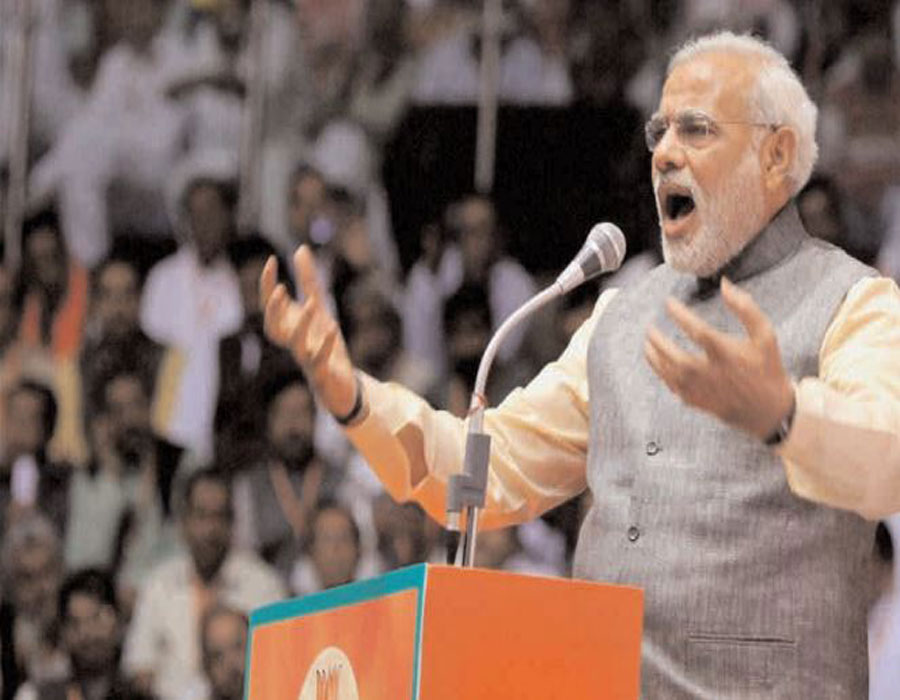

A person becomes hope for millions, certainly Narender Modi must be complimented for the extraordinary achievement. India is a continent, it is not a country. Over billion people are living in India hence to be the hope of India is huge responsibility. The elevation of Narendra Modi through popular demand has democratized the Bharatiya Janata Party. From a patriarchal system where the elders of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and of the party decided things, Modi has forcibly brought in elements of an open system where merit and democratic appeal inside the party will determine its direction. Such a takeover of a major political party by an individual purely on his credentials and popularity has no precedent in India.

In the two decades from the formation of the party to the time that it took power in the late 1990s, the BJP was controlled by only two very competent presidents - Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani (with one short term for Murli Manohar Joshi). When the party formed the government in Delhi and both Vajpayee and Advani held ministerial responsibility, the party presidency was finally let go of by them.

In this period, to communicate the idea of an open democratic system that was unlike the closed dynastic system of the Congress, BJP presidents continued to be elected. But because the rivalry was strong between Vajpayee and Advani, this president was a safe person, meaning someone neutral, and with no base of his own. And so the BJP had presidents like Kushabhau Thakre, Jana Krishnamurthy, Bangaru Laxman and Venkaiah Naidu. They were picked through consensus between the rivals, not through competitive elections, meaning the system was actually closed and not open. The cadre did not have a say in the choice of their leader.

These men did not make any changes or define a new direction for the party, and they were not supposed to. They were placeholders, and held office till the big boys came back to play. The important aspect is that because the system was closed, no new leadership actually emerged in the BJP through the popular route.

The disappearance from public life of Vajpayee after his defeat in 2004 and the eclipse of Advani within the party (about which more later) after his defeat in 2009 exposed this vacuum and opened up the space for someone to take the national leadership. It was assumed that this would be someone from inside the closed system. The BJP had some leaders who were "national", like Sushma Swaraj, Pramod Mahajan and Arun Jaitley, groomed for bigger things, and some who were "regional" like Modi and other state chief ministers.

This division did not indicate true levels of power. Jaitley for instance has never contested an election and has no popular appeal. Advani's visit to Pakistan in 2005 and his concession to Jinnah put off a cadre that craved someone who would take them back to first principles, meaning the muscular Hindutva that had propelled it to power.

This is when Modi emerged as his own man. A confluence of things - first, the killings of 2002 and the proven involvement of his ministers (one of who has been convicted), second, his no-nonsense image and refusal to play by the rules of inclusive secularism, such as wearing skull-caps and hosting iftaars, and third, his competent man-aging of Gujarat's economy and the praise of corporate leaders - has made him a national figure.

He attracted the core BJP worker and voter because of the first two things, and also large parts of the middle class. The media, which is usually wary of communal politics, has been neutralised through the third aspect, corporate endorsement of Modi.

The selection/election of Modi as the head of the party's campaign for 2014 has actually made him more powerful within the party than its president, Rajnath Singh, because it reveals him as the popular choice within the party. Modi gives the lower rungs of the BJP and the RSS what they want, a full-throated and uncompromisingly Hindu nationalist leadership which radiates strength and power. Even if Modi per-forms poorly in the election of 2014, he will retain control of the BJP. This is because his power comes directly from the cadre of both the BJP and the RSS, and the groundswell has opened up the closed system. or Narendra Modi's supporters there is nothing beyond the 2014 elections. So every alliance bro-ken, every leader brushed aside and every political leader who criticises is meant to be set aside as the Gujarat Chief Minister's campaign machinery rolls on towards the 2014 polls. But are the numbers against him?

In an excellent analysis of the 'Modi phenomenon' in India in the Indian Express, Ashutosh Varshney notes that the Gujarat Chief Minister would need to be a trailblazer of sorts rarely seen in India before and maybe his supporters and BJP are being a bit too hopeful of an impending victory in 2014. He points out that the BJP has seen its vote share decline over the last three elections to 18.8 percent, and though the party can hope for 18 to 20 percent of the vote share to get to 180 seats, a more practical assumption would be that Modi needs to raise the party's vote share by 5 to 6 percentage points. What is that in numbers assuming an electorate of 800 million votes in the 2014 polls? 25 to 30 million votes.

It isn't impossible to raise one's vote share by that much, and Varshney points to three instances when it happened: in 1984 for the Congress after Indira Gandhi's assassination, in 1991 for the BJP over the Ayodhya temple issue and in 1998 for the BJP, because of allies who delivered the numbers. There is a strong anti-incumbency wave among the electorate against the Congress and the UPA but would it be one that would result in 25 million votes going in Modi's favour? Varshney, maybe rightly, points out that it is unlikely given the Gujarat Chief Minister's personality cult is one that is still resonates only with urban voters. He says:

First, beyond Gujarat, the rural folk, who still determine India's election results, have not heard of the Gujarat model. And it is virtually impossible to turn rural constituencies around in a matter of months. It is a longer political project. Second, it is also not clear that, beyond Gujarat, the urban poor share the urban middle class passion for Modi. And the numbers of the urban poor are substantial. Third, in southern and eastern India, even in cities, the BJP's presence is minimal.

While Varshney finds fault with the numbers against Modi, in an editorial in the Hindu, Harish Khare finds more wrong with the personality cult of the Gujarat Chief Minister, something he claims the BJP has tried to ride on in the past and failed. Pointing to the sup-port of the cadre in favour of the Gujarat Chief Minister, he says:

Mr. Modi is equally entitled to his personality cult. But make no mistake. Mr. Modi is a different personality, not easily amenable to democratic moderation. We should get used to "Rambo" type yarns, as the polity seeks to rede-fine itself in the next general election.

Khare says that the Gujarat Chief Minister may seek to harness the strong anti-incumbency but warns that the drowning voices of dissent against anything anti-Modi doesn't augur well for the democracy that is India.

The liberal perception and numbers may be against the Gujarat Chief Minister and it may explain why the BJP 2014 campaign chief is urging his party members to find allies quickly to create the numbers the party needs to come to power. The Gujarat Chief Minister may also, in some corner, be willing to play along with alliance politics to forgo the Prime Minister's chair for a later innings in 2019 or after. The question is, will his supporters be able to wait?

Narender Modi is trying to model himself on Syama Prasad Mookerjee, he was both a liberal and a nationalist. While much of his politics and time in Government reflected deep nationalism and a realism free of dogma, at his heart were core liberal principles. Reading through the biography written by Madhok one can trace the roots of his liberal nationalism all the way to his days as the Vice Chancellor of Calcutta University in the 1930s at a very young age of 33.

Recounting a convocation address by Mookerjee on February 12, 1936, Madhok cites the following excerpt from that speech which highlights the Liberal Nationalist that Mookerjee was:

"Our ideal is to provide extensive facilities for education from the lowest grade to the highest to mould our educational purpose and to draw out the best qualities that be hidden in our youth and to train them intellectually physically for service in all spheres of national activitty in towns villages cities. Our ideal is to make the widest provision for sound liberal education… Our ideal is to make our universities and educational institutions the home of liberty, sane progressive thought."

One sees the same spirit of Liberal Nationalism emerge through his tenure as Vice Chancellor as he sought to expand access to the University even to who were not enrolled in a regular college. A focus on youth and grooming of the next generation is a recurrent theme in his liberal nationalism.

"I have abundant faith in the glory of youth … they be given a chance to live, an opportunity to enjoy life and the amplest facilities for the development of their health and character."

One also sees during his tenure as the Vice Chancellor an ethic of minimum government. He did not depend on Government or wait for Government to create opportunities for youth. He proactively introduced many measures like abolishing reserved hostels and messes and expanding the curriculum to include sciences and engineering. He was also opposed to the idea of putting limits on higher education to control the number of graduates on the lookout for employment.

Delhi intellectuals fear coming of no-nonsense Modi Syama Prasad Mookerjee's liberal nationalism is evident through his years with the Hindu Mahasabha during the independence struggle as well. In a speech in December 1943, making the case for the Hindu Mahasabha, Mookerjee explains that he stood for no special favours for Hindus but for welfare and advancement of India as a whole. The cynical politics of wordplay on "secularism/communalism" of the Congress predates India's independence. Even an intellectual of Mookerjee's stature was not spared the game of labeling that we continue to see even today.

Many examples of Mookerjee's liber-al nationalism can be found through Balraj Madhok's book. In a speech in 1943 in Amritsar to the Hindu Mahasabha, Mookerjee spoke of how an Idea of India that transcended both caste and religion and that called for political citizenship to everyone without discrimination. In the years after Independence when he was invited to join Nehru's Cabinet as the Minister for Industries, one sees his economic liberalism grounded in the realities of India come through very clearly. Madhok writes:

"He had very clear ideas on the role of private capital in the industrial development of the country as also on the relationship between capital and labour… He was for giving full scope to private enterprise under suitable Government regulation … He wanted government to concentrate its meagre resources on the defence of the realm … he stood for a rational coordination between private and public capital in light of the actual conditions in the country…"

In Balraj Madhok's eyes, Mookerjee a was realist who was not guided by dogma. Citing two examples of how he believed in private enterprise while being pragmatic about economic realities of India, Madhok explains how Mookerjee was opposed to full nationalisation and that he did not believe India had the skills resources to nationalise and run all kinds of industries. At the same time, he also believed that given the realities of labour in India, that there had to be some kind of profit sharing between capital and labour. While investing in public sector enterprises, he also believed that needed professional management independent of Government to make them viable and keep them efficient.

Over the years, after he resigned from Nehru's Cabinet and quit the Hindu Mahasabha before eventually founding the Jan Sangh the liberal national ethic travelled with him. His inaugural presidential address to the Jan Sangh once again sees the same ethic of economic liberalism:

"we stand for well planned decentralized national economy….. against concentration of economic power in cartels…. sanctity of private property will be observed….private enterprise will be given a fair and adequate play….state ownership and state control only where it is needed in public interest….progressive decontrol…"

The issue that saw him most rile up Nehru in Parliament was the Kashmir issue. On this too his position was a liberal national position.

"Kashmir is an integral part of India and should be treated as any other State"

It is a reflection of the perversity that has afflicted much of the intellectual discourse in India that an issue like the demand for abrogation of Article 370, far from being labelled as the liberal national issue that it ought to be, is dismissed as a 'communal' issue or even worse described as a 'Hindutva' issue.

While Mookerjee's political legacy will be coloured by the leftist historians with all kinds of labels, it would be instructive to point out that he commanded even the respect of the Communists through his defence of civil liberties and his opposition to the Preventive Detention Act.

This comment by Mookerjee in response to Nehru's repeated labelling of him as 'communal' brings out the best in him:

"If we try to recover our lost position in a manner 100 per cent consistent with the dynamic principles of Hinduism for which Swami Vivekanand stood, I am proud to be a communalist."

By marking the soft start to what will be deemed to be the campaign for the next Lok Sabha in Madhopur, Narendra Modi will be laying claim to that political legacy of liberal nationalism that Mookerjee stood for many decades back when he founded the Jan Sangh to challenge the Nehru-led Congress's political monopoly in India. All the contentious issues namely Ayodhya Ram temple, abolishing article 370, uniform civil code are delibretely untouched by team Modi to build up international acceptance but the pressure from the cadre and right wing forces within core group of the party will be just waiting to pounce on Modi to express his opinion in public to polarise votes for BJP.

By Prakhar Prakash Mishra, Political Editor

OpinionExpress.In

OpinionExpress.In

Comments (0)