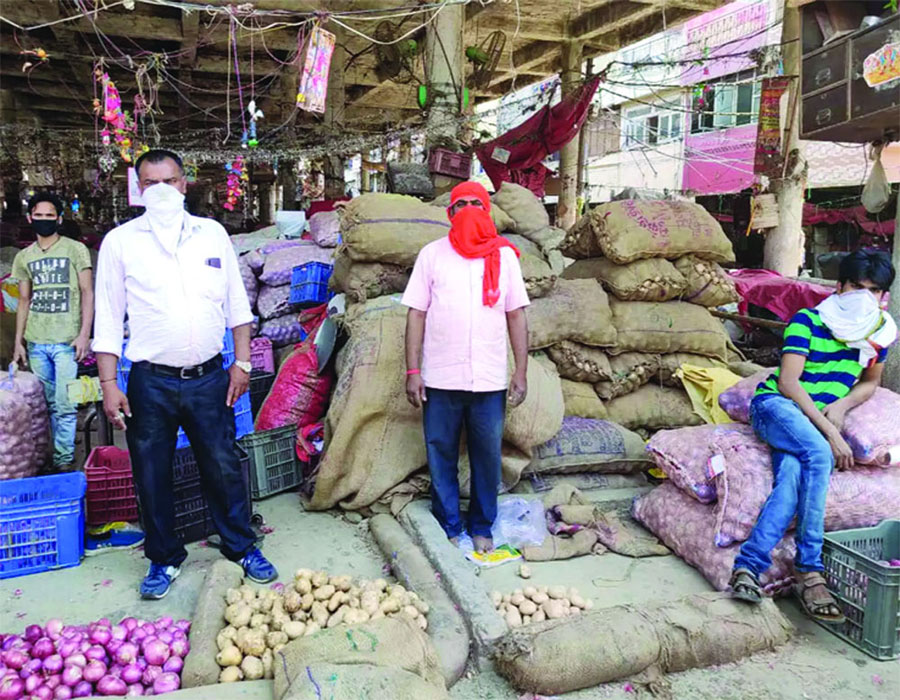

Under the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020, a provision has been made to remove grains, pulses, oilseeds, onions, potatoes, etc, from the list of essential commodities. This will increase the capacity of storage and processing and farmers can sell their crops in the market at a reasonable price.

Till now farmers have been worried about the loss of perishable crops like potato and onion. With the new provisions, the farmers will be able to grow these crops with more confidence. The canard is being spread here that hoarding will increase and traders will earn profits by selling products at inflated rate. This apprehension is unfounded; the Government has retained control of the stock limit as before on increasing the price beyond a limit.

Disagreement in politics is the right of the Opposition but for that, one should not play with future of the farmers. Those swayed by the cry of the Opposition against the revolutionary farm laws should verify facts and read the manifesto of the Congress in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections that promised to abolish the mandi Act and remove ban on export and inter-State trade in agricultural produce.

In the same manifesto, they had promised to establish farmers’ markets in big villages and towns to provide freedom to farmers to sell their produce. In the same manifesto, the assurance of amendment in the Essential Commodities Act was made. When the same issues are covered in the new provisions, the moot question is why the atmosphere of confusion is being created by protesting against the same.

Today after a long period, a serious effort has been made in the interest of farmers and for improving their condition. Full provision has been made in these Acts to ensure that farmers get remunerative prices for their produce and all their interests are protected. I will ask political parties to think once again in the interest of the farmers and the nation before whipping up a false opinion.

(The writer is Union Minister, Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Rural Development, and Food Processing Industries)

Innovative farming needed to combat climate change

by Kota Sriraj / 29 October 2020Food production is critical to keep the wheels of the economy turning. We must not allow climate change to hijack our food security

The rapidly worsening condition of the environment is increasingly creating harsh terms for agriculture in India. The sudden floods, such as those experienced by Telangana last week, and unexpected droughts in many areas coupled with a sheer drop in yield per acre are creating financial havoc for the farming community. Moreover, the recently-passed farm Acts have added to the woes of the already burdened growers. Farmers have become unsure of the future, especially regarding the produce and how the MSP (Minimum Support Price) will be impacted due to the entry of big players and whether the Government will continue to buy farm produce at the same price and quantity as before.

With the only means of voicing their concern being protests, the growers have of late tried to convey their feelings and insecurities regarding the Acts through demonstrations in Delhi, Punjab and other parts of the country. Sadly, their outcry has fallen on deaf ears till now. This muted response from the Government has now increased the farming community’s distress. This angst is expected to reach a crescendo in November when the agricultural community is planning to scale up the protests.

Already, the country’s farm sector is besieged by chronic problems such as mounting debt, poor quality seeds and overuse of pesticides besides the vagaries of the environment. However, being a hardy community and the spine of the Indian economy, the farmers have always fought their way through hurdles. The challenges thrown up by the environment in the form of rising temperatures and erratic rainfall, too, need to be met and responded to by the growers effectively and innovatively. The Government must enable farmers to deal with this instead of giving the impression of being callous about their welfare.

As politics rages over the Acts, worrisome developments are escaping the attention of policy-makers and the authorities concerned. A decade-wise observation of rainfall patterns shows that from October to December, rainfall has been at a record low of 100.06 mm for the 2010-2019 period as compared to 106.29 mm during the similar period in 2000-2010. The average post-monsoon rainfall has fallen below 110 mm. Coupled with this, droughts are getting more frequent and prolonged each year. Mid-2018 saw heatwaves fanning across India followed by scanty rainfall in the same year and in 2019 as well. These circumstances exacerbated the already daunting challenges for farmers, who had to bend over backwards to take the yield out of the parched land.

The adverse impact of the worsening environment on agriculture cannot be reversed overnight but the lot of the farmers cannot be allowed to deteriorate further as well. Therefore, there is an urgent need to innovate and evolve agricultural methods and initiatives that are capable of rescuing them from the grip of climate change. There is also a need to provide a sustainable solution that can be amplified across the sector on a large scale. An example of how this turnaround can be affected is available in a study published in the journal Earth System Science.

The research focussed on rice crops, which are the mainstay of South India’s agriculture. Rice also happens to be a major part of the diet of the southern population. The study concentrated on how the rise in temperatures, followed by scanty rainfall, was impacting the rice yield in Kerala, which was the chosen field of observation. The participants, who included experts from Japan, recommended altering the varieties of rice to a more heat-resistant strain that could withstand the fluctuating temperatures and yet be resilient enough to deliver an adequate crop yield. The experts also opined that the traditional sowing time needs to be shifted in consonance with the changing weather patterns so that the crop is in tandem with the weather trends. They recommended sowing at the end of July or the beginning of August in order to improve the quality of crop and provide ideal crop maturity time.

The study is an essential tool that provides baseline observations for ensuring future crop planning and maximising yield that accounts for climate variables, maximum and minimum temperatures, rainfall and solar radiation. The fact that the study was able to asses future crop yield projection amid constant carbon dioxide and meteorological values is crucial.

Furthermore, the tool of Growing Degree Days (GDD) incorporated into the study helped provide robust outcomes and observations. For the uninitiated, GDD is a measure to estimate the growth and development of plants in the growing season. The study was conducted using the CERES-Rice Cropping System Model.

The importance of agricultural adaptation to climate change in the current period cannot be stressed enough as food security and nutrition levels have been compromised exponentially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. India accounts for 17.7 per cent of the world’s population and a failure of the agricultural system in the form of yield and quality deterioration at this critical juncture can present a catastrophic scenario. The multiple challenges posed by the environment, policy issues and the long-standing systemic glitches can spell disaster for the agri sector. Unless the writing on the wall is understood and deciphered in time, India may be staring at a food crisis post the COVID-19 outbreak.

Food production is critical to keep the wheels of the economy turning. We mustn’t allow climate change to hijack our food security. This is only possible by being a step ahead of climate change complications.

(The writer is an environmental journalist)

Innovate for better results

by VK Bahuguna / 20 October 2020The Govt must take proactive steps to reform Indian agriculture to help production cross 500 million MT in the next two to three years

These days farmers across the country are agitating against the three farm Acts passed by the Government recently. If we analyse the status of agriculture today, we find that the sector is in dire need of innovation, both at the policy and ground level. Unless the Government deals with the real issues facing the farming community, nothing substantial will be achieved by simply reforming the existing structure that governs the sale and marketing of farm produce. Government officials and many in the public space think that the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) is doing a great job in declaring the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for a range of items like millet, pulses, oilseeds and so on, other than wheat and rice. However, the fact is that only six per cent of the farmers and only `2.5 lakh crore out of the `40 lakh crore total output from agriculture are covered by the MSP. From the point of view of food security, the MSP is an important intervention as it provides some financial security to the farmers and price stability to the consumers.

The main cause for concern is how to make farming profitable for the small and marginal growers who constitute 86 per cent of the farming community. They are neither able to invest in technology, better seeds and other inputs, nor in infrastructure. Most of them are at the mercy of the rain god who is now playing truant with them due to climate change, coupled with price instability and indebtedness. The rich farmers are able to manage somehow, but the poor get further indebted and trapped in bad loans.

Yet another problem is the reluctance of the younger generation to carry on subsistence farming. The Government must launch a climate adaptation site-specific programme for tackling the hydrology of the area to retain soil moisture. Increasing productivity is the only way we can double the farmers’ income. Take for example China. In 2010, it produced 500 million metric tonnes (MT) of grain from 143 million ha of net sown area. In India that year, this was only 240 million MT with the same sown area. Now with 140 million ha in 2020, we have inched closer to 300 million MT. Though the contribution of the farm sector in the GDP is around 17 per cent, it supports the livelihood of 58 per cent of the workforce of India. The Gross Value Added (GVA) by agriculture, forestry and fishing was estimated at `19.48 lakh crore in the current financial year (FY). The growth in GVA in agriculture and allied sectors stood at four per cent in the FY 2020-21. If the country wants to become a $5 trillion economy, we must lift the annual growth rate of agriculture by at least eight to 10 per cent in the next few years and then aim for more. This will require a concrete action plan.

As a first step, there should be planned networking to integrate land use with the adjoining forests through the creation of water bodies and implementation of watershed management schemes. This will help tackle climatic vagaries. The next approach is to opt for high value crop diversity for better production so that the return per unit of land used is enhanced. The farmers would require value addition and friendly market support. Though the Agriculture Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs) can no longer control the farmers, they can still be used for better procurement through the MSP and can become competitive with reforms in their functioning, specially by creating more facilities for the farmers in the context of the changed circumstances.

The Government should promote consortiums of investors and farmers while the small and marginal farmers should form cooperatives for negotiating with the sponsors for undertaking contract farming. In this venture, the APMC’s Mandi Samitis could also chip in to provide infrastructure and help. These cooperatives can create infrastructure and inputs for increasing productivity and help small farmers improve soil conditions and mitigate water scarcity through water harvesting. This will sort out the two major constraints in increasing production. Yet another help farmers need is to mitigate weather-related risks and for this, crop insurance policies must be made farmer-friendly. What do we do about the deteriorating soil health due to the overuse of pesticides and fertilisers? We must push for sustainable farming and the Centre and States must provide assistance to organic farming and conservation agriculture. As per the Compound Annual Growth Rate, the organic food segment is likely to grow from `2,700 crore in 2015 to `75,000 crore in 2025.

The Government must take proactive steps to reform Indian agriculture to help production cross 500 million MT in the next two to three years. Only then can the farmers’ income be doubled. The first thing to do is to open the door to agitating farmers. After all, it is they who have been feeding the nation.

(The writer is a former civil servant)

Farm reforms

by Sonal Shukla / 18 October 2020Instead of whipping up the esoteric phobia that the new farm laws will render APMCs redundant, the protesting State Governments should take this opportunity to make these sluggish bodies competitive for farmers by providing better services at lower prices

There are exigent issues in Indian agriculture. India, despite being the largest milk producer and second largest producer of food in the world, has just 2.3 per cent share in global export market, with low value addition. We process less than 10 per cent of agricultural produce and lose `90,000 crore rupees annually due to wastages. 44 per cent of Indian workforce is engaged in agriculture, contributing only 14 per cent to GDP keeping these people tied in very low-income traps.

India’s agricultural productivity is drastically low even as compared to global counterparts like BRICS; at Chinese yield levels, India could nearly double its production or halve the amount of land devoted to cultivation — freeing up that land for other purposes. So far, the Government’s strategy to help the farmers has been to provide subsidies, especially the MSP and input subsidies. However, only 6 per cent of the farmers have benefitted from the fruits of MSP, which mostly happen to be the big farmers; farmers from only few States like — Andhra Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana; and mainly for wheat and paddy. Another undesired offshoot of the MSP policy is the excess procurement of food grains by the Government — it has to procure 90 per cent of wheat from Punjab and Haryana — while 62,000 tonnes of food grains was damaged in FCI warehouses between 2011 and 2017.

At the time of independence, facing food deficit, we needed the targeted approach of MSP to increase the production of food grains. Currently, while having food surplus, we are suffering with the unsustainability of growing water intensive food crops at the lands ill-suited for them, owing also to free water and highly subsidised electricity, resulting in alarming fall of water table in certain States, especially Punjab and Haryana. If agriculture is to be made profitable, a focus on productivity increase, crop diversification, exports and food processing is essential, while creating infrastructure for minimising losses.

The productivity trap

The productivity difference between the rainfed agricultural area and irrigated lands is immense. Swaminathan Commission stated that 60 per cent of cropped area falls under rainfed agriculture contributing to only 45 per cent of total agricultural output. Thus, poverty is concentrated and food deprivation acute in this area. Agriculture is a very high-risk enterprise, much more so for small and marginal farmers which form 86 per cent of Indian farmer community and possess land holdings of less than 2 hectares. It is difficult to make agriculture profitable for them because they are too small for the use of modern implements, suffer from high input cost due to lack of economies of scale, leading to low productivity. Only 40 per cent of them manage access to formal credit, with low penetration of crop insurance. Thus, bearing the brunt of vagaries of nature as well as market volatility of food crops, stuck in the debt trap of money-lenders; these farmers are pushed to suicide. In 2019 alone, around 10,000 farmers and farm labourers died by suicide. The Ashok Dalwai Commission has also called productivity increase as the single most important factor in doubling the income of marginal farmer group.

Contract Farming and FPOs

In the recent policy initiative, the Government has adopted a two-pronged strategy: Contract farming and Farmer Producer Organisations (FPO). Contact farming will help the farmers, especially small and marginal farmers to access formal credit, modern implements, technical assistance, low cost inputs and assured price at the farm gate; thus, increasing crop productivity, avoiding wastage, shielding the farmer from pre and post-production risks. Another benefit of contract farming is selection of crops based on agro-climatic and soil condition of the area, making the agriculture sustainable.

FPOs are registered groups of local farmers — especially small and marginal ones — with a company like management structure. The function of FPOs is to help farmers in pre and post production operations from access to formal credit, inputs, technical assistance to primary processing, marketing, etc. They will also be well placed to negotiate over contract farming or private purchase of food produce with private players. They will be given monetary grant and credit guarantee by the Government to promote local produce. Government has also created Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF) of Rs 1 lakh crore for creating post-harvest infrastructure, which will be mostly functional by providing interest subvention on such projects; and the Government intends to utilise this Fund through the FPOs. It will have to be seen how much of this vision is actually implemented on the ground. The sustainability of the FPOs, post Government grant period, shall also be an area of concern.

State rights and APMCs

Allegations of encroachment of State rights and federalism are also being made as the Central Government used the entry 33 of the Concurrent List to bring out the farm Acts. It would be interesting to note that none other than Prof MS Swaminathan, the biggest well-wisher of farmers’ rights in India, had recommended shifting agriculture to the Concurrent List and creation of a single Indian agriculture market in his report in 2006.

While the APMCs were formed for fair and transparent price discovery for farmers, they have failed and succumbed to cartelisation, while becoming highly politicised. In return to the mandi fee, the services provided to the farmers are abysmal — with no cold storage facility, no facility for grading, sorting, packaging of food produce. Before the onset of e-NAM, the pan India e-trading portal by the Central Government, and push for mandis to connect — most weren’t providing e-trading facilities. Ashok Gulati, an agricultural expert, has placed an important question in the public domain: instead of fearing the redundancy of APMCs, why don’t the State Governments take this opportunity to make them a competitive option for farmers by providing better services at lower price? In fact, we are seeing a trend to that effect –Karnataka has greatly reduced the mandi fee; Punjab and Haryana have reduced the mandi fee for basmati by 50% or more. So, the future of APMCs is to become more efficient and effective and not be wrapped up, and States must work to that regard.

Farmers vs corporates

The reforms in agriculture have also created certain areas of potential hazard to farmer’s interests. As restriction for stocking up food is removed, it can lead to big retailers or corporates manipulate prices in the market, often to the disadvantage of the farmers. In contract farming also, corporates can dictate price to farmers and reject produce on the basis of quality, shape, size, colour, etc. Same fear of less negotiating power of farmers vis-à-vis big buyers, during sale of food produce even outside APMC, exists.

Create Market Regulator

While capitalism has taught the world that competition improves quality of options, we are equally aware of tendencies of monopolies forming without any active oversight of State, rendering the competition neither free nor fair. Hence, an independent market regulator and dispute redressal forum (akin to TRAI and TDSAT) must be created for agricultural sector to check unfair practices by corporates and private players and protect the interests of farmers.

Further, if the farmers are to be truly free and agriculture to be made profitable and sustainable — there’s still no alternative to Government’s own work on the front of setting up cold chain for farmers in villages, implementing more irrigation projects, recharging of aquifers, greater push to extension services and primary processing at farms.

(The author is a public policy analyst and a lawyer, an alumnus of National Law University, Jodhpur)

Consensus is vital

by Priyadarshi Dutta / 13 October 2020Had the Government chosen a Standing Committee scrutiny or even had a dialogue with farmers, the opposition to farm laws could have been avoided

The new farm laws might not be as disruptive as their critics want us to believe. They are apparently as logical and timely reforms as interventions like State procurement and notifying of Minimum Support Price (MSP) had been in the mid-1960s. The ruling and Opposition parties are engaged in a wholly avoidable fracas, both refusing to view things in totality. The Opposition is indulging in loathing and fear-mongering, reminiscent of the times when economic liberalisation was introduced in 1991. Paradoxically, it was the Congress’ Government then. The party now is behaving differently when in the Opposition.

The Government’s cavalier attitude to the Opposition parties’ stance is equally uncharitable. Motives have been imputed to their decision. They are accused of having a vested interest in the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC)-run mandis, besides being friendly towards the middlemen who call the shots in those market yards. Ironically, on the National Agriculture Market portal (eNAM), started by the present Government in 2016, there were no less than 83, 958 commission agents registered as on August 31. Why is the Government promoting middlemen here?

The fear that APMC-run mandis would be abolished is largely unfounded. The eNAM platform can today boast of connecting about a 1,000 of them across 18 States and three Union Territories (UT). However, the passage of the Bills was not preceded by any kind of consensus-building. There was no dialogue with the farmers’ unions, State Governments or the Opposition parties. The laws were rushed through the Ordinance route on June 5. This starkly contrasts with the spirit of federalism and the consensus model that marked the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The matters concerned with agriculture being under the State list in Schedule VII of the Constitution called for Centre-State consensus.

The legislative competence of Parliament to discuss a Bill on a subject placed in the State list (Schedule VII of the Constitution) was questioned by some members. However, we have precedence of the Seeds Act, 1966, which is a Central legislation. It was one of the key legislations enacted during the Green Revolution era. Still, one is reminded of how the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Government approached the contentious subject of contract farming. This was envisaged in the National Agriculture Policy 2000. Instead of bringing a Central law, the Government in 2003 circulated a Model Agricultural Produce Marketing (Regulation) Act to the States for adoption in 2003. The ensuing UPA-I Government continued the policy. Contract farming was included as an option in the National Farmers Policy (2007). By August 2007, a total of 15 States had brought amendments in the APMC (Regulation) Acts based on the model legislation.

Why did the four Labour Codes, recently enacted, did not become a source of dispute despite the presence of controversial provisions? This was because the Codes, meant to reduce 29 existing labour laws into four legislations, were vetted by the department-related Standing Committee of the Lok Sabha. It was chaired by Bhartruhari Mahtab of Biju Janata Dal. The Government agreed to several suggestions of the committee.

How justified is the claim that previous governments had kept the farmers in chains? Such a view stems from inadequate appreciation of facts. Definite pro-farmer measures were taken by Indian National Congress since 1937 when it formed governments in coalition in seven out of 11 provinces (under Government of India Act 1935). These included debt relief measures, tenancy reforms and licencing and regulation of money lenders and so on. But separation from Burma (now Myanmar) from the Indian Union in 1937 stressed rice availability in India.

India’s agricultural policy since Independence was aimed at attaining food security. With fragmented landholdings, inadequate electricity supply, pitiable irrigation facilities and poor acreage, production was insufficient. To bridge the requirement and availability of food grains, India entered into an agreement with the US under their Public Law 480 on August 29, 1956. It allowed India to obtain wheat, rice, cotton, dairy products and tobacco in Indian rupees. It could not, however, be denied that import of food grains, in excess of the market requirement, de-incentivised the farmer to produce more. The production increased as the imports were brought down to realistic levels around 1966. However, the completion of the Bhakra-Nangal Dam on Beas-Sutlej (1963) was an achievement of the Jawaharlal Nehru Government, which accelerated the advent of the Green Revolution.

The current regime of MSP and Government procurement is a legacy of the short-lived Lal Bahadur Shastri Government (June 11, 1964 to January 10, 1966). It had its origin in the decline in wheat production, consecutively between 1962 to 1964, and decline and marginal recovery of rice production during the corresponding period. This compelled the Government to revisit its open market policy for wheat and modest control on transport and sale of rice. The severity of the food shortage could be understood from the sheer number of speeches that Shastri delivered on the subject as the Prime Minister. His Selected Speeches, published by the Publications Division, Ministry of I&B (1972) categorises a total of 10 under “Food Problems.”

The Shastri Government moved in towards a regime of greater regulation and control on sale, purchase and movement of food grains. On January 1, 1965, two new organisations were created, which became the hallmark of the Government’s intervention in the agricultural sector. These were Food Corporation of India (FCI) and Agricultural Prices Commission (now Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices). The ambit of Government procurement, which was limited to a few edible items in the beginning, now extends to 23 items (in addition to sugarcane).

The developments since the Green Revolution (1967) have led to the growth in acreage and food surplus situation. Time is ripe for addressing the neglected problem of agricultural marketing. In pursuit of doubling the farmers’ income by 2022 (from the level of 2016), the Narendra Modi Government formed a committee led by Ashok Dalwai, IAS. The committee produced a 14-volume eminently readable report. Though the decision to “liberalise” the farm was not among its direct recommendations, one has to realise that significant decisions are always political rather than bureaucratic in nature. The farmers must have better alternatives for remunerative pricing with legal safeguards. Even today, there is no legal restriction on farmers selling his/her product in the open market. What cripples the farmer, however, is not merely the logistical problem but also the absence of a legal architecture to protect his/her interests.

A single line in these Acts, like “notwithstanding anything contained in the aforesaid sections, no trade transactions should take place below the notified MSP”, would have allayed the misgivings of the farmers. A line in time could have saved the Government from putting eight Cabinet Ministers on ground (not including the Agriculture and Farmer Welfare Minister Narendra Singh Tomar) to convince agitating agriculturists.

(The writer is an author and independent researcher based in New Delhi. The views expressed here are personal)

Farmers’ own middlemen

by Moin Qazi / 09 October 2020Growers can empower themselves through a livelihood strategy that collectivises the smaller producers into FPOs which are then integrated into an inclusive value chain

Three new farm Acts were recently introduced in the country. The most important of these, the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 is aimed at putting an end to the monopoly of the Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) mandis. Earlier, under the 1964 APMC Act, all the farmers were required to sell their produce at the Government-regulated mandis. The arhatiya (middlemen) in such cases helped the farmers in selling their crops to private companies or Government agencies. While APMCs will continue to function, farmers will now have a wider choice. But one of the powerful ways that growers can serve as their own middlemen is through a livelihood and development strategy that collectivises the smaller primary producers into locally-managed Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) which are then integrated into an inclusive value chain. This is a sustainable, market-based approach in which resources of member farmers (for example, expertise and capital) are pooled to achieve more together than they can individually. It enables members see their work through an entrepreneurial lens and confers economies of scale, better marketing and distribution, more investable funds and skills, greater bargaining power, access to credit and insurance, sharing of assets and costs, opportunities to upgrade skills and technology and a safety net in times of distress. The best-known example of an FPO is that of Amul (Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd), which is a dairy cooperative with over three million producer members.

In this model, thousands of scattered small farms are systematically aggregated and provided centralised services around production, post-harvest and marketing. This helps reduce transaction costs of the farms for approaching value chains and makes it easier for small farmers to access inputs, technology and the market. It also opens opportunities to bring primary processing facilities closer to the farm gates and helps producers gather market intelligence and manage the value chain better with digital agriculture tools. An FPO is a hybrid between a private limited company and a cooperative society. Hence one can see it enjoy the benefits of professional management of a private limited company as well as reap the benefits of a cooperative society.

Small-holder farmer producer groups are a key medium to build scale on account of the confidence, support and buyer/seller power they provide. They are able to achieve economies of scale through post- harvest infrastructure (collection, sorting, grading facilities), establishment of integrated processing units, refrigerated transportation, pre-cooling or cold stores chambers, branding, labelling and packaging, aggregation and transportation, assaying, preconditioning, grading, standardising and other interventions. The key benefit is the marketing support that links producers to mainstream markets through aggregation of subsistence-level produce into economic lots that can significantly raise the share that peasants get from the money people pay for their food.

The FPOs are owned and governed by shareholder farmers and administered by professional managers. They adopt all the good principles of cooperatives, the efficient business practices of companies and seek to address the inadequacies of the cooperative structure. The best way for these organisations is to leverage their collective strength through a full value chain from the farm to the fork. The underlying principle is similar to that of the full stack approach. This approach makes the sponsor, catalyst or promoter responsible for every part of the experience. In short, it is a whole-farm systems approach. It creates a complementary support ecosystem that boosts farm yields, reduces negative environmental impacts and increases market access and small-holder farmer incomes. It also provides sustainability interventions, including sustainable irrigation products and practices. Moreover, the value chain uses a business approach in order to make it viable.

Apart from the collective strength that group synergy generates, the support structures help in building the capacities of producers to deal with input suppliers, buyers, bankers, technical service providers, development-promoting agencies and the Government (for their entitlements), among others. One of the FPO’s important roles is linking farmers to reliable and affordable sources of financing in the funding ecosystem to meet their working capital, infrastructure, development and other needs. The collective works to reorient the enabling environment by influencing policies in this direction. The extension services available through the collectives include augmenting farmer capacity through agricultural best practices, agronomic advice, training on use of bio-fertiliser, pest management, modern harvesting techniques and access to optimal environmental practices. The success of a collective hinges on many factors: The technical support it receives, its institutional base, social and professional composition, land access and cropping patterns of members and adaptation of the model to the local context.

Sadly, rich farmers are significantly more likely to participate than the less privileged. They often become administrative members and use services substantially more for themselves than for rank-and-file members. It is, thus, necessary to strengthen democratic processes in these institutions.

Most promoters of the value chain are now successfully using the sub-sector approach, which allows for a focus on specific sub-sectors and helps in strengthening the ecosystem within which they are able to transition from a comparative to a competitive advantage. The value chain also facilitates capacity building support and use of modern tools including technology that can help to improve weather forecasting, agricultural processing, soil health monitoring crop identification as well as damage control, and mapping of available water resources. Some of these collectives are using digital tools to make farming climate-resilient, nutrition-sensitive and inclusive. The farmers are also able to achieve increase in the quantity, quality and consistency of production of crops. For achieving better scale, the value chain needs to steward limited resources and build production systems that natural systems can support over time. This logic embraces the use of soil management regimes that incorporate modest, targeted use of synthetic fertilisers to boost farmer incomes and production without affecting the quality of soil. The technical support is complemented by better water management through rain water harvesting and recharging of the ground water table; introduction of multi-cropping and diverse agro-based activities; use of low-cost and small plot irrigation technologies, which are commercially viable and environment-friendly. There is also a need for a policy to pool land or increase the size of holdings through collective farming or some other way. Consolidation of small-holders’ land holdings through cooperatives can also create synergies, especially for the leasing of large equipment or bulk input orders. It helps in creating cold storage for controlling post-harvest losses. Financing for setting up micro-irrigation facilities and rainwater harvesting modules would help create an infrastructure for sustainable water supply and hence aid farm productivity.

FPOs should also be encouraged to participate in Minimum Support Price-based procurement operations. The eNAM platform can connect farmers with distant buyers. However, the biggest limitation of eNAM and other similar programmes seems to be that the vast majority of farmers are not tech-savvy. This is further compounded by low internet penetration and erratic electric supply. We need robust farmer-producer institutions which will have capital and the risk-taking ability to set up processing zones which are critical for preventing losses on account of rotting foodgrains. Together with FPOs, farmers can be their own middlemen and India can finally see the dream of farmers’ incomes being doubled being realised.

(The writer is a well known development professional)

Acts of growth, empowerment

by Vijay Bahadur Pathak / 06 October 2020The Opposition is staging protests against the recent farm reforms though the measures contained in the three Acts will enable barrier-free trade in agricultural produce and empower farmers to engage with investors of their choice. These Acts, which are a bid by the Centre to empower growers and double their income by 2022, will free them from unnecessary legislation, bring fundamental changes, give impetus to investment and increase employment in the agriculture sector, which in turn will strengthen the economy of the country. The promotion of contract farming will help farmers reach an agreement with food processing units/exporters on an individual or organised basis. It will also enable them to reduce the input of fertilisers and seeds, reduce other costs and use modern techniques to maximise products and get a better market as they will have the opportunity to work according to national-international demands.

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act seeks to create an ecosystem where the farmers and traders enjoy the freedom of choice relating to sale and purchase of produce. This facilitates remunerative prices through competitive alternative trading channels to promote efficient, transparent and barrier-free inter and intra-State trade. This was proposed because there were restrictions to selling agri-produce outside the notified Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC). And growers could sell the produce only to registered licensees of the State Governments. This legislation will open more choices for farmers, reduce marketing costs and get them better prices. It will also help growers of regions with surplus produce to get better prices and consumers of regions with shortages, lower prices. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Act seeks to provide for a national framework on agreements that empowers growers to engage with agri-business firms, processors, wholesalers, exporters or large retailers for services and sale of future produce at a mutually agreed remunerative price framework, in a fair and transparent manner.

This has been done because agriculture is characterised by fragmentation due to small holding sizes in India and has certain weaknesses such as weather dependence, production uncertainties and market unpredictability. This makes it risky and inefficient in respect of both, input and output management. Now the risk of market unpredictability will be transferred from the grower to the sponsor. Farmers have been given adequate protection and an effective dispute resolution mechanism has been provided with clear redressal timelines.

The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act seeks to remove commodities like cereals, pulses, oilseeds, edible oils, onion and potatoes from the list of essential commodities. This will remove fears of private investors of excessive regulatory interference in their business operations. The freedom to produce, hold, move, distribute and supply will lead to harnessing of economies of scale and attract private sector/Foreign Direct Investment. Farmers suffer huge losses when there are bumper harvests, especially of perishable commodities and this Act will help drive up investment in cold storages and modernisation of the food supply chain.

The Opposition parties have Governments in different States and they should show what they have done for the farming community. Take the case of Uttar Pradesh (UP) which is striving hard to double the income of farmers. During the lockdown, the Yogi Adityanath Government exempted 45 items of fruits and vegetables from mandi fee, which benefited growers who are now free to sell their produce anywhere in UP. They also have the option to sell their goods in the mandis where only one per cent user charge is taken from traders. Besides, all 119 sugar mills of UP ran at full capacity and produced 126.36 MT of sugar after crushing 1,118 lakh tonnes of sugarcane. As a bumper kharif crop is expected, the Mandi Parishad and the State Warehousing Corporation are building warehouses of 5,000 MT capacity each in 37 mandis. Farmers can keep their produce here free of charge for 30 days, after which they will get 30 per cent rebate on the rent, so that they can sell their products when they get the best price. The UP Government has ensured that the produce will be recognised as a guarantee for the farmers to get bank loans.

UP is developing 27 modern Kisan Mandis and in 24 of these, cold chamber and ripening facilities for preservation of fruits and vegetables are being made. This project will have a ripening chamber of 20 MT capacity and a cold chamber of 10 MT capacity. It is expected to be completed by 2020-21. Also, during the lockdown, 35.77 lakh tonnes of wheat was purchased, as were pulses and oilseed and it was ensured that the market price should be at least at par or above the Minimum Support Price. Now efforts are afoot to purchase paddy, pulses and oilseeds at the MSP in order to benefit farmers.

(The writer is a member, Legislative Council of Uttar Pradesh and vice-president of UP BJP)

New agricultural paradigm

by Sandhya Jain / 30 September 2020The end of socialist-era impediments should ideally stimulate increased private sector investment across the value chain and help create jobs

The over-hyped green revolution of the late 1960s introduced varieties of dwarf rice and wheat in northern India with a cocktail of chemical fertilisers and pesticides that sucked up groundwater and gradually made it unfit for drinking. The chemicals leached into the soil and water. State-sponsored propaganda about “miraculous yields” extended the phenomenon across the country, ruining soil fertility and the nutritious value of food crops; the impact on public health was noticed by the medical community but all voices were silenced. Today, Gurdaspur-to-Delhi trains are called “Cancer Express”, yet there has been no medical study of the harm caused by chemical agriculture to the health of humans, animals, soil and water resources.

Now, four momentous laws could pave the way for a revolution in which farmers drive the change, with technology playing a supportive role. If the Government repudiates the genetically-modified food crops lobby, India could return to farming methods that do not require costly inputs and force farmers into a vicious cycle of debt (and even suicide).

On September 16, 2020, one day before the three agriculture-related Bills were moved in Parliament, the Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2020 was passed, bringing all cooperative banks under the purview of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). It means stricter supervision of 1,482 urban and 58 multi-state cooperative banks, with deposits of Rs 4.84 lakh crore.

The legislation undermines the strongmen who control the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs), mandis, loans and so on in many States. It is noteworthy that large farmers are resisting the new laws; earlier they opposed the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (MGNREGA) as they had to match wages or lose farm labour. The ongoing COVID pandemic has also improved the bargaining power of farm labourers and added to the bitterness of large farmers.

Often, agents arranged debt-funding for farmers from private moneylenders, who charged usurious interest and enjoyed political heft; such debt has been linked to farmer suicides in some States.

Simultaneously, the Union Cabinet approved the Rs 15,000 crore fund for animal husbandry as part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan stimulus package and a scheme for interest subvention of two per cent to “shishu” loan category borrowers for one year under the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana. These developments form the sub-text of the farm Bills.

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act 2020 allows sale and marketing of produce outside notified APMC mandis. State Governments cannot collect market fee, cess or levy for trade outside the APMC markets; inter-state trade barriers are nixed and provisions have been made for electronic trading of agricultural produce. No licence is needed; anyone with a PAN card can buy directly from farmers. The new system provides a dispute resolution mechanism in case farmers are not paid immediately or within three days.

The APMCs failed as they allowed vested interests to seize the system. States levied cess to earn extra revenue that was not part of the budget and was used for “discretionary” development spending, mostly under the Chief Minister’s orders. As the cess increased, political appointees took charge of the APMCs. Even the Food Corporation of India (FCI) paid cess. Small farmers were burdened with the cost of transport to take their produce to the mandis and deal with middlemen. For instance, waiting outside sugar mills, with heat evaporating the sugar content in the cane, desperate farmers have succumbed to agents (of nearby mandis) who arrive miraculously and dictate the price.

Under the new Act, politicians and urban elite farmers will find it difficult to get large “agricultural” incomes mandi-certified and pay zero per cent income tax, as payments have to be made against PAN cards.

The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 regulates contractual farming rules and State APMC Acts. Farmers can make contracts with a corporate entity or wholesaler at a mutually agreed price. The system already exists in 20 States; PepsiCo buys potatoes from 24,000 farmers across nine States. Further, 18 States already permit private mandis while Kerala and Bihar don’t have APMC mandis at all. More pertinently, the Act prohibits acquiring ownership rights of farmers’ land.

The Centre has funded Rs 6,685 crore for the formation of 10,000 Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and the Rs 1 lakh crore Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF). The FPO will give farmers higher bargaining power while AIF and market reforms serve as additional enablers. They can invest in farm equipment, infrastructure and build forward market linkages by making agreements with agribusinesses, thus improving access to technology and investment. Maharashtra’s Sahyadri Farmers Producer Co. Ltd, with 8,000 marginal farmers, exports 16,000 tonnes of grapes every season.

The end of socialist-era impediments should stimulate increased private sector investment across the value chain, creating jobs in logistics service providers, warehouse operators and processing unit staff. The rise of food-processing industries could create non-farm jobs in rural areas.

India processes less than 10 per cent of output (cereals, fruits, vegetables, fish, etc) and loses around Rs 90,000 crore annually to wastage. Hopefully, market linkages will motivate farmers to diversify and grow crops such as edible oils and help reduce India’s edible oil import bill that currently stands at over $10 billion.

Finally, The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 removes excessive control on production, storage, movement and distribution of food commodities; removes cereals, pulses, oilseeds, edible oils, onion and potatoes from the list of essential commodities, and paves the way for cold chain infrastructure to come up. Previously, control regarding the storage of essential commodities (onions, potatoes, edible oils, jute, rice paddy, sugar) gave draconian powers to authorities to raid “hoarders”, confiscate stocks, cancel licensing and even imprison offenders. This naturally discouraged investment in storage as entrepreneurs feared being prosecuted as “hoarders.” Lack of storage also contributed to volatility in prices as their stability depends on adequate warehousing infrastructure.

Henceforth, the ECA 2020 will be invoked only under extraordinary circumstances such as war, famine, natural calamity of grave nature and extraordinary price rise (100 per cent increase in retail price of horticultural produce over the preceding 12 months, or 50 per cent increase in retail price of non-perishables over the preceding five years).

Dismissing the propaganda that the new laws would end the minimum support price (MSP), the Centre has quietly ordered procurement, effectively nipping the canard that small and marginal farmers would be short-changed. Implementation will be the key.

(The author is a senior journalist. Views are personal)

Free market or Company Raj?

by Indra Shekhar Singh / 28 September 2020Corporations and agro-processors can demand graded products for MSP. Otherwise they may not buy at all or at reduced prices. Where will the small farmer go then?

A Bharat bandh, millions of farmers on the streets, eight Opposition leaders suspended, National Democratic Alliance (NDA) partners and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) affiliates openly rebelling against the Government, these scenes have been dominating our news cycles. Yet Prime Minister Narendra Modi is confident that the three farm Bills are good for India.

Theoretically, the Bills appear well-intentioned but the devil is always in the implementation. Overall, they aim to empower farmers to sell from farm-gate but in the process end up empowering corporations and traders to expand their businesses and swamp the farm to fork chain. A new wave of liberalisation just rammed into rural India. But many suspect the real agenda is generating “agri-dollars” and in the words of dissenting (Telangana Rashtra Samithi) MP Dr Keshava Rao, to “make an agriculture country into a corporate country.”

The Government argues that farmers are not free to sell anywhere because of a “corrupt and middlemen-infested Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC).” Hence, break the APMC and free the farmers. Now corporations and any other person with a PAN card can directly procure products from farmers. Agri-business companies can enter into contracts with them. But what complicated matters was the lack of substance in the Bills, no mention of a guaranteed price for farm pick-ups in case of a bad year or excess yields and the Government’s cavalier manner of handling the Rajya Sabha last Sunday, negating debate and passing the Bills by voice vote. This naturally raised more doubts. Indian farmers have had centuries of slavery under the Company Raj and perhaps that’s why a muffled voice of MP SR Balasubramaniam, who evoked the “Champaran Satyagraha”, rang the loudest. APMC will be replaced by the corporate market as there is no fair agreement between two unequal parties, he stated. He may be right after all as a David and Goliath can never have a fair agreement. Neither can sheep and wolves co-operate, nor can a corporation and a marginal Gond farmer in Madhya Pradesh.

Today the farmer is weak, highly indebted and trapped in the cycle of over-production and low income. His monthly household surplus is under `1,500 per month. This has already been destroyed by COVID-19. Each harvest season, his input and production costs rise, yet he cannot even sell at a minimum support price (MSP). As per reports, only six per cent farmers sell at MSP, the remaining 94 per cent are dependent on markets and traders outside the APMC mandi. Reality check — small and marginal farmers cannot even reach the APMC as they don’t have any means of transportation, forget selling outside their geographic limits. The majority of farmers are marginal. This means they only grow enough to feed their families and sell a little surplus to the markets. From the village field, away from the town, they sometimes find it convenient to sell to local traders.

Most of them begin the sowing season by taking credit for seeds and fertilisers and repay them through post-harvest sales. The tenant farmers are worse off. They want to sell at MSP but due to the trader-creditor-farmer relationship and market forces, which have an upper hand in price fixation, they cannot.So, on the face of it, liberalisation seems to be a good step as “farmers can sell anywhere.” But is it? Here we must go by the warning given by MP Professor Manoj Jha to the Rajya Sabha: “You have replaced the rohu and hilsa with the sharks. You will bring the East India Company back to India.” He was referring to traders as the small fish and the big agri-business corporations as “sharks” that have no personal connection with farmers. In fact, most farmers still trust their eco-system of licenced commission agents as they deliver on prices and guarantee sales.

Given agri-dollars in their pockets and new reform policies, food majors can break any market and create monopolies, forcing the farmers to sell cheaper or let their produce rot. Not convinced? Let’s go back to the dal scam of 2015. After an investigation by the IT department, a scam valued at `2.5 lakh crore was unearthed. The consumers paid the price by buying arhar dal at `210/kg. It was reported that a cartel of agri-business companies was responsible for buying pulses at low prices through the supply chain networks and hoarding it overseas, creating artificial scarcity and profiting immensely by selling the stocks back to Indians at high prices. The Government used the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) to bust hoarders and recovered 75,000 metric tonnes of dal. But now, even the ECA limits on hoarding and stocking are being done away with.In 2006, Bihar removed the APMC regime and the real incomes of farmers in the State have fallen while private investment is yet to move into the State. Only traders are carting produce from Bihar all the way to Punjab to sell in mandis.

Many vouch for APMC reforms and not its destruction as the regulated market is still the farmer’s best chance at getting MSP. This is evidenced by Punjab. Won’t rural India be engulfed by corporate markets that will ruin APMC systems and farmers’ rights as the growers will be left unprotected overnight without a transitional and transparent system codified? The Samajwadi Party MP, Professor Ram Gopal Yadav, asked if these reforms can assure the farmers’ good prices? No, because the difference between APMC and corporate markets would be of “BSNL and Jio”, he said. It was Biju Janata Dal MP, Dr Amar Patnaik, who had first warned against “cartelisation.” In effect, the private sector will be a phoenix rising from the ashes of our public infrastructure.

The biggest problem in procurement, as we have seen globally, is grading. Corporations and agro-processors can demand graded products for MSP and if the gunny bag is ungraded, they may not buy at all, or at a reduced price. This is common practice, which results in huge losses for farmers and food security of the world. Traditionally traders graded the produce. With them gone, will farmers bear grading costs? Naturally, if they do, MSP can never be realised.

There are also serious questions on post-harvest infrastructure and warehousing in rural India. Will the farmers, due to bad storage facilities, make distress sales? The new reforms favour the big farmers and agri-businesses but are detrimental for small and marginal farms (below two hectares) that constitute 86.21 per cent of our total land holdings.

Further, once the market forces evolve, unless MSP is made a legal right or Government procurement increases, achieving it will be a challenge. Contract farming is specious. A glimpse into the US model is enough to deduce how the contracting parties (agri-business firms) force the farmers to buy their recommended seeds, fertilisers and other inputs, often from their allied stores or vendors and at their prices. They also force the farmers to buy more equipment, increasing the cost of production each year. If the farmers don’t abide, they don’t buy the produce and legal proceedings follow.

In India, the poultry sector is a good example of how the owners have been reduced to farm hands on their own property. And to take two steps back, PepsiCo filed a case against Gujarat farmers unfairly. PepisCo has got more flak as many potato farmers committed suicide due to their procurement policies in West Bengal. The stories of contract used to exploit farmers are endless. The next big problem is no small and marginal farmer has access to the Sub-Divisional Magistrate and District Magistrate. How many of them will be able to go to the already over-burdened official to settle trade disputes? Even their journey for justice will become a nightmare given their literacy levels and manipulation by the bigger parties. The companies or traders will not be criminally liable; this is a regressive step favouring big agri-businesses.

Modi needs to critically think about rising farmer suicides and doubling farmers’ income by 2022. He ought to dispel the farmers’ doubts and insist on specifics and mechanisms like ensuring the retail buyers do not go beneath a cut-off price. Otherwise, the haze of silence can be ominous . One fears the day when the words of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) MP TKS Elangovan come true — “To sell the farmers themselves as slaves to the big industrial houses… It will kill the farmers and make them a commodity.”

(The writer is programme director for policy and outreach, National Seed Association of India)

Bills to grow farmers’ income

by Bindu Dalmia / 28 September 2020Reforms will have a net positive impact as the agricultural sector moves from a subsidy-centric to a market-oriented approach, encouraging the agripreneurial aspirations of the growers

Tough times are testing the most resilient of leaders globally. Despite the nation being confronted with serial adversities, Modi 2.0 retains and compounds the Prime Minister’s political capital by powering on with the reforms agenda, regardless of the clamour by “compulsive contrarians”, as the late Arun Jaitley referred to the Opposition.

Since the lockdown, the Centre has pressed ahead with a series of incremental reforms: From the Atmanirbharta series to the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and the trilogy of agriculture reforms. Then there are the three new Bills intended to consolidate social security for migrant labourers, which will impact 80 per cent of the population employed in the informal sector. The series of post-pandemic legislations cannot be viewed in silos but must be seen as a set of structural and incremental reforms aimed at rebooting the economy and improving the ease of doing business (EODB) for farmers.

The post-Corona “new normal” challenges every vector of economic growth to optimise and converge resource efficiencies. This is so that each vertical of the economy turns self-sustaining and profitable. Agriculture is one vertical that has been constantly dependent on subsidies, doles and welfarism. This has been a constant drain on the exchequer as it was compelled to fund an uneconomic sector. To make matters worse, the farm sector delivered only subsistence-level earnings to the farmers, a point validated by the NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) estimates which show that rural indebtedness escalated by 12 per cent between 1993 to 2013.

Mitigating agrarian distress requires reducing dependency on cultivation as a source of livelihood and moving towards value-added manufacturing. Because, a whopping 58 per cent of our workforce is dependent on farm income, but contributes only 17 per cent to India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). At present, agriculture can only deliver a growth rate of 3.4 per cent per annum, whereas we need the sector to increase its productivity potential to at least 10 per cent in order to lift rural India out of poverty. Increasing per capita earnings can only happen through expansion of economic activity by firing equally on all four cylinders of the economy: Agriculture, manufacturing, exports and services.

Essentially, the intent of any reform must be gauged by the “degree of inclusivity embedded in its blueprint.” Considering that 500 million of our workforce is engaged in farming, the landmark reforms will have a net positive impact as the agricultural sector moves from a subsidy-centric to a market-oriented approach, encouraging the agripreneurial aspirations of the growers.

The agri-reforms, though politically sensitive, were much needed after 73 years of Independence in order to transit towards a “One Nation, One Market.” Each farm Bill enables this transition differently. But this article specifically focusses on the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020, which will increase efficiencies in the low-profit agriculture sector by opening it up to contract farming.

Why is corporatising agriculture a farmer-friendly reform? India, having matured to a food-surplus economy, is today more in need of focussing on “surplus-management” to decrease wastage. This will increase farmers’ profitability by ramping up cold storage facilities and food-processing infrastructure that will lead to value-added manufacturing. The annual agri-wastage is estimated at `92,000 crore, so corporatisation of the sector will enable building a seamless farm-to-consumer supply chain.

Contrary to allegations that the legislation is loaded in favour of corporates, I wish to substantiate through empirical evidence how corporatising the sector benefited farmers. It profited growers by underwriting their seasonal produce through a negotiated pre-fixed price with corporates that offered income surety. It also encouraged a shift from mono-cropping to crop diversification, bought in new technologies and helped in financing and modernisation. The best Indian examples of corporatising farming are seen from the outcomes of the Amul paradigm, the e-chaupals and the Patanjali models of sourcing from farmers’ collectives.

The active involvement of farmers in shared initiatives creates a sense of co-ownership as seen in the successful prototype of the Amul cooperative which was legendary in leading the White Revolution. Today, India is the largest milk producer, and Amul is the largest food product FMCG outfit with a `52,000 crore turnover. The winning philosophy of Amul’s strategy was that it treated the dairy farmer as a stakeholder by offering him higher prices for the produce while purchasing, yet sold it to the consumers at marginal profits.

I am guilty of being politically incorrect by validating another example on how pursuing a successful Chinese template can benefit India, too. In 2016, the State Council of China officially made rural e-commerce a national strategy in its anti-poverty drive, which decreased poverty rates from 10.2 per cent to 1.7 per cent in the last six years. And one of the ways it achieved this was by uplinking farmers onto Alibaba’s e-commerce platforms of the Taobao Village.

The Bill on contract farming is a win-win for both suppliers and marketers. The collectives gain by tapping into multiple synergies derived from the corporates’ ability to support post-harvest logistics, processing, packaging, branding, retailing and their access to a wide distribution network. Marginal and small farmers own less than five hectares of land, so when they form collectives, the aggregation favours regular income, and, in fact, serves to enhance their collective economic and bargaining power.

Narendra Modi had promised to double farmers’ income by 2022. The status quo in their earnings will remain if this incremental reform is not translated into action. The challenge is doubling farmers’ income without unduly raising consumer prices, even as input costs continuously increase. To boost profitability, farmers need the skill sets at the command of corporates who have deeper insights into the ever-changing consumer needs.

To cater to the altered behavioural profile of the post-contagion consumers mean that they now have diminished purchasing power, yet seek superior nutritional benefits, better hygiene and contactless doorstep delivery. Also, the share of cereals in middle-income households is reducing in favour of fruits, vegetables and milk. Demand for value-added processed foods is on the rise. Increasing health and wellness awareness, too, is generating demand for a wider variety of foodgrains. This calls for a fundamental transformation for the farmer, from selling whatever was his traditional produce to adapting to what the consumer actually wants.

When demand-driven value chains enter the sector, they bring enormous benefits to the growers as they are able to align production with market demands. Because, at the end of the day, increased crop productivity alone is not sufficient to raise farmer incomes if market needs do not support such production.

Eventually, the Centre must aim at building consensus by assuaging apprehensions of farmers, who are being misled through fear-mongering by vested interests, lest they succeed in sabotaging a progressive legislation, as in the case of aborting the Land Acquisition Bill. Though agriculture is not in the Concurrent List and remains a State subject, as the new laws deal with inter-State trade, it becomes a Central subject. This should hold up to legal scrutiny. The Centre is then well within its rights to enact laws and no State Government that challenged this provision has won in the past.

Besides, over time, once farming turns into a lucrative industry, it holds the potential of widening the taxpayer base and could then be considered for being transferred to the Union list. The Centre should in fact aim at taxing farmers thus far exempt from taxation. Especially the rich growers with over 10 acres of land. A fair yardstick of evaluating taxation herein would be to take three-year averages, as there are annual variations in produce due to climate-risks.

Ultimately, India must harness the potential to transform into a mega food processing hub by optimising efficiencies, as the farmer, too, aspires to move up in Masclow’s hierarchy of needs and go beyond the Congress era slogan of “roti, kapra aur makaan (food, clothing and housing)” to partake in a thriving modern economy.

(The writer is author, columnist and Chairperson of the National Committee for Financial Inclusion at the Niti Aayog.)

Opp conundrum

by Opinion Express / 24 September 2020The unity in the House, for once, was admirable but without a sustained campaign on the ground, visuals are futile

In the end, a moral victory is inconsequential, simply because it doesn’t change the facts on the ground. As noted American satirist HL Mencken said, “In human history, a moral victory is always a disaster, for it debauches and degrades both the victor and the vanquished.” So though, for once, the Opposition seemed to have got its way in meeting the President over the farm Bills and was united against the Government’s gross subversion of parliamentary procedures in rushing through them in the Rajya Sabha by a voice vote despite lacking the numbers, what stops the new laws? The President is not likely to withhold assent or send the Bills back except granting an audience. Even if he were to do so hypothetically, they would be passed again, with or without any amendments, as the ruling BJP has an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha and has already set a precedent of passing debatable Bills by voice vote without discussion, deliberation or consensus. Besides, the President is not bound to act within a time-frame. And the way more Bills were passed even as the entire Opposition stayed away from the House in protest, it looks like the ruling party has no compunction in reducing an august institution to a stamping authority. So Opposition members can speak and cry hoarse all they want but cannot seek solace in parliamentary procedure or vetting by committees to stop motivated laws from being enacted. And when it comes to street fights, last year’s general elections showed us how the members of the grand anti-BJP alliance frittered away their best intentions to their selfish, regional interests. Till that cohesiveness congeals as a single movement, there cannot be any hope for the Opposition.

Worryingly, the Upper House passed three key labour reform bills that ought to have been discussed and debated given their sensitive nature. The Government has enough numbers in the Lok Sabha to override dialogue and even if outnumbered in the Rajya Sabha, it knows it can hijack debate by provoking the Opposition enough and use a voice vote in the resultant din. Or simply take advantage of a boycott. The three Bills relate to new labour codes on industrial relations, social security and occupational safety, all in the name of easing business while diluting workers’ rights. Nobody expects the Government to be unreasonably welfarist but in a post-pandemic economy that has witnessed record joblessness, it allows companies with up to 300 workers to fire staff without government permission. The Government, however, feels that this would actually encourage employers to hire more than the previous limit of 100 and, in fact, create jobs. But employers in stressed times are hardly expected to be altruistic and given that our unorganised labourers comprise a big chunk of the country’s workforce, they continue to be exposed to vagaries of market forces. The Rajya Sabha also passed the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, which ostensibly provides a framework under which organisations in India can receive and utilise grants from foreign sources. This is an umbrella watch on what is unsuitable to this Government the most, namely NGOs, research organisations, think tanks and civil society activists. And the carefully enunciated regulatory mechanism envisaged by the Bill, of course, remains vague about the conditions under which it can be used, lumping them as anything that is detrimental to “national interest.” Nobody denies the need for greater transparency when it comes to activities sponsored by foreign sources but would that also be used to vet the PM Cares Fund, which is currently exempted under FCRA, or selectively be applied to “anti-national” NGOs? Or does the Government believe that NGOs shouldn’t exist to point out gaps in its policies and implementation? Besides, most of these organisations have a high record of tax compliances over the years but by making Aadhar and SBI bank accounts mandatory for receipts, the Bill implies tighter controls and increased transaction costs, which are meant to create more impediments. This is just a way to stifle and discourage independent voices than a clean-up as is being proposed. It is the same kind of doublespeak that is latent in the farm Bills. On the face of it, they look reformist, dismantling the heavily cartelised Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) and middlemen, and allowing farmers freedom of movement and trade. Question is some of them do not have the investable resources or the expertise for an outreach beyond their geographic limits and would have to depend on “traders” or the corporations. The smaller and marginal farmers are not literate or educated enough and would not be able to counter the heft of corporations in negotiations and price fixing. In that sense, they could still end up being exploited as before. The farmers fear that in an open, competitive market, they would not get the minimum support price (MSP) that the Government promises to continue and given the diversity and multiplicity of markets, the guaranteed official procurement would be hit over time. Besides, nowhere do the Bills insist on the MSP as a criterion of farm pick-ups by “traders” and “sponsors.” They would, therefore, still be in crisis and at the mercy of the dictates of marketers. Besides, the proposed laws are still vague on defining the mechanisms that would replace the regulated economy. This kind of obfuscation has become so familiar that it is in danger of becoming the norm than the exception. And without Question Hour in Parliament, it’s time the questions are asked on the streets. The farmers’ ire may just be the beginning of the next electoral plank.

(Courtesy: The Pioneer)

FREE Download

OPINION EXPRESS MAGAZINE

Offer of the Month